As Levi Martin reflects on the Nuu-chah-nulth language, he rejects the notion that it is endangered.

Despite being one of an estimated 10 remaining fluent speakers within his nation, the Tla-o-qui-aht elder describes it as a “language in hiding.”

As a young boy, he absorbed his ancestral tongue during story time on his father’s lap.

Hours would pass them by as they sat on the edge of the Pacific Ocean in the tiny village of Opitsaht. Distracted only by the faint hum of a fishing boat drifting by, or a sea lion coming up for air, Martin can still remember his father’s teachings with precision.

Everything changed when he was taken away to Christie Residential School on Meares Island.

Before he left, his father presented him with a bag of medicine that he kept tied around his neck as protection, “because he knew he wasn’t going to be there to look after me,” he said.

Martin arrived at the school not knowing a word of English. On the very first day of school he was strapped across his hands by his supervisor, who called himself a “brother,” for speaking his language. It was the only time that Martin received a beating. It was also one of the last times the then seven-year-old spoke his language at the school.

When Martin returned home for the summer, he showed off the English he learned to his parents with pride.

His mother quickly pulled him aside and said that he was not to speak “a white man’s language,” because he “wasn’t a white man.”

Although he continued to speak Nuu-chah-nulth with his family during the summer months, the Catholic Church was eventually victorious in their efforts to shame Martin out of speaking his ancestral tongue.

Once he began high school at St. Mary’s Indian Residential School in Mission - nearly 350 kilometers away from his family - he stopped speaking the Tla-o-qui-aht dialect altogether.

It’s a story that repeats itself throughout the homes of Nuu-chah-nulth families up and down the west coast.

For many fluent speakers, their language was something they kept hidden within themselves to safeguard their loved ones.

“Because the Catholic Church tried to beat it out of us, my own way of protecting my kids was not to teach them our language,” said Moses Martin, Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation’s elected chief. “I never taught any of them.”

As a result, only 108 fluent speakers remain within the 12 Nuu-chah-nulth nations surveyed in the 2018 Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages.

B.C. accounts for around 60 per cent of the First Nations languages in Canada. There are currently 34 Indigenous languages within the province. Of those, three per cent of the reported First Nations population are fluent.

Almost two decades passed before Martin was reintroduced to his language at a Round Lake treatment centre for alcoholism when he was 36. While participating in a sweat lodge ceremony for the first time, he was stirred by messages from his ancestors. Sitting on the cool earth as heat from the fiery coals flushed through his body, everything his parents taught him in Nuu-chah-nulth as a child started rushing back.

“One of the messages I got said I needed to go back home to work with the people,” Martin recounted. “To reconnect the people to the land, language and spiritual ceremonies.”

After spending more than half his life suppressing his ancestral teachings, Martin was moved to reawaken their sleeping language.

He spent a year preparing for his move back home after leaving the treatment centre in 1981. In Opitsaht, Martin began working with elders in his community to create audio recordings of songs as a teaching tool.

“Language is a connection that we have to our ancestors,” he said. “It comes from the ancestors and we’ve held on to it. Now, we’ve got to pass it on to our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.”

Sonya Bird is an associate professor of linguistics at the University of Victoria whose research focuses on pronunciation in the context of Indigenous language revitalization. While B.C. is incredibly rich in terms of linguistic diversity, she said we are at a “critical time” to create audio recordings and written documents.

“Many of the languages are spoken as first languages by a very small handful of elders and those elders are passing on,” she said. “If language revitalization efforts don’t happen now, within the next decade or two, we’ll have lost a lot of those elders and knowledge keepers.”

In 2003, FirstVoices was developed by the First People’s Cultural Council (FPCC) to support Indigenous people engage in language archiving, teaching and cultural revitalization. The web-based suite of tools allows nations to create their own language sites by uploading words, phrases, songs and stories as audio and video files. Now, 32 out of the 34 First Nation languages in B.C. can be found on the platform.

“It’s simply imperative to reconciliation in our country that we provide resources and opportunities for [First Nations communities] to have self-determined language projects,” said Kyra Fortier, language technology programs coordinator for the First Peoples’ Cultural Council.

Ehattesaht, Nuchatlaht, Hesquiaht, Tseshaht, Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' and Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations have all created language sites for their own respective dialects on FirstVoices. FPCC supports data sovereignty by ensuring the communities themselves maintain the ownership and management of the resources they place on their sites.

