An Atlantic salmon was caught in the Atleo River by an Ahousaht fisherman east of Flores Island this week, following dozens of reports of other recent catches of the species at various locations around Vancouver Island. Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Atlantic Salmon Watch program confirmed just three cases of Atlantic salmon that were caught off B.C.’s coast from 2011-17. But since a fish farm in Washington State collapsed on Aug. 21, releasing over 150,000 Atlantic salmon into the Pacific, numerous catches of the species have been reported, stretching as far north as Campbell River.

The incident from the Cook Aquaculture facility has reignited debate over farming fish in the Pacific Ocean. Days after the net pen collapse in Washington State, a small group led by Ernest Alexandra Alfred, Hereditary Chief of the Namgis First Nation, occupied the Marine Harvest Salmon farm by Swanson Island, 17 kilometres east of Alert Bay.

“The sheer amount of disease and wild herring in the pens is out of control!” said Alfred in a press release, stressing that the group will remain at the facility until the B.C. government cancels Marine Harvest’s licence. “We have no food fish again this year, our wild salmon runs are collapsing and the salmon farming industry is a herring fishery that no one knew about!”

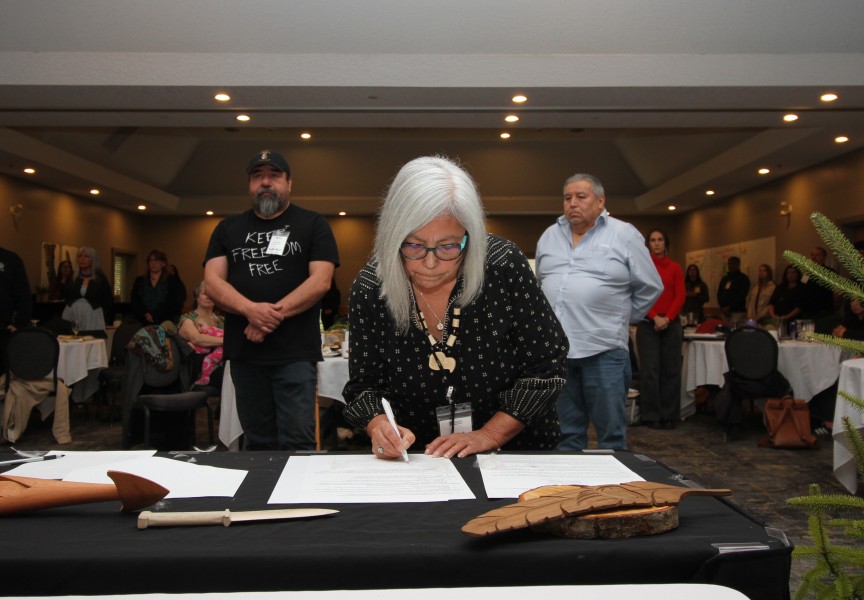

Days after the Namgis occupation members of the Musgamagw Dzawada’enuxw boarded the Wicklow Point Salmon Farm 50 kilometres east of Port Hardy in protest. Then on Aug. 31 the B.C. Assembly of First Nations, the First Nations Summit and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs released a joint statement opposing fish farms in the Pacific.

“B.C. must begin its transition from dangerously reckless open net-pen fish farms to the safety of land-based closed containment aquaculture,” read the statement.

On the other side of Vancouver Island, fish farms continue to operate in Nuu-chah-nulth waters under agreements aquaculture companies have made with First Nations. In Tla-o-qui-aht territory Creative Salmon simultaneously operates four fish farms, employing 55 people year-round to oversee the production of chinook salmon for markets in the United States, Canada and Japan. After decades on Vancouver Island’s west coast, Creative Salmon finalised an agreement with the Tla-o-qui-aht in 2014 that prohibits underwater nighttime lighting and antifouling agents in the nets, with a fish density limit of one per cent of the total space in the pens.

