Representatives of Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations have been meeting regularly over the last few weeks to come to grips with the enormous federal funding reduction facing the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council; a whopping 60 per cent cut as prescribed by a new national funding formula announced Sept. 4 by Minister John Duncan of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.

The cut—$750,000 of the current $1.24 million in NTC core funding—came as a shock to the tribal council (NTC), which had been in negotiations with Aboriginal Affairs Canada on a new five-year funding agreement.

NTC had been advised in writing, even as late as July 26 of this year, that Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council funding would continue as per the current five-year agreement that is set to expire at the end of March 2013. The federal negotiators in this region too were caught off guard by the minister’s announcement, made via a press release out of Ottawa.

The cost of these funding cuts in human terms is significant to an organization that provides more than 50 distinct ongoing services to its 10,000 Nuu-chah-nulth citizens on behalf of their respective First Nations, with many other short-term service agreements being fulfilled as well.

Currently NTC employs 154 full-time equivalent staff. The promised cuts will have a potential direct impact on 25 of those jobs, and will have many more indirect impacts.

Tribal Council core funding is used to operate such areas as the capital projects department, administration department, communications department, leadership, and finance department.

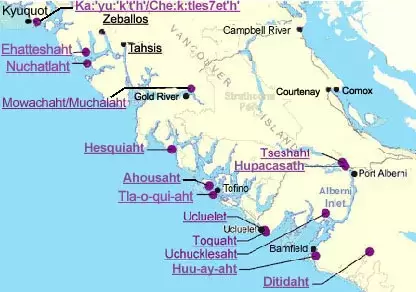

The Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, made up of 14 individual nations located along the remote and rugged West Coast of Vancouver Island, has used the ‘economies of scale’ approach to maximize both efficiency and effectiveness in its operations, bringing communities much needed and varied services that would otherwise be unaffordable to already overburdened individual First Nation budgets.

Take as an example of that the Capital Project Advisor Services provided to the nations by the tribal council. This department currently employs one staffer shared among 14 nations. It provides advice on capital projects large and small, like the construction of the Big House for Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nations near Gold River, the dock and renovations of the community centre at Ocluje for Nuchatlaht, or the state-of-the-art geo-thermal power plant for Tla-o-qui-aht. New schools, new subdivisions, health centres and current First Nations capital asset upgrades all benefit from this staffer’s sage advice and trusted support on everything from trades selection, tendering processes, funding reporting requirements, grant applications, construction standards, building scheduling and financial management.

This service reduces the need for individual remote nations to hire costly consultants for their construction projects. It guards against the self-interested, the incompetent, or those who would take advantage of nations who have neither the capacity nor the in-house knowledge to make informed decision on highly-technical matters.

This service, valued by Nuu-chah-nulth nations, is in danger of being lost because of the new government “formula” that caps tribal council funding at $500,000, regardless of the number and scope of the services being offered.

The formula offers three tiers for funding tribal councils. NTC falls into tier three of the formula as it has one or more of the following characteristics: serves an on-reserve population over 5,500; or serves nine or more member First Nations; or delivers six or more major AANDC programs.

The “formula” refuses to acknowledge the geographic challenges of the tribal council service area. Many of the communities that are serviced by NTC are located along remote logging trails or accessible only by boat or float plane. These are communities that already face less service than others in Canada. Now, Canada’s Government threatens the services they are receiving by decreasing the capacity of the expert organization delivering them.

When asked about the cuts on Nov. 13, Dr. James Lunney, MP for Nanaimo-Alberni, said he was not consulted about the funding cuts nor the tiered funding program established by the government to cap tribal council funding at a maximum of $500,000. He said however that there had been significant investment in the region by the federal government over recent years. He cited the Tseshaht Administration Building as one such investment, as well as the Ty-histanis subdivision for Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, and the high school at Ahousaht.

Lunney said all areas of government have been asked to tighten their belts. He said it was regrettable that good people and programs may be lost in the process, but it was his hope that individual nations would pick up the services that the tribal council would no longer be able to provide. When asked if that meant more money would go to the nations to provide these services, Lunney told Ha-Shilth-Sa he was not prepared to speak about the issue.

At the foundation of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s success is its finance department. Canada’s Government over recent years has placed an ever-increasing burden on First Nations communities in their reporting requirements, and the tribal council works to ensure member nations have the tools and support they need to keep communities viable.

With this new funding formula, Canada’s Government is shifting the focus of tribal councils away from this kind of advisory service. Aboriginal Affairs has said First Nations should instead rely on the services of organizations such as the Aboriginal Financial Officers’ Association for advisory services. (In response, the AFOA stated on Sept. 12, that it is not in the business of providing financial advisory services at any level.)

Consultation and fiscal management support for first nations that require help in this area can run as high as $1,000 a day. Any savings to Aboriginal Affairs’ bottom line through cuts to tribal council funding are downloaded directly onto the backs of individual communities and their members.

Another curious thing about this new funding formula is that it flies in the face of what the tribal council has already achieved. With this new funding formula, Canada’s Government promises multi-year funding agreements with minimum two-year terms. But Canada’s Government has long-since acknowledged NTC’s successful fiscal track record. While many tribal councils are challenged by year-to-year funding arrangements with government, NTC is entering its seventh five-year funding agreement, which speaks to the confidence government has had in NTC’s fiscal management. The variety of programs and services NTC has been able to attract and deliver to Nuu-chah-nulth people is a direct result of NTC’s solid track record in this regard.

Canada’s Government says its goal with this new funding formula is the “efficient and effective delivery of essential programs and services.” This is what NTC has already achieved in this remote area of Canada. Yet instead of supporting NTC’s efforts, Canada’s Government, through the ministry of Aboriginal Affairs, threatens to undo this successful delivery of service by imposing a nationwide “formula” that does not take into consideration all the relevant factors of service delivery in this region, says the tribal council.

Among the other NTC services threatened is Ha-Shilth-Sa, a news publication that was established in 1974, along with the website and social media components. These tools keep Nuu-chah-nulth people connected to their communities and families.

There is also the historical records component of the department. Since 1985, the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council has provided audio/visual services for meetings and events throughout the territory. Thousands of hours of taped negotiations in areas like treaty and fisheries have been recorded as a result. As well, general meetings, budget meetings, and directors meetings are held in our archives, as are thousands of hours of recorded cultural events, graduations, princess pageants, and sporting events.

This is a treasure trove of language, song, dance and protocols, and not only Nuu-chah-nulth history, but Canada’s history as well.

The effect of Aboriginal Affairs’ intended funding cuts to tribal councils will be to undermine these supports and others to Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations communities. Alternatives will cost more—much more—and will be borne by First Nations people, not the minister of Aboriginal Affairs, or his advisors, the tribal council contends.

In his Sept. 4 press release, Minister Duncan said “The Government of Canada is taking concrete steps to create the conditions for healthier, more self-sufficient Aboriginal communities.” He said the new formula will ensure funding is focused on “our shared priorities: education, economic development, on-reserve infrastructure, land management and governance programs.”

The Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council is considered a shining example of what can and should be achievable. Canada’s Government threatens NTC’s continued successful service to Nuu-chah-nulth people by resorting to a cookie cutter approach to funding that will harm rather than help in all the areas that Minister Duncan has stated as the goals of the “formula”.

“Massive cutbacks to First Nations organizations are illegal and unconstitutional, and will be met with the full force of political protest,” said Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council President Cliff Atleo.

The Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations are joining with other tribal councils and Aboriginal representative organizations in demanding that John Duncan, minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, cancel these planned cuts immediately.