A paper published in April has suggested marine species usually only found on the Pacific coasts are able to survive in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and the recent study has a Vancouver Island connection.

Henry Choong, curator of Invertebrate Zoology at the Royal BC Museum, co-authored the study alongside Linsey Haram of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture in the United States, as well as many others. They say that the results of this study may suggest that coastal species have been able to not only survive, but reproduce on plastic debris that has floated out from the coasts and into deeper sections of the Pacific Ocean.

“Our findings show that coastal species are clearly capable of living, surviving, and reproducing in the open ocean with the aid of plastic pollution, because plastic provides a more permanent, non-biodegradable ‘home’ for them,” says Choong.

The study follows up a previous effort, in which species native to Japan were found on the coasts of Hawaii and North America following the earthquake and tsunamis that rocked the country in 2011.

“[Materials] such as lumber, glass and metal, are made of naturally occurring materials and may not last at sea,” states the study. “However, enduring plastic materials may survive much longer, although degradation rates vary across polymer type, habitat and environmental conditions. Floating plastic materials, such as buoys and floats, built to persist in harsh marine environments, are by nature more durable and buoyant than natural materials, making floating plastics optimal rafts for long-distance and long-term dispersal.”

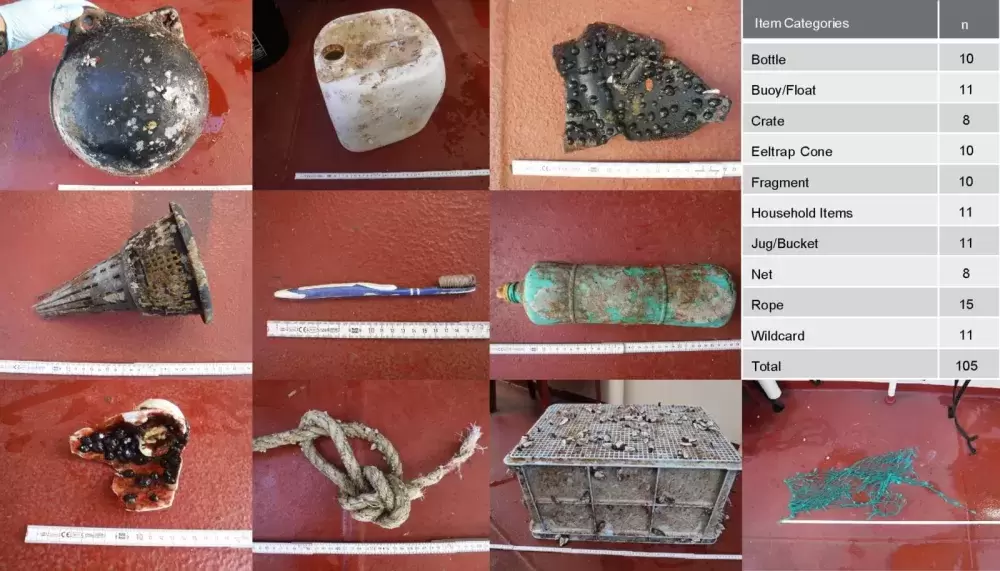

The vast majority of organisms found in the study were invertebrates. These range from crustaceans and sea spiders, to sea sponges, bivalves, sea anemones, and bryozoa, which are more commonly known as moss animals. In fact, the only species found that are not classified as invertebrates would be three distinct types of polychaete worms, also known as bristle worms.

Despite what people may think from the name, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is not actually a massive island created of plastics, as the majority of the debris making it up are microplastics, giving the ocean more of a cloudy look than anything else. A study done in 2018 found that nearly half of the mass was made up of fishing nets in various states of deterioration.

The scientific community was aware of the issue of plastic pollution in the Pacific as far back as the late 1980s, but the extent of the problem was brought to public attention in 1997. That year, a yacht racer named Charles Moore took a route through the patch during a transpacific race, and has been championing the issue of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch ever since. Moore had founded the Algalita research foundation in 1994 with the aim of improving water quality in California, but by 1999 he had transitioned it to focusing solely on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

In an article written February of 2023 for Algalita, Moore compares the level of plastic pollution in the ocean to the Greek myth of Pandora’s box. He believes that, at least in the foreseeable future, cleaning the ocean of the plastics will be near impossible, and that the best option for preserving the ocean is for humanity as a whole to scale back the use of plastics.

“While there may be no hope of cleaning plastic from the environment in the foreseeable future, there is hope that mankind can respect and fear plastic enough to treat it with great care, by designing products and creating take-back infrastructure that makes plastic benign,” writes Moore.

That’s not to say that everyone feels the same way as Moore, however. The aptly named foundation The Ocean Cleanup has made their entire goal to remove as much garbage from both rivers and oceans worldwide, with the main goal being to have removed 90 per cent of all garbage from the oceans by the year 2040.

They too, have an island connection. The Ocean Cleanup’s most recent cleanup system, called System 02 and nicknamed “Jenny,” was first tested in July of 2021, and sailed out to the Garbage Patch from Victoria. On April 4, 2023, System 02’s second iteration made its first extraction, pulling 6,260 kilograms of plastic out of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which also brought them to over 200,000 kilograms removed to date in total. And as recently as May 1, they deployed the third iteration, double the size of the second.

As far as the species now calling the garbage patch home, the experts say more research is necessary to see what the long-term impacts will be. And according to Choong, there are a lot of said experts looking into it.

“This work involves a large group of interdisciplinary scientists and non-profits studying the biology and physics of the eastern North Pacific Subtropical Gyre,” he said.