Traditionally an oral language, the shift to document language through audio and video recordings has only recently been more widely adopted.

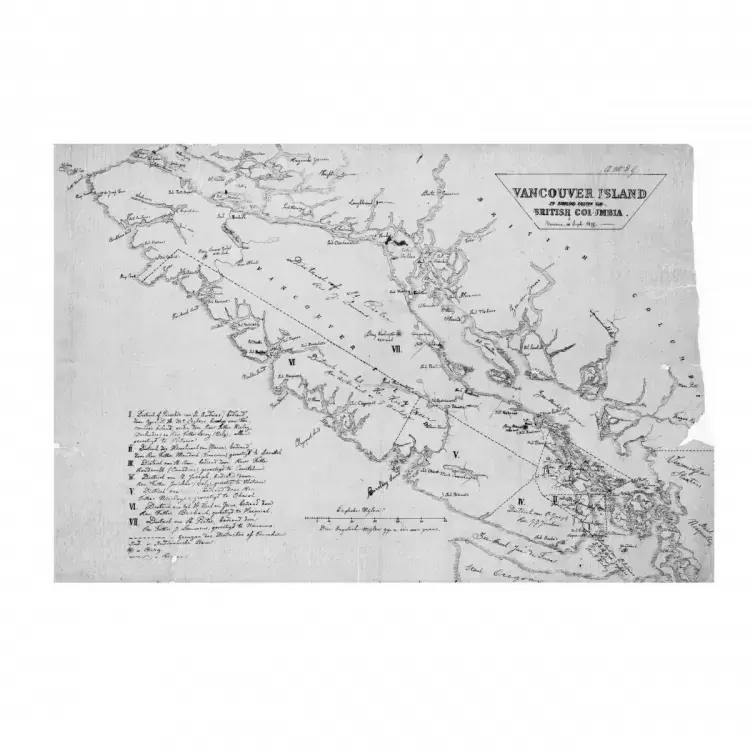

“Historically, linguistics in B.C. was originally started by pioneers and missionaries,” said Fortier. “Their purpose in taking down linguistic information was to translate religious texts, ultimately, as a tool of colonization.”

While documentation by settlers has formed the foundation of a lot of language revitalization resources, Bird said it’s important that the work is now being led and directed by the communities themselves.

Examples of self-determined language programs can be found throughout many Nuu-chah-nulth nations.

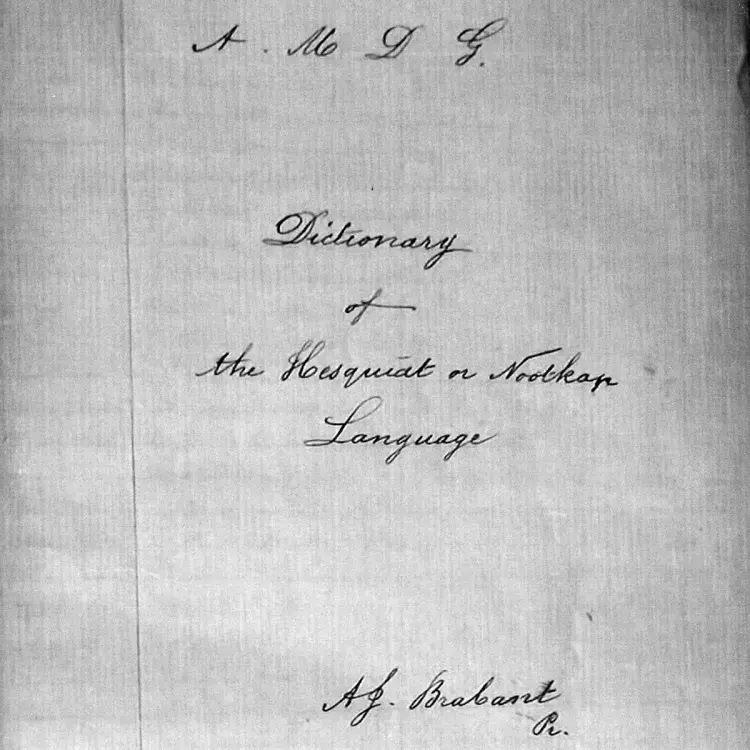

As part of the Hesquiaht Language Program, a handwritten dictionary by Reverend Auguste Joseph Brabrant in 1911 was transcribed into the nuučaan̓uł phonetic alphabet by the late-Larry Paul, Angela Galligos and Layla Rorick.

