The team overseeing the rescue of a stranded killer whale is rethinking its strategy, after previous attempts have not managed to move the young orca from a lagoon near Zeballos.

The local Ehattesaht First Nation has named the killer whale kʷiisaḥiʔis (pronounced kwee-sa-hay-is), meaning ‘Brave Little Hunter’. Identified as female, kʷiisaḥiʔis first came to the waters of Little Espinosa Inlet during high tide over three weeks ago with her mother. Locals spotted the adult transient orca stuck on a sandbar early in the morning of March 23, a slaughtered seal in her mouth. They were unable to move the mother from her side, and the adult killer whale died due to drowning later that morning as kʷiisaḥiʔis, who is less than two years old, swam in the nearby shallow water. A necropsy of the mother revealed that she was pregnant and lactating, at least partially feeding the young orca who survived.

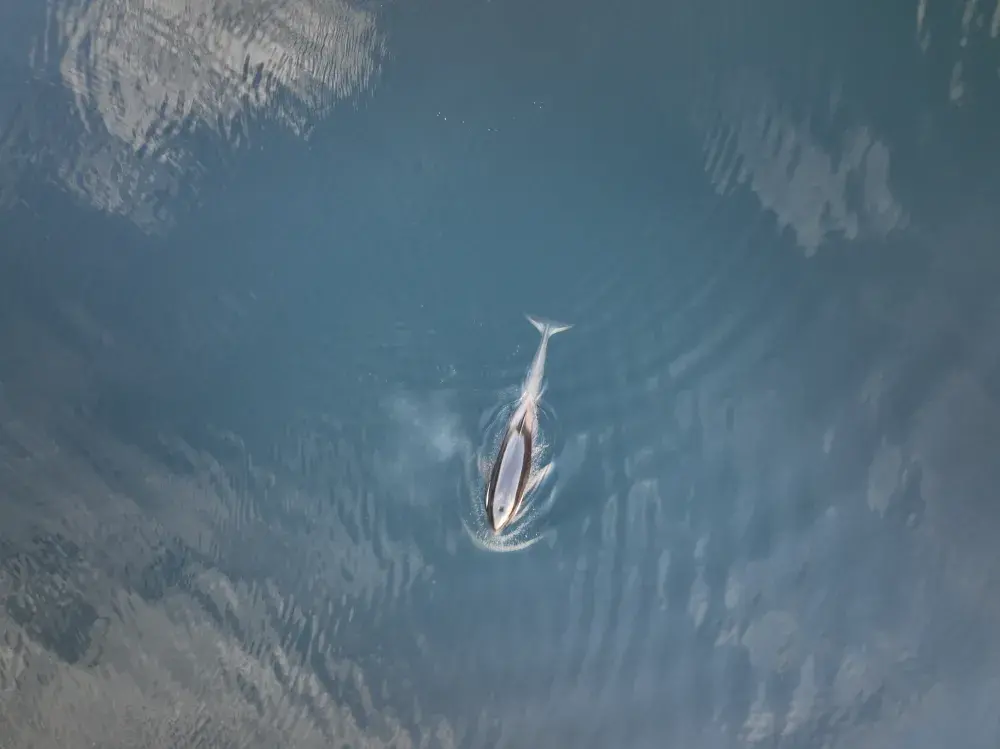

In the weeks that followed kʷiisaḥiʔis has remained active and appears healthy, diving in the lagoon’s waters for six to eight minutes at time. She has been overseen by a growing team of experts and locals, composed of members of the Ehattesaht and neighbouring Nuchatlaht First Nation, as well as personnel from Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Vancouver Aquarium.

She has been seen eating ducks, catching them from below, but it’s unknown what else kʷiisaḥiʔis has subsisted on.

“It’s difficult to tell if she’s eating anything,” said Marty Haulena of the Vancouver Aquarium’s Marine Mammal Rescue Society. “There have been reports of her eating duck, there are seals in the lagoon, which would be her normal food source. There are fish in the lagoon, which wouldn’t be a normal food source but might be an opportunistic food source for her.”

“The immediate need is to get her some nutrition,” he added. “Ideally that’s not in this lagoon.”

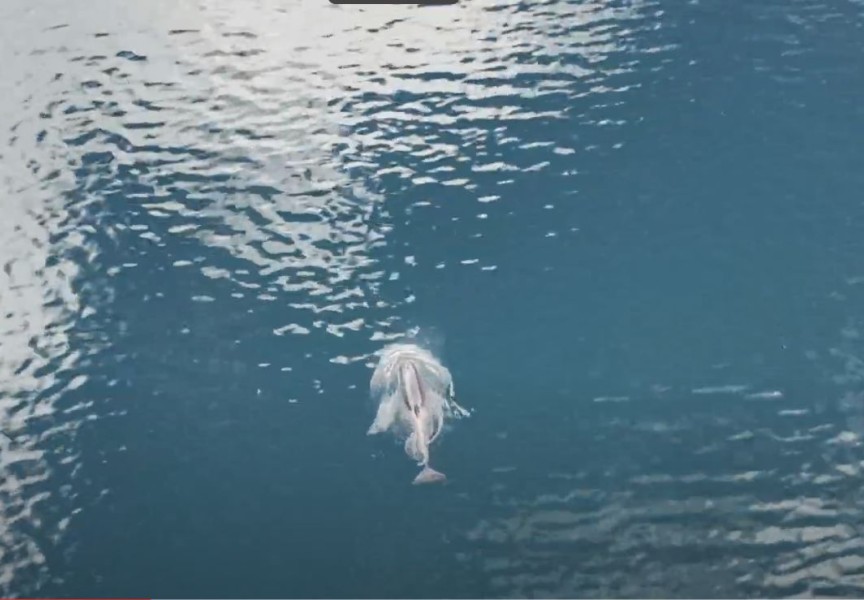

Transient, or Bigg’s killer whales, are more accustomed to the salt waters of the open ocean. The team has observed that the weeks in the lagoon could be having an effect on the young orca’s skin.

