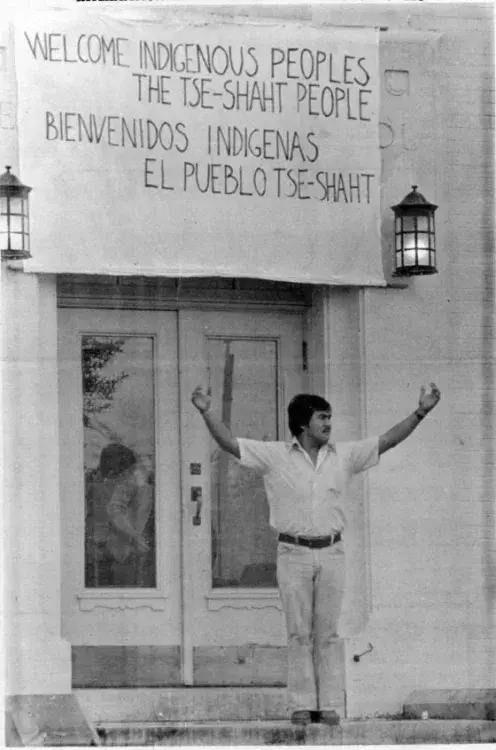

It’s been just over fifty years since the 1975 International Conference of Indigenous Peoples was held on Tseshaht territory – a gathering for international Aboriginal solidarity that took place in the former Alberni Indian Residential School.

Indigenous representatives from 19 countries attended the inaugural conference, which made up about 260 participants and 135 observers.

George Manuel, who at the time was the chief of the National Indian Brotherhood (now the Assembly of First Nations) approached Tseshaht leader George Watts to host the conference in Port Alberni from Oct. 27 – 31, 1975.

The conference was organized to bring together Indigenous peoples from across the world to discuss shared struggles of colonization and discrimination. The gathering also aimed to establish a global organization that would advocate for their self-determination, land rights and cultural integrity, particularly at the United Nations (UN).

The World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP) was formed following the conference. This was the first global Indigenous organization to present a unified voice for Indigenous peoples at the UN and other international forums. The WCIP was granted Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) status by the UN Economic and Social Council, allowing Indigenous representatives to participate and lobby at the UN.

Prior to the 1975 conference, Nuu-chah-nulth members were passionate about making changes towards self-governance, similar to many other Indigenous peoples around the world.

“We needed to change things within, in terms of people exploiting resources and using or disregarding our rights in order to access those resources,” said Richard Watts from the Tseshaht First Nation in a documentary about the 1975 conference. “It impacted us as First Nations and our rights were ignored, our livelihood, hunting or trapping were affected by those decisions.”

Watts said during the conference, the more the attendees talked amongst themselves, the more they realized they were all suffering from the same oppression.

“Whether it be the Sami people (Norway) or the North American First Nations people, it was always the same; that people wanted to access the resources to stimulate their economies and they all saw us as being in the way,” Watts said in the video. “I remember people from South America who were afraid for their lives because they were afraid they would go home and be assassinated simply because they spoke up and talked about what was going on.”

Shared struggles became obvious to the large group of attendees and the idea of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples was born.

The topics discussed and adopted at the conference, including the right to self-determination and the protection of traditional lands, laid the groundwork for future human rights efforts, most notably the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which was adopted more than three decades later.

Bringing together hundreds of delegates was no easy task, but one organizer said it was a team effort. Dennis Durocher played an integral part in setting up the accommodations for the large group.

“I was asked by George Watts at the time to help get the facility ready…it was the old (Alberni Indian) residential school that had been closed down for a couple years already,” Durocher said. “We had a big job trying to get the building ready.”

Durocher said some delegates slept in the old dorm rooms that had been previously used by students of the residential school. Durocher was also a part of a team who helped organize all the meals, security, transportation and evening activities. Durocher and his wife, Sara, were a big help with offering translation services as they both speak Spanish.

Being so involved in the organizing, Durocher was able to attend much of the conference.

“This was the inaugural conference of the World Council of Indigenous People where they accepted and agreed upon a charter and they agreed that they would carry on,” Durocher said. “A part of that agenda was to achieve some sort of UN recognition for the legitimacy of this organization to represent Indigenous claims for justice at the United Nations and for reconciliation. They did achieve that.”

Many strong and long-lasting relationships were built at the conference among the delegates, especially between some Nuu-chah-Nulth members and Indigenous peoples in Bolivia. The strong bond amongst the groups helped the Bolivian’s in their fight against colonialism and military dictatorship, contributing to a radical shift in politics for the South American country.

Before dissolving in 1996, the WCIP was devoted to developing unity among Indigenous peoples around the world, strengthening their organizations and fighting against racism and injustice. The WCIP represented more than 60 million Indigenous people worldwide.