A study conducted in Barkley Sound highlights a resilient sea sponge’s response to its changing environment.

The rare footage was captured by Ocean Networks Canada (ONC) seafloor cameras for more than four years, marking the longest continuous recording of these animals in the wild.

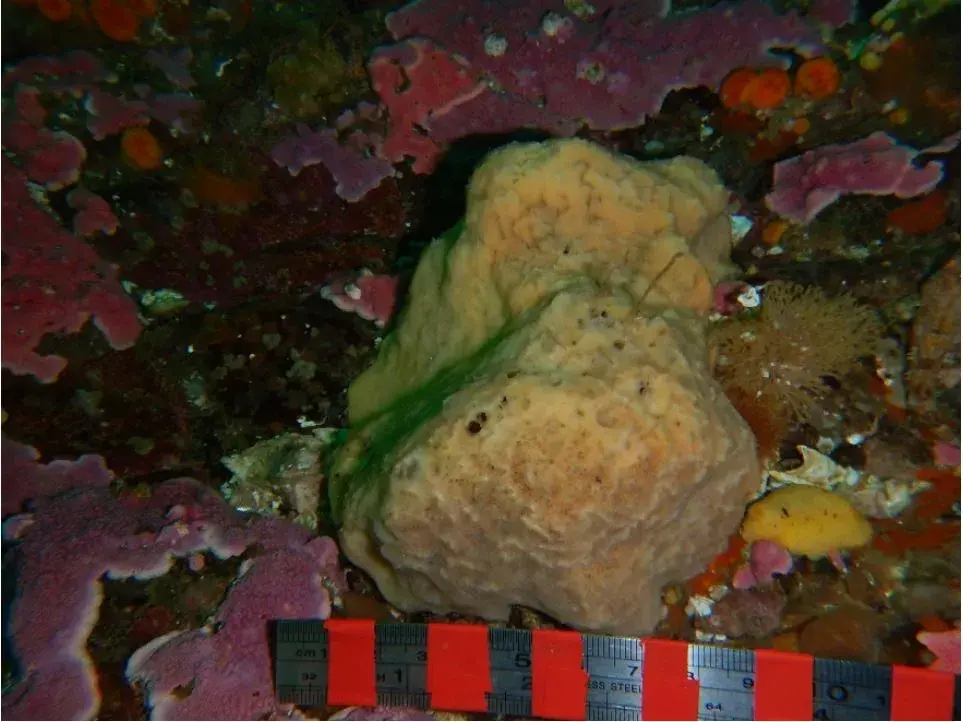

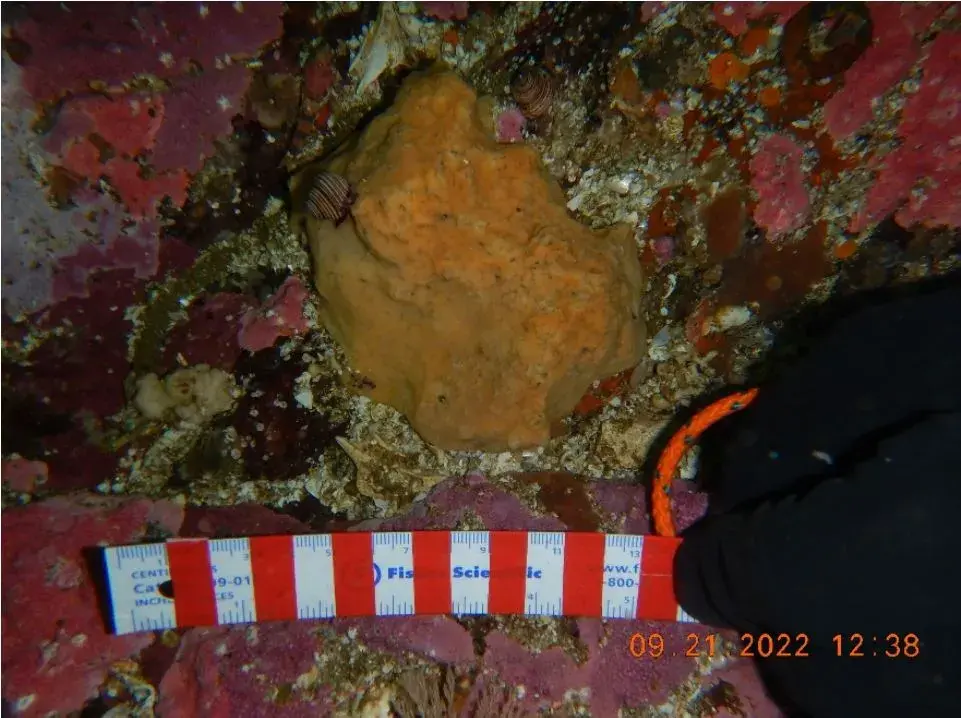

The baseball-sized sponge, nicknamed Belinda by the researchers, was recorded by an eight-camera array and scientific instruments deployed at Folger Pinnacle, a site within ONC’s NEPTUNE (North-East Pacific Time-series Undersea Networked Experiments) subsea observatory off the British Columbia coast.

“To understand sponge behaviour it’s important to understand other animal behaviour. It helps me know how similar they are and how different they are,” said Sally Leys, principal investigator of the project and a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta.

Researchers at the University of Alberta, University of Victoria (UVic), and ONC observed Belinda’s daily, yearly, and seasonal changes in size, shape and colour.

The cameras were rolling for the sponge’s sometimes daily “sneeze-like” contractions as it shrank prior to the winter hibernation, as well as during the marine heatwave (aka the Blob) in the Pacific Ocean off North America between 2013 to 2016.

Leys said a main take-away from the research project was how active sponges actually are.

“Sponges are really active, with no muscle or nerve, and I know a lot of the sponge biologists have gone, ‘Wow, I didn’t even know that’,” Leys said. “In the winter the sponge is very quiet. They basically stop filtering, stop being active and wait out the winter season of storms and low food because there’s not much food when there’s no sunlight. This kind of an animal has annual cycles that are really effected by global cycles.”

Leys said sea sponges can range in size. Some are large enough for divers to actually fit inside them and some are small enough for hermit crabs to live in. Sea sponges can have life spans of a minimum 12- 15 years but some have been recorded as old as 400.

“There’s nothing that should really stop them if they’re in good food conditions and a lot of flow,” Leys said.

