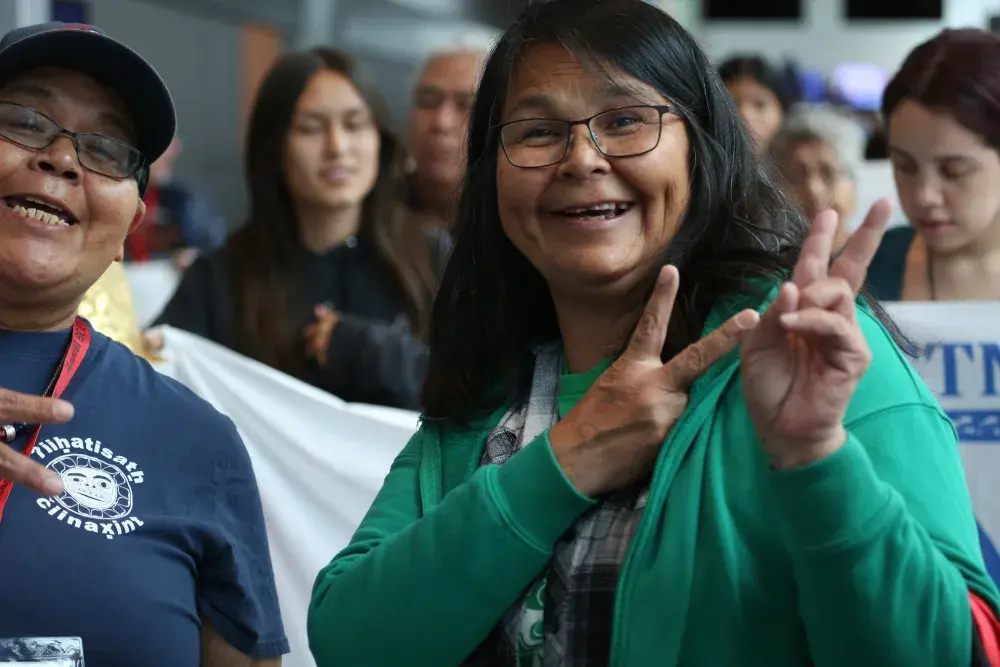

For the 48th time, First Nations elders from across the province have converged in downtown Vancouver for their annual gathering.

This year the B.C. Elders Gathering brought together 1,960 participants -plus their helpers- from over 100 First Nations across British Columbia on Aug. 13 and 14. This is slightly more attendees than last year’s event, which came after a four-year absence due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many travelled for days to reach the venue at the Vancouver Convention Centre, including a group of 18 elders from the Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' First Nations. It took two full days of travel from their home on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island to reach the hectic destination at the Vancouver waterfront.

“Our original hotel got mixed up with the dates, so last minute we had to get hotels for 18 of us,” said Diane Nickerson, manager of Muscim Services for the Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' First Nations. “We’re spread out but we’re close by.”

“It took a whole day,” said Annie John, Ehattesaht’s elders coordinator, who brought their group from the First Nation’s community by Zeballos. “I left 7:30 yesterday morning. I got here at 7 o’clock last night in our hotel.”

Fortunately, the Ehattesaht group made a reservation with BC Ferries. On the day before the gathering the backup of vehicle traffic on the ferries resulted in a two-sailing wait as early as 9:30 a.m. at Nanaimo’s Departure Bay terminal. Some other Nuu-chah-nulth participants had to wait seven hours to get their vehicle on a ferry, and by 3 p.m. there were no more spots for vehicles at Departure Bay for the rest of the day.

“We wouldn’t have been here until today if we didn’t have a reservation,” said John.

Organized by the BC Elders Communication Center Society, for the past few gatherings the event has been held at the Vancouver Convention Centre due to challenges in other locations hosting and catering such a large event. To start the gathering it has become a tradition for the participating nations to pack into the convention centre’s hallway to make a grand entrance into the auditorium.

“When we were outside waiting to march in there was this huge powerful sense of pride,” observed Nickerson. “The build up is so exciting.”

Although the event has been held on the traditional territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) First Nations in recent years, the gathering still assigns a host nation to lead the proceedings. This year the Lil’wat Nation took this role, and proceedings began with addresses from members Frank Wallace and Martina Pierre, who were named king and queen of the BC Elders Gathering. This tradition has been in place since 1982.

Wallace spoke of remembering when he took the job of bringing elders to past gatherings in the mid-1990s.

“The shoe is on the other foot now, somebody had to bring me here,” said Wallace. “It’s been a long time, I never knew I was going to get up to 71 years old.”

“I’m really glad to be here,” he added. “I’m glad to be anywhere.”

On the morning of the first day of the gathering emcee John Henderson of the Wei Wai Kum First Nation referenced difficulties First Nations across B.C. have encountered over the past year, including the loss of resources due to changing climate patterns and the continuing overdoes crisis. These issues brought particularly widespread devastation to British Columbia in 2023; last year more forest burned due to wildfires than any year on record, and with 2,511 fatalities 2023 was the worst so far amid B.C.’s opioid crisis.

“Learn to respect one another, as we have learned from our parents,” reminded Henderson.

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the BC Union of Indian Chiefs hit an emotional moment during his morning address, as he referenced the effects of the ongoing overdose crisis.

“I lost my son five years ago. Carfentanyl,” he said. “But a few days ago on what would have been his birthday we had our first great grandchild…it’s a wonderful, beautiful feeling.”

B.C. Elders Gatherings have become expensive to participate in, as accommodation in Vancouver at the height of the summer tourist season can easily be hundreds of dollars a night for a hotel room. The registration fee for the gathering was $550 per person this year.

“It’s worth it. We did fundraising to help, and the nation sees how important it is to our elders to go,” said Nickerson of the costs. “It would be nice to bring it to the island. Some of our elders are too elderly, the travel is too far.”

“We did some fundraising, but the nation covered most of the cost,” added Carla Short, an elders worker with the Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' First Nations. “It’s something to look forward to.”

“The elders really appreciate getting together with the other elders…being supportive of each other and sharing their experiences and their culture,” said Nickerson. “It’s a real sense of unity when they all march in.”

On the opening day the Lil’wat Nation shared their culture with a series of robust performances. For Frank Wallace, this sort of display of pride is what has carried him through life since he finished at residential school.

“Be part of the community you come from, and be proud of who you are,” he said. “I started to live after I left the residential school and be part of society and be counted.