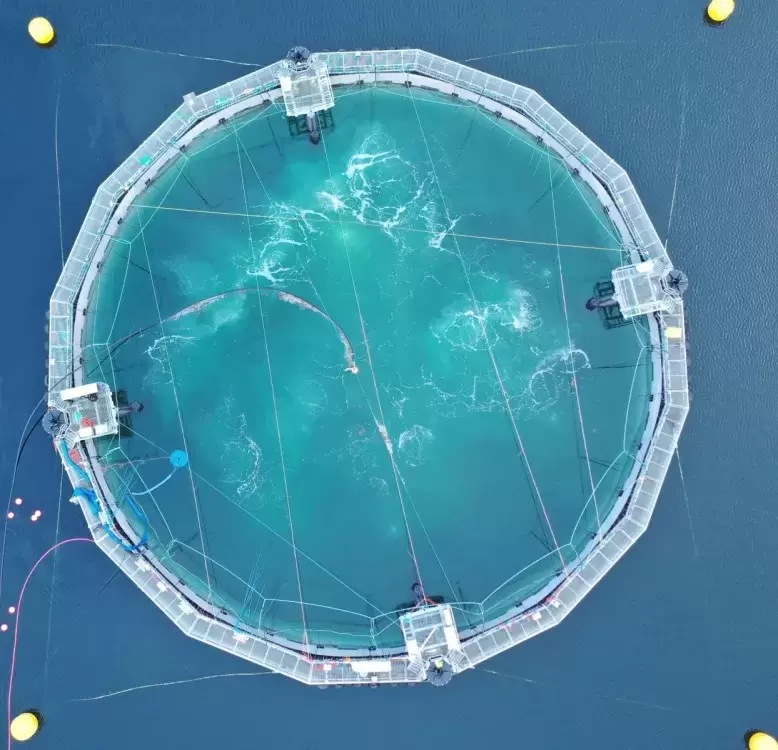

Indigenous and environmental groups are monitoring a containment system trial in Clayoquot Sound designed to eliminate interaction between wild and farmed salmon.

Maaqutussis Hahoulthee Stewardship Society (MHSS) together with Uu-a-thluk, the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council fisheries department, and Tofino-based environmental group Clayoquot Action are watching and analyzing as Cermaq begins testing a semi-closed containment system (SCCS) in Millar Channel.

David Kiemele, Cermaq Canada’s managing director, said the company sees potential in SCCS for several reasons.

“The first is the potential benefits for salmon, as trials in Norway have shown us that the system essentially eliminates the transfer of lice from wild salmon to our farmed populations,” Kiemele said in a news release announcing the trial launch. “We are also excited to see how the farmed populations perform in the system in Canadian waters. In Norway, we have seen our fish grow faster and have better overall performance.”

SCCS is untested in Pacific waters. The experiment, which runs until summer 2022, will analyze performance of Atlantic salmon smolts grown in the system compared to control groups grown in a conventional open-pen system.

Millar Channel lies in traditional Ahousaht territory, and the First Nation supports fish farming through an agreement with Cermaq.

Fish farms in the Hahoulthee of Hawiih operate with consent from Ahousaht hereditary chiefs.

Hereditary Chiefs Economic Development Corporation spokesman John Caton said in July that they were skeptical of the trial while encouraging Cermaq to move to closed containment fish farming by 2025. MHSS hired biologist Danny O’Farrell in September to monitor the trial.

“Work is going on between NTC and Danny in conjunction with but independent of Cermaq,” Caton said. “One of the things they’re doing right now with NTC is called micro-trolling for sea lice. Catching young chinook, one to one and a half years old, catch and release, gathering lice counts, water temperature and water quality data.”

Jared Dick, NTC’s central region biologist, said ongoing Uu-a-thluk sampling of juvenile salmon in Clayoquot Sound, including beach seining of juvenile chum, does not look specifically at the SCCS trial but may give some indication of fish farm impacts in terms of infectious agents (i.e. viruses and bacteria) and sea lice.

Through the spring and summer, NTC counted sea lice on wild juvenile chinook on their out-migration, a co-operative effort with Ahousaht Fisheries and Cedar Coast Field Station, Dick said. They are also working with DFO’s molecular genetics lab at Pacific Biological Station studying gill tissue samples and conducting RNA analyses to determine what may be stressing the fish.

“We counted less than 500 adult chinook in Clayoquot Sound rivers this Fall,” Dick said. “These are extinction levels. What is stressing them?”

Tsimka Martin of Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation was hiking at Cox Bay near Tofino in September when she spotted the SCCS under tow and alerted others of its arrival. Martin is behind the Nuu-chah-nulth Salmon Alliance, which is allied with Clayoquot Action in an effort to have fish farms removed from the sound, a move they feel is vital to save wild salmon stocks.

“We have been monitoring it closely, as closely as we’re able to,” said Clayoquot Action’s Dan Lewis, commenting on the SCCS trial. “It’s just a stalling tactic, a PR statement.”

After receiving word from Martin, Lewis and others visited Millar Channel last month as part of a program they call CSI (Clayoquot Salmon Investigation), observing fish farm activities.

“It seems like a lot of work to go through to partially raise smolts. It’s not a solution to the problem,” Lewis said. Fish feces and viral particles will still leave the system, he said.

“It looks like they’re trying to protect their own fish,” he said.

Feces feed algae blooms, Lewis contends, noting Cermaq experienced an unseasonal bloom last November: “They’re becoming more frequent around the world due to eutrophication, warming water and feeding the algae.”

Brock Thomson, Cermaq’s project director for the trial, said SCCS performs well in Norway but Pacific waters are warmer and more biodiverse.

“We also have different fish welfare concerns, many of which we are hopeful the system will help to mitigate,” Thomson said.

The Canadian trial is adapted to local waters with use of four deep-water intakes roughly 25 metres beneath the ocean surface.

“The hope is that this will potentially eliminate harmful algae and sea lice from entering the system,” Thomson said. “Overall, this technology gives us a greater ability to control water quality within the system.”

An initial control group of 233,000 smolts is being reared in two open-pen nets while 495,000 smolts are in the SCCS. Cermaq plans to transfer fish from the SCCS to the net pen to test performance and effectiveness of the system.

“We are also investigating the feasibility of using this technology as smolt entry sites or nurseries,” Thomson said.

The practice of moving smolts from freshwater to sea pen can be stressful, making them more prone to health risks associated with marine environments.

“By using the SCCS as an entry site, we may be able to reduce stress and minimize exposure for smolts, helping to improve overall fish performance and welfare,” Thomson said.

Clayoquot Action questions why the federal government would subsidize the trial — 15-20 percent of the $5-million cost comes from the Clean Energy Fund — believing public funds should instead support a transition to land-based fish farming and workers along the coast who will be affected.

“This is not for wild salmon,” Lewis said.

“It all circles back to the Cohen commission recommendation No. 3,” that the federal government remove the DFO mandate to promote salmon farming, he added. “We know how DFO handled the (Atlantic) cod and they knew the science then. Their scientists were telling them then and the scientists are telling them now.”

SCCS is designed to eliminate lateral interaction between farmed and wild salmon and thereby reduce the transfer of sea lice between wild and farmed salmon, benefiting both, Cermaq says.

“We will be tracking sea lice numbers on our fish as part of the project and we see this type of technology as potentially being a useful addition to our production approaches in reducing the level of interactions between our salmon and wild salmon,” said Cermaq spokeswoman Amy Jonsson.