Leys added that most sea sponges are protected from warmer ocean waters on the coast of Vancouver Island and continue to thrive deeper down.

“We’re fortunate in the North Pacific that the animals in deeper water are still sort of protected from [warming ocean waters] because the surface warm water doesn’t usually reach down as far,” Leys said. “In the inter-tidal areas, in shallow areas, the water can get very warm and the sponges will just die.”

The purpose of a sea sponge is to filter out tiny particles, mostly bacteria, from the ocean water, digest that and poop it out onto the ocean floor for other sea animals to eat.

“They filter the water so they obviously take a lot out, but they provide food in a format to other animals, so other animals can eat the bigger poop waste,” Leys said. “The sponges are eaten by sea stars and sea slugs.”

According to a news release from ONC, long-term monitoring of sedentary animals like sponges is rare and the study provides insight into the impact of environmental conditions such as water quality and temperature, both of which are affected by climate, according to the research team.

“Sponges provide a vital service for marine ecosystems by filtering the water and recycling nutrients – yet this is the first-ever long-term monitoring dataset,” said Dominica Harrison, lead author of the publication and a UVic graduate student in the release. “Our study reveals how responsive and dynamic sponges are in their natural habitats but beyond that, these data are helping us explore how environmental changes tied to climate change might impact the vital ecosystem functions that sponges provide.”

Although the camera array was removed in 2015 with the conclusion of the project, divers have confirmed as recently as late 2024 that Belinda remains at Folger Pinnacle.

Ongoing monitoring could reveal more about how sea sponges like Belinda respond to changing ocean conditions.

“Eyes in the water tell you a lot. Long-term monitoring is essential to document both the warming changes and how they affect the seafloor, but also, how animals are resilient to change and may come back if they can adjust,” said Leys.