Rorick, who coordinates Hesquiaht’s language program, said that Brabrant wrote the dictionary so someone could replace him as a missionary in Hesquiaht.

“He asked different elders in the community to confirm meanings and didn’t credit anybody –that continues today,” she said. “We understand that we know what we know because we are in relationship and connection with everybody in our community.”

Rorick has been meeting with nine of the nation’s 12 fluent elders every week since 2014. In June they began teaching an online language program that has attracted nearly 100 students, ranging from Vancouver Island to California and beyond.

“The language is coming back from the effort of the group,” said Rorick. “Everyone remembers different things and [collectively], they put a more together a more complete picture of the use of our language. Nobody is bringing the language back themselves as an individual – it’s the whole group. All of our fluent speakers are bringing it back for people.”

Pat Charleson is one of the nine elders involved with the Hesquiaht Language Program. The 90-year-old was hesitant to begin with, feeling apprehensive that younger generations wouldn’t be interested in learning.

“But, by golly, I feel good about it now,” he said. “There’s so many wanting to learn … us elders, we don’t know when we’re going. It could be tomorrow, or next week.”

When he is no longer able to, Charleson said he hopes Rorick will carry the language forward.

“It would be a great legacy for her if she carries it on,” he said. “You lose a language, you lose a culture.”

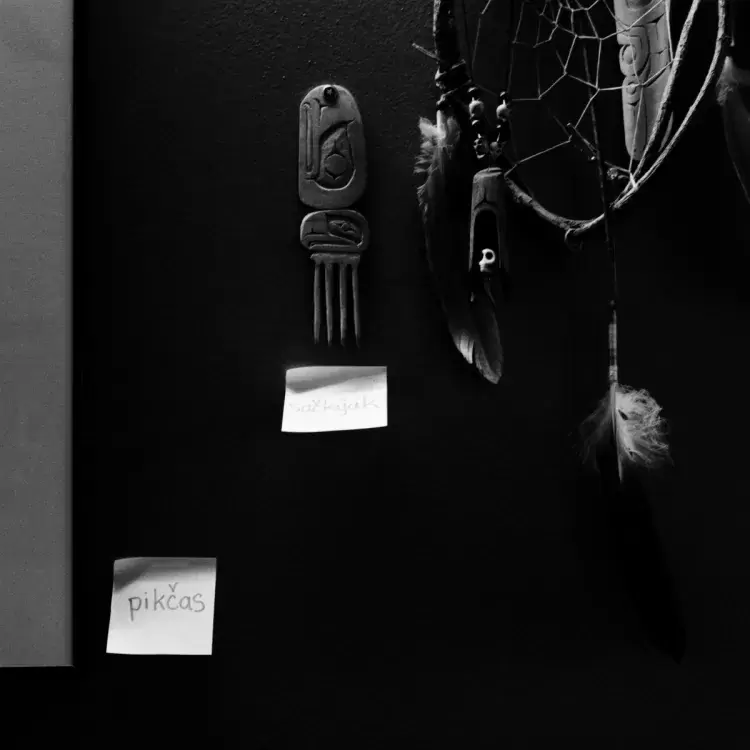

For Rorick, speaking her ancestral tongue is an act of defiance.

“We’re responding to the damage of colonialism by speaking our language in our homes,” she said. “We’re also creating a whole different environment for our young ones.”

For years, Levi Martin’s granddaughter Gisele tried learning her language before getting discouraged and giving up. It wasn’t until 2010 that she earnestly started investing her time and energy into studying. Levi Martin’s language class was what propelled her forward, she said.

Since Levi moved back to the west coast in ’81, he’s used language as a bridge to help his community connect with their ancestors.

“It gives me a better understanding of our teachings,” he said. “It’s a connection to my ancestors and a connection to the future.”

Through a mentor-apprentice program, Gisele spent 900 hours in language immersion with Martin over three years which “catapulted” her learning.

“Nuu-chah-nulth is an ecologically based language,” she said. “Our language has come from this place – from the plants, the animals, the sound of the land...it feels like a cosmic spiritual language in the ways that concepts, ideas and sentences are put together. It’s entirely different and beautiful.”

When Levi first started teaching languages classes in 2000, he said that there would only be five people that would last the 12-week program. Now, the 75-year-old is seeing anywhere from 15 to 20 in a class.

As younger generations tussle with how to make the guttural sounds that form some of the Nuu-chah-nulth words, the language is morphing.

