When reflecting on this past school year, Nancy Logan said COVID-19 gave her students at Haahuupayak Elementary School an added bonus of “survival education.”

Located within the community of Tseshaht First Nation in Port Alberni, many of the school’s students are dealing with intergenerational traumas.

COVID-19 added to those challenges as students worried they’d be putting their grandparents and elders at risk by attending school. Some developed a fear of the outdoors, described Logan.

If students are shut-down and don’t feel safe at school, they’re not able to learn, she added.

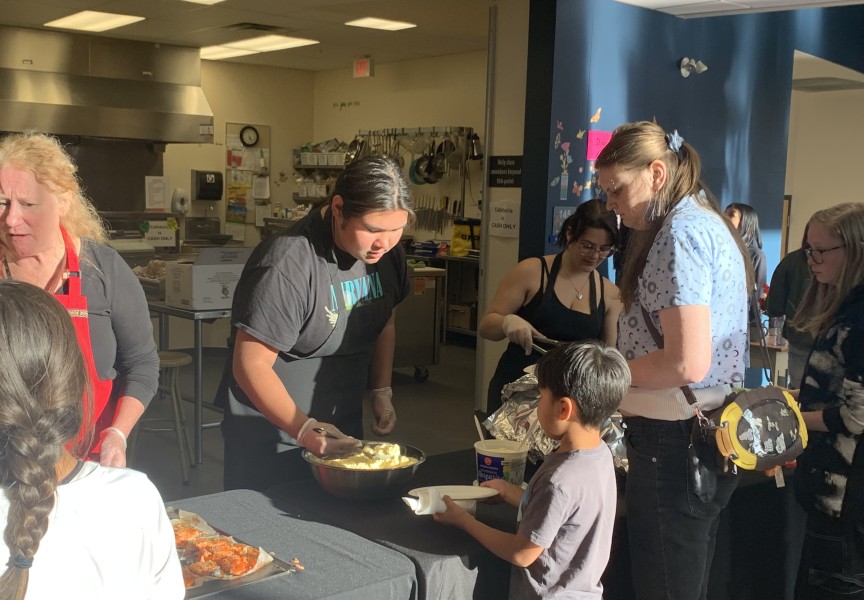

While Haahuupayak has always emphasized project-based learning through things like cooking and woodworking, the pandemic opened the door-way to establish an outdoor learning space, along with a school-wide social emotional program.

“The one part that has been so exciting in this pandemic is the will and the desire to want to do things differently,” said Logan. “It really opened our eyes to that need to move away from textbooks and into the real world.”

For Logan, school should be a place of connection.

“A start to helping [children] ground and deal with their big emotions,” she said.

Helen Lucas teaches the school’s Grade 5/6 class. In her eight years of teaching, she said this year was by far the most challenging.

“In part, because we were all feeling the same,” she said.

As part of her social studies class, students were assigned to identify a community problem and come up with solutions.

COVID-19 was the obvious choice.

After brainstorming, the class concluded that an outdoor learning space would “bring happiness to the whole school” after a dark and disappointing year, explained Lucas.

Not only would it strengthen the students’ connections to their culture and environment, Lucas said it would also provide them with a safe space to alleviate some of their anxieties and sadness.

A recent study, Restoring Our Roots: Land-Based Community by and for Indigenous Youth, was published in the International Journal of Indigenous Health and aimed to demonstrate the many ways learning from the land is beneficial for Aboriginal youngsters.

Targeted assimilation and land theft are central to the historical and ongoing dissociation of Indigenous people from their traditional connection to the land, read the study.

“It is thus paramount that Indigenous youth be given the opportunities to (re)connect with their cultures in safe, accessible spaces [and] places,” the study concluded.

To get the project rolling, Lucas secured a circle of well-being grant and her students followed up by writing “persuasive” letters to Logan asking for additional funding.

With the help of Brenda Sayers, the school’s financial administrator, Logan applied for funding through the First Nations Schools Language and Culture Program, transforming the project into “something bigger than we ever could have dreamed of,” said Lucas.

“This project gave us something to look forward to,” she said. “It’s helped us through a really hard year.”

Describing one of Nuu-chah-nulth’s guiding principles, His-shuk-nish-tsa-walk (everything is one), a classroom doesn’t have the same resonance as does the outdoors, said Lucas.

“To see the trees and use all of our senses to hear, smell, feel and touch the environment while we’re learning just brings everything together,” she said.

Rather than using textbooks to teach about life cycles, teachers will have the ability to bring students into the forest to map out things like what organisms live where, how they are interconnected and what habitat they rely on, explained Logan.

“You see a change in the energy with kids,” she said. “You get them outside and you see them come alive.”

When Kensie Johnson, one of Lucas’ Grade 5 students, thinks about learning outdoors she said she feels “happy.”

“I feel awake,” she said. “I also feel excited to hear all the noises of what’s around us in the world.”

The 10-year-old said she notices a shift in her classmates, too.

“Sometimes they become sillier,” she said. “They also work much faster and calmer.”

The push to incorporate more land-based learning comes from a nationwide quest to “decolonize the education system and honour some of the local knowledge,” said Comeau, vice-principal of the Nootka Sound Outdoor Program.

