Albert Lara has always felt some sort of a connection with Indigenous peoples. As a boy he was drawn to totem poles. In his professional life he worked with Aboriginal organizations in California, and while with the California State Retirees he became chair of its Indigenous Peoples Committee.

In his 70s investigations into family lineage brought these associations a step further, leading his research to determine a possible ancestral link with Chief Maquinna of the Mowachaht. By having DNA analyzed through Ancestry.com and matching up archives provided by Santa Clara University, Lara believes he could be a descendent of who he calls “The Lost Children of Chief Maquinna”, two young siblings separated from their tribe in the late 1700s who somehow made their way down the coast to California.

It’s an association that has led Lara and his son Alex to work with the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation, helping to push their aspiration of having the long-removed Whalers Shrine repatriated to Yuquot by the end of this year.

According to Albert’s research, his bloodlines link back to Chief Maquinna (Laqualmiki) Gentiles (1760-1795), and his wife Ysocoto Gentiles (Apenas). Records show the couple had a daughter, Izto-coti-clemot, who had a brother named Yquina.

While they were young, Chief Maquinna sent the two children to live with a neighbouring tribe “as a sign of peace and goodwill”, states Albert’s research. But the children were never returned, and somehow ended up in California.

Church records found by Santa Clara University show that Izto-coti-clemot was baptized by the San Carlos Mission in November 1795, which married her the following spring. She would have been about 22 at the time, and went on to have a son, who carried on the bloodline up to Albert and Alex.

“Of course, you don’t know the level of validity, but there’s connection, there’s maybe some clues,” said Alex of the ancestral investigation. “That led us to go down the rabbit hole further.”

Not quite as much information is available about Yquina, but church records show he also was baptized by the mission and married in 1794 when he was 20, two and a half years before Yquina died.

After discovering this possible connection, Albert and Alex reached out to the Mowachaht/Muchalaht, asking if there was anything they could do for the First Nation. This brought them to meet Margaretta James, president of the Land of Maquinna Cultural Society, who suggested they help with the Whalers Shrine.