“Like all cultures, languages change over time,” said Levi.

Rorick recognizes the shift but said it only fuels her desire to carry it forward.

“If we continue our efforts, we will definitely get closer to [where] we want to go,” she said. “Even if it takes more than our lifetime, it’s worthwhile.”

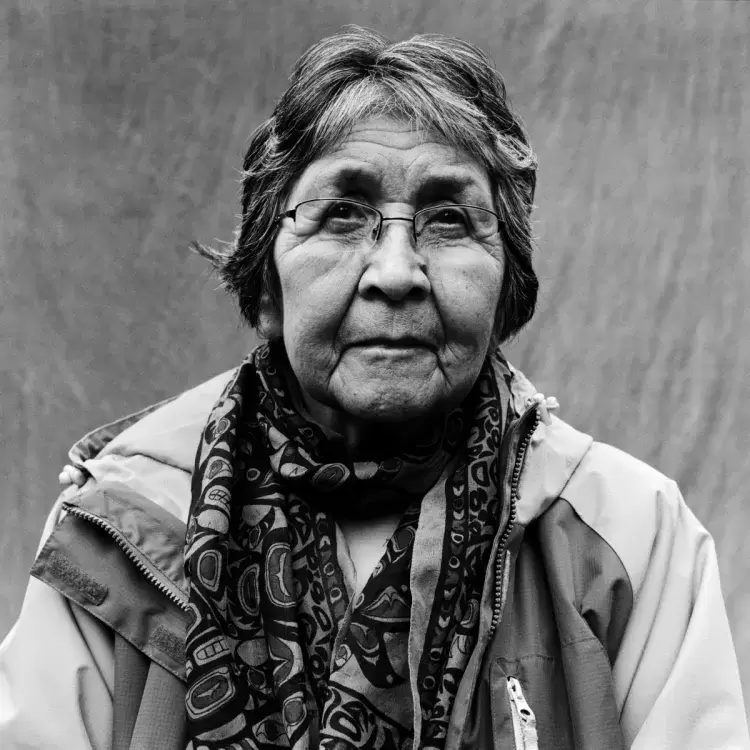

Helen Dick grew up in a fluent speaking home and continues to speak her language fluently. "I used to hear my mom tell us, 'just be who you are. Don't let people try to change who you are or what you are. You be you.' So that's how I've tried to live my life," said the Tseshaht elder, on Jan. 20, 2021.

Moses Martin, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation elected chief, is one of the remaining fluent speakers within his nation. The 79-year-old said he is helping to generate audio recordings "for future generations." "There's so much to our language that it changes your whole way of thinking," he said. "It was dying but it's not too late. It's something that we can bring back," on Jan. 17, 2021.

Pat Charleson is one of the nine elders who participates in the Hesquiaht Language Program. As a boy, the 90-year-old remembers listening to his father and the elders speaking their language. "I understood all the words they were saying," he said. "I really never lost it – it was all in my head." The Hesquiaht elder met late-wife, Mamie, at Christy Residential School. They went on to have 15 children together. Now, Charleson has 53 grandchildren, 106 great-grandchildren and 40 great-great-grandchildren.

Frances Tate was born and raised near Nitinaht Lake. The 77-year-old was raised in a fluent household but lost much of her language while attending residential school. In her late-50's, she began taking language classes through the Ditidaht Community School. She now identifies as semi-fluent. She helps children with the pronunciation of words and phrases at the school. "Some of our elders say that [our language] is very close to being extinct – it’s very close to being gone," she said.

Benson Nookemis did not know a word of English when he was sent to the Alberni Indian Residential School. His mother hardly knew any English so he was raised speaking the Huu-ay-aht dialect, which he continues to speak today. The 85-year-old said he can count the remaining fluent speakers within his community on one hand. "It makes me feel sad," he said. "We're losing our language."

Barney Williams is one of the remaining fluent speakers within the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation. He attributes the decline of fluent speakers to the residential schools' "shame-based way of teaching." "We carried that trauma through life," he said. "We were always afraid that if we talked, we'd punished, or that somebody would laugh [at us]," he said, on Jan. 20, 2021.

![Levi Martin wears a shawl that he dons while delivering ceremonies on big occasions. "When I have to speak in public, I the ability to connect with the ancestors," he said. "I will be their voice [to] channel their message," on Jan. 16, 2021.](/sites/default/files/styles/news_node/public/photos/Elders9.JPG.webp?itok=yCbMG4nU)