News of the remains of 215 undocumented children unearthed at the Kamloops Indian Residential School continues to reverberate through Nuu-chah-nulth communities, prompting the Ditidaht Ha’wiih to venture to another former site to make a statement.

Since the discovery was announced by the Tk’emlúps te SecwépemcKukpi7 First Nations on May 27, many residential school survivors have yearned to uncover evidence of other children who went missing while at the institutions. Now some Nuu-chah-nulth-aht are looking to the ground where the Alberni Indian Residential School stood in various forms from 1893 to 1973, including the hereditary chiefs from the Ditidaht First Nation, who came to the site on Monday, June 7.

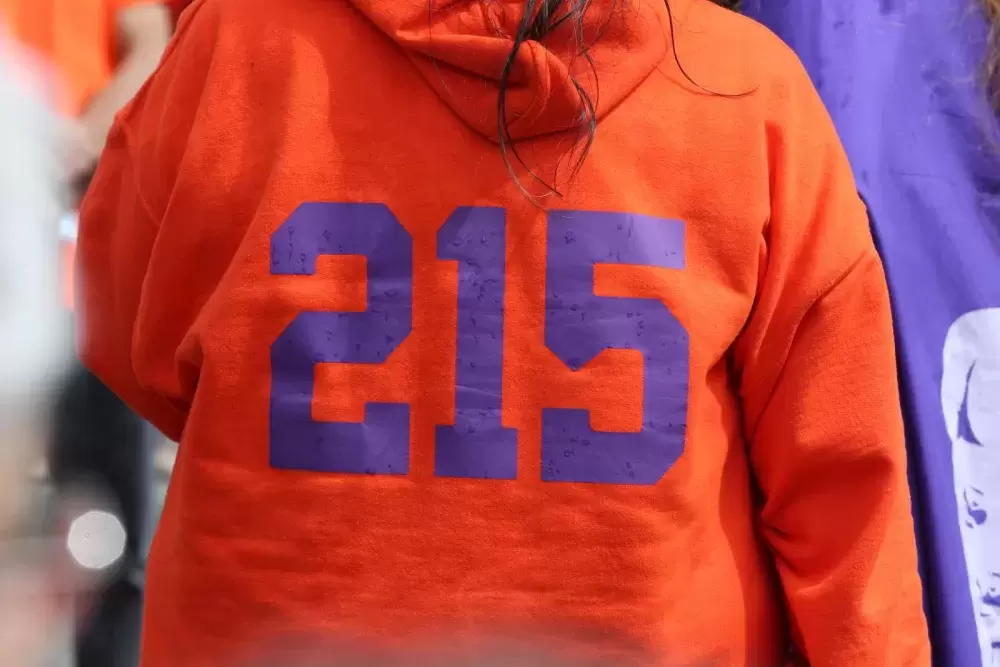

A crowd of several dozen gathered outside of Maht Mahs gymnasium on the rainy afternoon, mostly clad in orange shirts to recognize the First Nations children who attended the assimilationist institutions.

Beginning with comments from Ditidaht member Bookwilla (Charlie) Thompson, he explained that the gathering was intended to honour the 215 undocumented children who were discovered in Kamloops, as well as recognize at least two children with families ties to the First Nation who went missing while attending the Alberni Indian Residential School.

The gathering took place with permission from Tseshaht Ha’wiih, and speaking on their behalf, Robert Watts explained that the children who went missing from the Alberni institution would not be forgotten.

“They want you to know that they’re going to do their hardest to get to the bottom of everything that happened in this building,” said Watts on behalf of the Tseshaht hereditary chiefs.

Ditidaht member Jack Thompson read a statement from the Ditidaht Ha’wiih, as the chiefs stood before the crowd.

“There is no more profound truth than having to come to terms with the death of a child. Equal to the burden, is coming to terms with the deaths of many children. Their stories are our individual stories. Their deaths are our living memories,” he read. “We are children buried in time, we are children living in time, we are children angered in time. We are children and we are survivors of Canada’s Indian residential schools.”

“Let us breathe life into their memory, and let us all breathe life into each other,” continued Jack Thompson. “The story of the Indian in Canada is the story of Canada. Canada’s history is but a single grain of sand on an unending beach within our history, our Nuu-chah-nulth history. Let us unearth this rich history and honour every child in our homes and in our communities. Let us honour all the legacies of hurt and grief and renew our spirits with a promise of hope and prosperity. Let us make every child matter, and let us make every one of us matter.”

Buildings that once housed the residential school are still standing on Tseshaht land, a painful reminder that led the First Nation to formerly request resources to remove these structures so that they can be replaced with a healing centre for survivors. This request was put to the House on Commons on June 1 on Tseshaht’s behalf by Courtenay-Alberni MP Gord Johns.