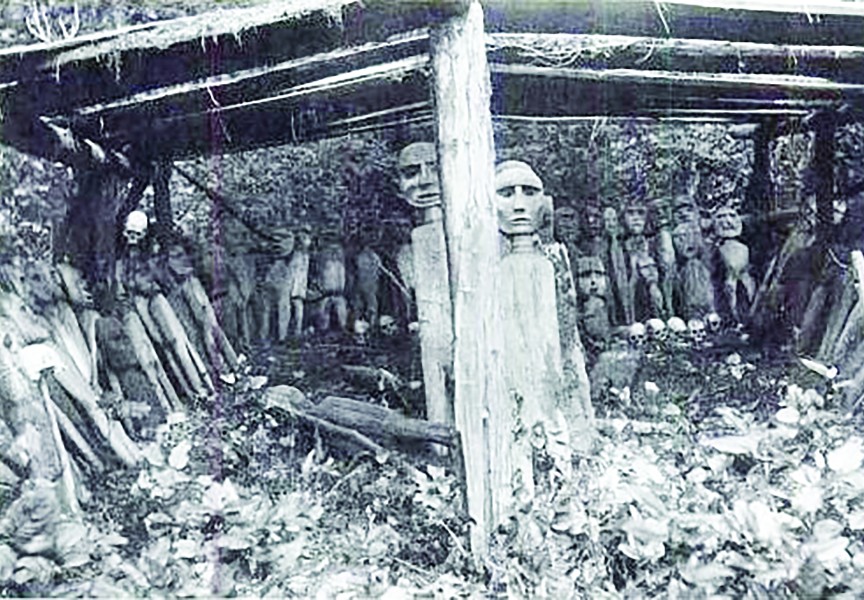

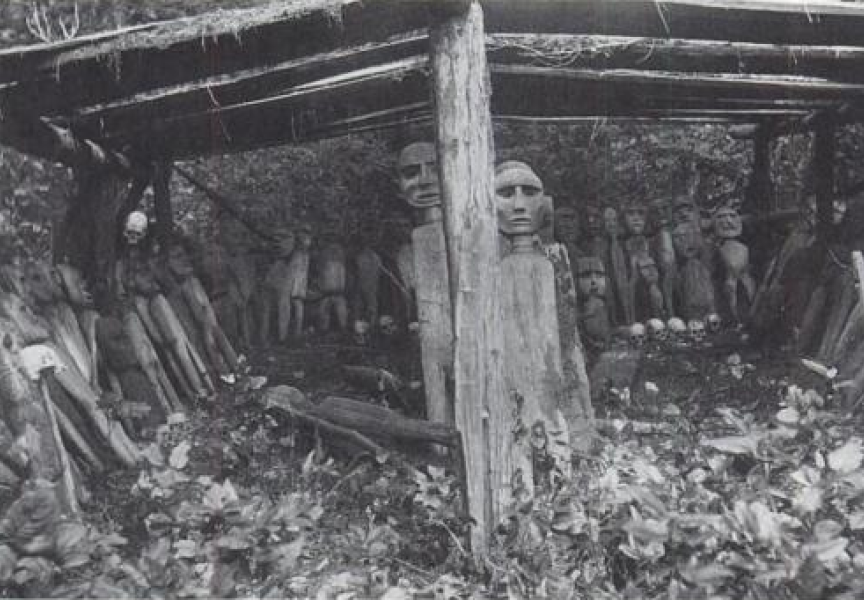

For over a century, the shrine, or Whalers Washing House, has been collecting dust in the storage of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Consisting of 88 carved human figures, four wooden whales and 16 human skulls, at the turn of the century the shrine caught the interest of George Hunt, a Tlingit-English ethnographer, who photographed the mysterious assemblage. This image attracted anthropologist Franz Boas, who asked to buy the shrine on behalf of his employer, the American Museum of Natural History.

The price of $500 was negotiated with two Mowachaht elders, and the shrine was removed from its location at an island on Jewitt Lake - during a time when the tribe had left Yuquot to go on a seal hunt, according to accounts from the time. The disassembled shrine arrived at the New York museum in 1904, where it has remained ever since.

Within the Mowachaht tribe very little was known about the shrine, except amongst the families of whalers who used the site for purification as they prepared for a hunt. The exact location on Jewitt Lake is not commonly known.

“There was almost a secret society,” said Margaretta James of the Mowachaht whalers’ rituals.

Recognized as a National Historic Site of Canada, the Whalers Shrine has been called “the most significant monument associated with Nuu-chah-nulth whaling” in this federal designation. Taken under questionable circumstances that did not appear to involve the permission of the head chief, many within the Mowachaht/Muchalaht believe that the shrine should be returned to its former, secret location.

In the United States the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act actually requires that museums and other federally funded institutions return Indigenous cultural items to their “lineal descendants”. The US Secretary of the Interior can actually penalize museums that fail to comply – but this does not apply to artifacts taken from Canada, something that has held up the repatriation process, said James.

But this is where the Laras’ connections south of the border could help. Alex has a company in Sacramento called Economic Development Solutions, which for several years has worked with Indigenous communities in California on matters like housing, energy and health care. The father and son also have connections with senators in the state.

Alex is pushing for the shrine to be repatriated from the museum as early as October. For the past few months the father and son have joined James and the Mowachaht/Muchalaht Council of Chiefs on a committee formed to bring the shrine back to Yuquot.

“Now, it’s formal, it’s procedural,” said Alex Lara of the repatriation process. “These are the steps. The tribe is going to do everything to get those accomplished with a level of mutual expectation to move forward, get it done.”

On June 24 the Laras visited the New York museum with members from the First Nation to see the shrine components in person. In preparation for its eventual relocation, a prayer and chant were performed.

Albert Lara described the encounter with the shrine as being “very spiritual.”

“It’s something that’s indescribable to say in words,” he said. “To see the view of this world, and then all of a sudden we had this intense awakening. You know it within yourself. You know it within yourself, and each individual has that gift, when there is an awakening substance within yourself.”

“It’s something for the whole world, for every one of us, to learn about - the magic of it and the healing,” added Alex.

“This is a connection that we all have,” said the father. “This is why we are all together here working on getting the Whalers Shrine back, because it is one step for all of us. Either you’re native or you’re not native, there’s still this spirituality of the healing process for all of us. That’s what it represents.”

How exactly the shrine’s components will be transported back to Yuquot is yet to be determined, but the First Nation has decided that, when it eventually comes home, the Whalers Washing House will not be available for public display, said James.