Elsewhere in Clayoquot Sound, Cermaq employs 250 people at its aquaculture facilities. Through an agreement the company has with Ahousaht, over 30 per cent of this workforce is First Nations, making Cermaq a valuable employer for the coastal community. Cermaq also offers training, educational programs, salmon enhancement funding and business opportunities to the First Nation, said Laurie Jenson, the company’s communications and corporate sustainability director.

“The employment goal is to have 50 per cent employment from the Ahousaht community for the West Coast operations,” she said. “We are not there yet, but it continues to be a goal.”

Like other West Coast aquaculture operations, Cermaq raises its salmon in land-based freshwater facilities for the first year of the life of a fish. Then the salmon are moved to net pens in the salt water of the Pacific, where they grow for another 18 months. Three per cent of the farm pen area contains fish, noted Jenson.

“Farming them in ocean pens in low densities is the best way to keep them healthy and grow them into the best quality food,” she said.

Jenson added that maturing the fish in land-based facilities is currently not feasible due to the space, electricity and infrastructure that would be required.

“To grow the equivalent market-size fish on land will take large tracts of clear-cut land with a big power source,” she said. “That land would thus be closer to markets, so we would also lose the jobs and economic opportunities that ocean-based farming gives local communities.”

As Atlantic salmon are not native to Pacific waters, criticism of farming the species on the West Coast continues. In a statement on Sept. 1 the Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde stressed his support for Indigenous communities who oppose aquaculture in their territories.

“I stand with First Nations in B.C. in their long struggle with federal and provincial government to fully recognise and address the threat of salmon fish farms to wild salmon,” he said. “First Nations have long identified the threat of the fish farm industry to wild salmon that have sustained our peoples for generations.”

According to Atlantic Salmon Watch, the farmed fish have not shown a threat to their wild Pacific counterparts.

“If this non-native species became established in local waters, we would see them in their multiple life stages, particularly juveniles in our coastal streams,” stated the program’s website.

The DFO has shown no evidence of Atlantic salmon colonising in B.C. over the last 20 years, according to the B.C. Salmon Farmers Association. This organization advocates for producers in the B.C. industry, which generated over half of Canada’s $907 million in farmed salmon sales in 2015.

“Atlantic salmon take well to the farming environment,” said the association in an email to the Ha-shilth-sa. “Through years of animal husbandry practices and advancements in vaccines, populations are able to be kept very healthy and have a high rate of survival from egg to plate.”

“Escapes from B.C. salmon farms are rare, and escaped fish pose little risk to Pacific salmon because they cannot interbreed and cannot compete with the Pacific wild salmon when it comes to breeding,” added Jenson of Cermaq. “Our Atlantic salmon have been deliberately bred and raised as domesticated animals, similar to other domesticated farm animals.”

The Union of BC Indian Chiefs states that aquaculture sites are focal points for hazardous levels of parasitic sea lice as a well as viruses and other diseases that afflict farmed fish, but the B.C. Salmon Farmers Association contends that salmon in net pens are healthy.

“Farm-raised salmon are vaccinated against the vast majority of pathogens endemic to the North Pacific,” said the association. “This results in a very high degree of health of the population with over 90 per cent surviving through to harvest – compared with less than two per cent of salmon in the wild that survive from birth to return to spawn.”

Since the 1970s the domestication of fish in B.C. waters has grown to nearly $500 million in sales, driven by $65 million in salaries and wages earned by those working in the aquaculture industry. Seventy per cent of B.C.’s farm-raised salmon are exported, and despite calls to remove net pens from the Pacific, the province’s economic reliance on the practice makes such a change to the industry unlikely in the near future.

But as reports of Atlantic salmon continue to come in from fishers, federal authorities plan to monitor the extent to which the Cook Aquaculture escape could affect coastal water by monitoring B.C. streams this fall. Fisheries and Oceans Canada advises anyone who catches an Atlantic salmon to keep the fish and report it to 1-800-811-6010.