Recent data on Pacific herring presents encouraging indications of a rebound, but there’s currently too many marine mammals eating the small fish for the species to return to what was seen decades ago, according to a study presented to Nuu-chah-nulth leaders.

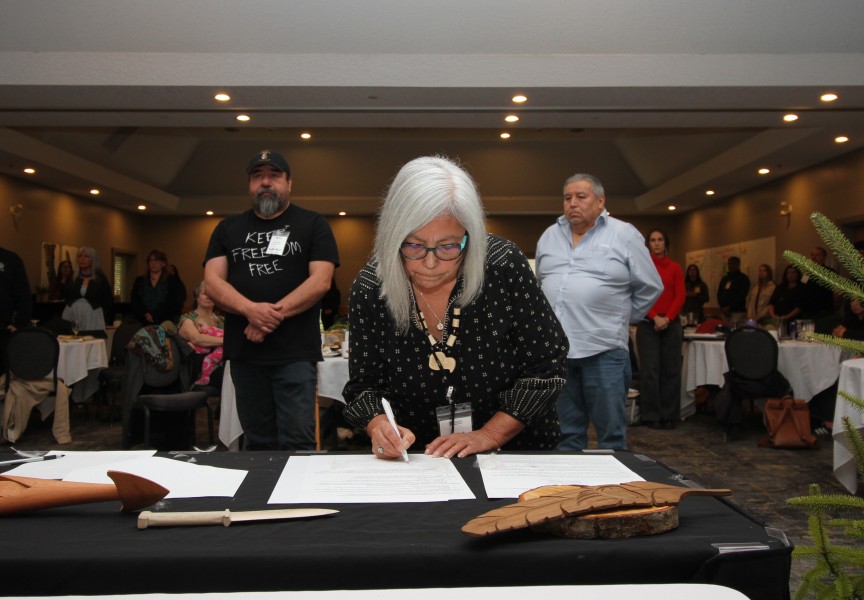

Jim Lane, Uu-a-thluk’s acting program manager, gave a presentation on the four-year herring predation project to the Nuu-chah-nulth Council of Ha’wiih Forum on Fisheries in February. Funded by the B.C. Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund, the study was jointly conducted by Landmark Fisheries Research, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s Ua-a-thluk department.

Data shows a dramatic increase in the populations of steller sea lions and harbour seals on the B.C. coast since hunting the animals was banned in the late 1960s. Sea lions on the west coast of Vancouver Island dropped to less than 2,500 in the mid 1960s, but their population has steadily grown to over 10,000. British Columbia’s harbour seals also declined to approximately 5,000 in the late ‘60s, but after the hunting ban numbers surged to over 10,000 by the ‘90s, a level that has remained stable since.

“Those populations have increased almost exponentially,” said Lane of the pinnipeds.

Pacific hake also prey upon herring, but the population of this fish has fluctuated in the region since 1970.

“When water temperatures are cool, there’s less hake that migrate in,” explained Lane. “When water temperatures are warmer, we get a lot more hake migrating into the west coast of Vancouver Island. When it’s really warm they go all the way to Haida Gwaii.”

Meanwhile, the number of humpback whales off the B.C. coast has risen sharply since the 1990s, growing from approximately 2,000 to 5,000 over the last three decades. An estimated 13 per cent of this population is feeding off the west coast of Vancouver Island, where humpbacks comprise 70 per cent of herring predation, according to the study.

“Humpbacks are so large, their consumption of herring proportional to those other predators – even hake – outweighs them in their impacts,” said Lane.

The Biologist also noted that there are far fewer older herring in Nuu-chah-nulth territory than 40 or 50 years ago.

“That might be to do with preferential animals such as humpback whales and others eating the older herring as opposed to the younger herring,” he said.

Calculations into herring biomass show the species peaking in 1975 at over 200,000 tonnes off the west coast of Vancouver Island – a number that declined to under 50,000 in the mid 2000s. In recent years the biomass had increased, growing from under 15,000 tonnes in 2015 to 65,500 last year in the region.

But so has the amount of herring getting eaten by humpback whales and other predators, and this is why Lane doesn’t expect that the species will return to the volume that fed coastal fisheries in the 1970s.

“There’s just too much mortality from predation that didn’t exist back then,” he said. “Predator consumption is approaching total biomass that’s being produced. There’s a lot of herring being reproduced - so the recruitment is really good- but they’re getting eaten at a fairly high rate. That really affects rebuilding and what you can expect from rebuilding.”

Harvest quota increases in 2025

This spring herring fisheries across the West Coast are wrapping up, after enjoying a season with an increased catch quota and new harvest opportunities. In recent years the Strait of Georgia has been the only region to consistently host a commercial seine and gillnet herring fishery, where the catch quota increased from 10 per cent of the species’ estimated biomass last year to 14 per cent in 2025. This fishery was open March 5 -14, with a maximum harvest of 11,600 tonnes.

With the intent of catching female herring while they are full of eggs, smaller commercial seine and gillnet fisheries also took place off the central B.C. coast and near Prince Rupert, with respective harvest rates of 4.7 and five per cent.

Some groups see the commercial herring fishery as an unsustainable activity that threatens the species’ ability to rebuild, including WSÁNEĆ hereditary chiefs, who in November demanded an immediate moratorium on the catch due to the fragility of stocks.

In an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa, Fisheries and Oceans Canada contends that this year’s harvest numbers follow “precautionary approaches that support the long-term conservation of stocks” that are based on “peer-reviewed science advice”.

Herring are considered a keystone species for the B.C. coast, making up a significant portion of the diet of salmon that many First Nations consider foundational to their ancestral culture and health. For two decades Nuu-chah-nulth have opposed a commercial herring fishery on the west coast of Vancouver Island, but this year a commercial spawn-on-kelp harvest took place. DFO expected that the commercial harvest of herring roe (eggs) on kelp would remove just 1.3 per cent of the region’s biomass, an activity that occurred with the approval of the Nuu-chah-nulth fisheries forum.

“Recent research indicates 78 per cent of the herring used in a closed [spawn-on-kelp] operation survive, compared to 0 per cent in seine and gillnet fisheries,” wrote Wickaninnish, Cliff Atleo, chair of the Council of Ha’wiih, in a letter to DFO in November.

Even still, not enough herring have returned to Barkley Sound for Tseshaht members to enjoy siiḥmuu, herring eggs that collect on branches, in their home territory. Since 2004 the First Nation has spent $20,000-50,000 annually to purchase herring eggs from Bella Bella, said Tseshaht member Les Sam during the February fisheries meeting. He recalls when Tseshaht members once waited in the Broken Group Islands for signs of the spawn, notifying boats in Port Alberni when it came time to collect.

“As a young man, young kid, the herring spawn was almost like Christmas for us,” said Sam. “Everybody worked together to drop trees for other families for the harvest. We didn’t leave anybody out.”

Sam recalls when his pickup truck was filled with siiḥmuu to be brought back to the main Tseshaht reserve next to Port Alberni.

“My late dad Chuck Sam, he said, ‘You put a tarp out in the front yard, and you empty that truck out onto that tarp, and you phone all the people of Tseshaht to help themselves’,” said Sam.

Most of the herring catch goes to Japan, where markets are hungry for the females loaded with eggs. Sam reflects on overharvesting in the 1970s that led to the species’ decline.

“It was like a gold rush and they overharvested it. Warnings were sent out,” he said. “In our territory there’s no longer a feasible spawn there to bring home to the people. It’s been gone since 1983. It left us to be beggars for that resource.”