The outdoor program offers land-based learning to students in the remote communities of Kyuquot and Zeballos.

In Kyuquot, the student population is 100 per cent Indigenous, said Comeau.

Because the community is so isolated, the program usually aims to expose students to new regions through overnight trips to Strathcona Park or Mount Washington. As a result, local areas often get passed up.

COVID-19 became an opportunity to teach children about their local territory.

Activities are planned around the local seasonal calendar, including events like the chum salmon run in September and the herring spawn in March, explained Comeau.

By presenting learning opportunities that are relevant to the student’s lives, Comeau said they are able to tap into their background knowledge which instills them with more confidence in their learning.

“Instead of presenting a foreign topic to [students], it's something they have a family connection to, or a connection to through their culture,” she said. “If you can access that knowledge and present a learning opportunity they can draw from, they don't feel like they're just left high and dry without any of the tools or information to help them in the learning task.”

The Wickaninnish Community School in Tofino was able to continue with some of their regular outdoor programming during COVID-19 because of their geographical location, said principal Drew Ryan.

Working closely with the Rainforest Education Society (RES), the Central Westcoast Forest Society and Tribal Parks, students were able to go on guided forest walks, explore local tide pools, help with revitalization projects and practice their recognition of local plants, explained Ryan.

Whether discussing the shapes of a feather or the patterns on a leaf, Ryan said that more meaningful connections are made through nature that children can apply to their own lives.

“I’ve never met someone who isn’t more regulated and connected when they’re out in nature,” he said. “The learning is more direct, it’s more hands-on, it’s more visceral.”

Around 42 per cent of the school’s population is Indigenous.

With guidance from Gisele Martin of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, along with other local First Nations members, the Rainforest Education Society’s field school program aims to incorporate Nuu-chah-nulth language and history into its teaching practices.

“This is carefully done with permission and communication with First Nations community members, such as Gisele, and through research using Indigenous-led resources,” said Kira de Leeuw, Ucluelet field school coordinator for the Rainforest Education Society.

By bridging the traditional classroom setting with outdoor learning, de Leeuw said it can help develop children’s social emotional awareness.

“A child who may face struggles in that traditional classroom can really blossom into a confident, focused, active participant when learning in the outdoors,” she said.

Leading up to the end of the school year, Lucas’ students at Haahuupayak held a ceremony to bless the school’s new outdoor learning space on June 10.

After a year of feeling disconnected, with students forced to separate from their siblings and cousins, the outdoor classroom was a way of telling them “we’re here and we care about you,” said Lucas.

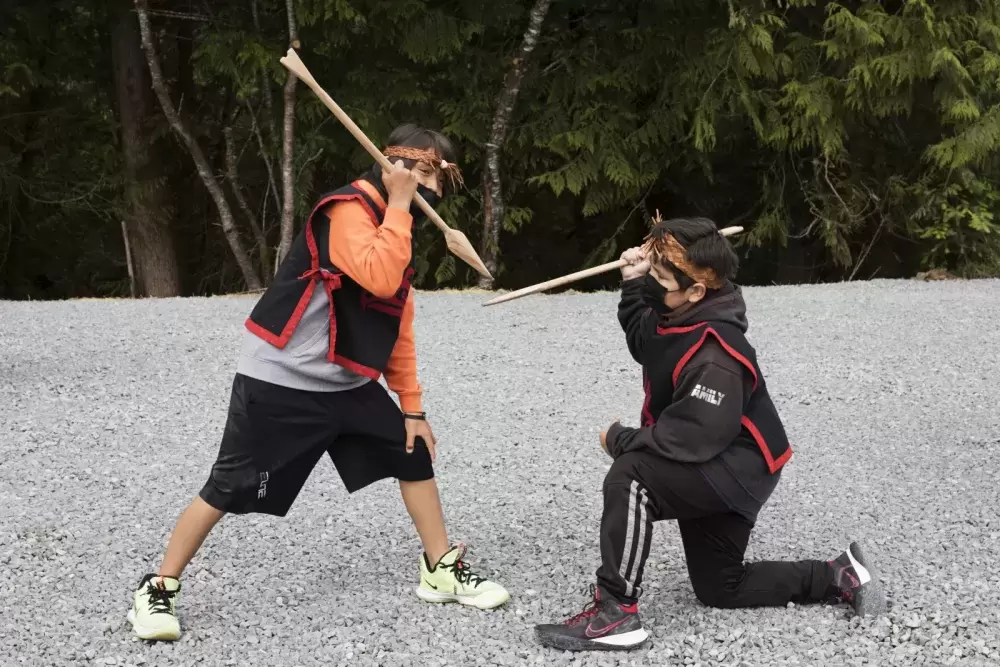

Adorned in regalia, the students chose to dance to a war song and a victory song.

It signified the battle of making it through COVID-19, and coming out on the other end of it with a new outdoor space.

Not only did the project help the students get through the year by realizing their dream, it will help all of future generations that follow, said Trevor Little, the school’s Nuu-chah-nulth studies assistant.

The leadership from the Grade 5/6 class contributes to “the great work of our ancestors,” said Little.

“This place, those children and the fact that they have somewhere safe to go every day – that’s our victory,” he said.