“Her skin is starting to turn a little bit white,” said Haulena. “It might have to do with the salinity in that lagoon.”

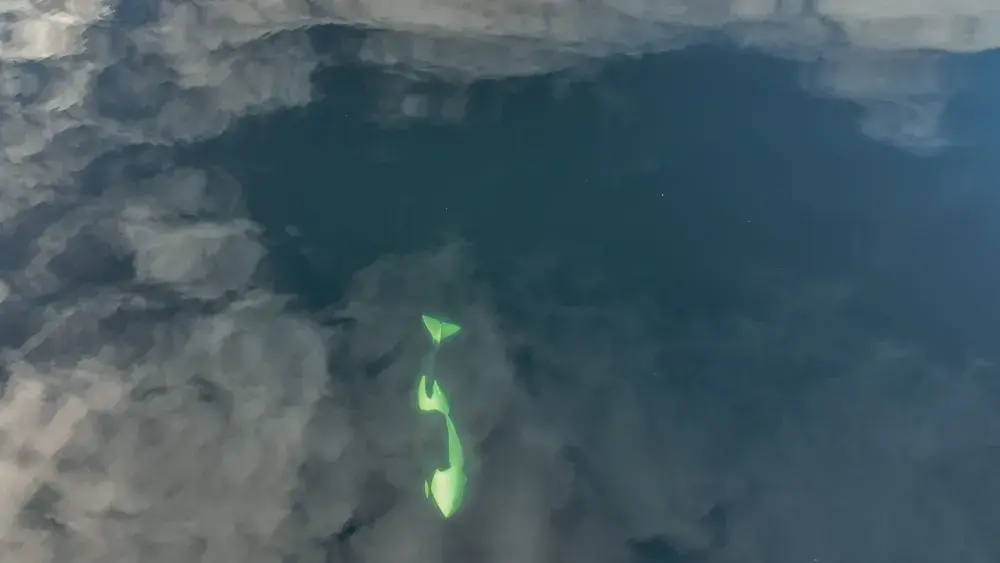

The most recent rescue effort occurred on Friday, April 12, an operation that was the result of several days of coordinated planning. At 6 a.m. a team of 50 assembled at the lagoon, launched half a dozen vessels onto the water to corral the orca into a shallow section that had been carefully mapped. The plan was to get kʷiisaḥiʔis into a sling, lifted by crane onto a truck, then transported over to a barge for the 19-kilometre journey to the open ocean.

But the young whale refused to leave the deeper water where she has spent most of her time, and by 12:45 p.m. the operation was halted.

“It’s very reluctant to leave that area,” said Paul Cottrell, the Pacific Region’s marine mammal coordinator with Fisheries and Oceans Canada. “We fell a little short, but it was quite close. Some of the techniques that we’ve used in the past were less effective.”

The team has so far employed a number of methods to encourage kʷiisaḥiʔis to swim out of the lagoon, including the audio playback of calls from other transient pods spotted in the region and Oikomi pipes suspended from a line of vessels, creating a moving underwater wall of sound. A Hukilau has also been employed, which is an ancient Hawaiian fishing method that entails a row of floats with lines suspended underwater.

“Our little whale may have known our plans too well,” remarked Haulena.

“This is a very smart animal,” observed Cottrell. “With these tried-and-true methods that we’ve used, the animal has figured out them and they’re not effective now.”

The team is now considering an operation in the lagoon’s deeper water, which reaches up to 100 feet down at high tide. This could entail the use of a purse seine, a large net used in the open ocean to catch dense schools of fish like tuna. Like a curtain, a purse seine vertically lowers into the ocean to surround a large group of fish. The bottom of the seine net is then drawn closed, creating an underwater pouch for capture.

“A purse seine is available to us to try to achieve trying to net it - in everything with that, it may take a bigger vessel,” said Ehattesaht Chief Councillor Simon John. “We talked to a friend on that and trying to get his capacity here to work in deeper water if we are going to seine for it.”

Ironically, this fishing method is normally considered a risk to marine mammals, as they get caught in the net with other fish, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries.

“There’s going to be a lot of planning around that to make sure it’s safe for the animal and also all of us that are working in that environment,” said Cottrell.

The end hope is that kʷiisaḥiʔis can eventually join one of the related transient pods that have been sighted off the west coast of Vancouver Island. At the end of March two related pods were sighted in Barkley Sound, and the rescue team hopes that they will pass through Ehattesaht territory, where the young orca could be waiting in a net pen.

“There’s a very high likelihood in a short amount of time there will be some sort of interaction or reunion,” said Cottrell.

Meanwhile, the continued presence of kʷiisaḥiʔis has had a growing impact on the Ehattesaht First Nation, which has its main reserve community of Ehatis just down the road from where the young orca is stranded.

“For as long as we can remember our letterhead has always carried the phrase ‘the council speaks first for the children and secondly for the elders’,” stated an update from Ehattesaht’s elected chief and council. “It is our turn to speak for kʷiisaḥiʔis and to act on her behalf as she is one of our children.”

The First Nation’s chief and council has also noted that the young orca’s unanswered calls have been the hardest part of the past few weeks.

“They are sorrowful and as they go unanswered your heart sinks,” they stated. “The whale experts can tell us only so much but we do know that getting her into the open ocean is the only chance her little voice will be heard.”