Early in the morning of Friday, Jan. 3, a heavy rain alert was issued for the west coast of Vancouver Island. The battering that followed would keep smaller boats docked on Ahousaht’s shore, leaving travellers to the Flores Island community to rely on larger vessels capable of cutting through the deep waves.

“Southeast winds will increase throughout the morning and eventually peak at 80 kilometres an hour for exposed sections,” cautioned a message from Environment Canada. “High winds may toss loose objects or cause tree branches to break.”

Within Ahousaht’s T-Bird Hall half a dozen people sweat over duck, venison, halibut, clams and salmon that cover metal counters in the community building’s kitchen – the harvest from the First Nation’s surrounding territory. Outside the kitchen rows of tables span the room, a few men sit awaiting the crowd that will soon gather. The building intermittently falls into darkness as the power cuts out, leaving the kitchen crew with a lone work light hanging from the door. Some chuckle at the familiar trait of life in the remote community.

By nightfall the T-Bird Hall was packed with hundreds – a significant proportion of Ahousaht’s on-reserve population of about 1,000. The events that would follow over the weekend were held in honour of three late members of the Keitlah family, including one who “lived a full circle of life,” according to his sister, and two others whose time on this earth were cut short by tragedy.

The dinner was held in honour of Nelson Keitlah, an Ahousaht leader who died in 2016. As a young man in the 1950s Keitlah was selected by his nation’s Hawiih to be the first chief councillor. He was among the group of men who organized 14 Nuu-chah-nulth nations into the West Coast Allied Tribes in 1958, a collective that later incorporated into the West Coast District Society of Indian Chiefs in 1973, and is now the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council.

Keitlah lived to be 82, an expansive life that brought no need for a memorial potlatch, said his sister, Betty.

“My brother told me, he said in Indian, ‘Don’t have a party for me, because I’ve lived a full life’,” she recalled. “In our teachings if it’s an elder there’s no potlatch because they had a certain circle of life.”

Besides his political leadership, Keitlah was a cultural repository of Ahousaht traditions. He was among the declining number of the First Nation’s members able to speak his ancestral tongue fluently.

“He knew hard words. We would very seldom use the words nowadays,” said Betty. “Nelson would know right away. I’ve got them written down, some of the words that we hardly use.”

Keitlah was also a composer of traditional songs, some of which have not been heard for several years. On Jan. 4 some of those songs were brought out and performed during a memorial event for two other members of the family: Levi Keitlah, who drowned Jan. 4, 2014 in Clayoquot Sound at the age of 32, and Nadine Marshall, whose body was found behind a dumpster in Victoria’s Esquimalt area on Aug. 3, 2012.

“It was very questionable about how she died,” said Betty of Nadine Marshall, who was Nelson Keitlah’s daughter. “My brother, he kept wondering and the cops were very uncertain about her death.”

“They died very sudden in an accidental way,” she added. “Levi, he drowned. He used to work in a fish plant here.”

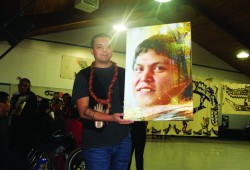

The memorial event that ensued followed strict protocol, including a request that no photographs were taken during a “drying of the tears” song that began proceedings. This piece was composed by Nelson Keitlah, and banners kept by the family for years were unveiled to hang behind the dancers.

“In our culture, us west coast people, we put the song and dance away for a while when they pass on. Even the names, nobody uses them,” explained Betty. “If a person is named Nelson he’s got to put it away for a couple of years at the earliest.”

Although many of those who travelled to Flores Island for the memorial event referred to it as a potlach, Betty clarified it to be łaakt̓uuła (hach-tuu-kla), which means the “drying of the tears”.

“You’re not ready if you’re still crying. You’ve got to be strong to send them on their journey,” she said. “We’re crying inside because they died so young. But then we’ve got to be strong in order to have łaakt̓uuła, drying of the tears, letting them go on their journey, letting them go free.”

Numuch, Neil Keitlah, took a leading role in performing Nelson Keitlah’s songs for his nation at the event. After living in Vancouver for 14 years, Numuch moved to Ahousaht two years ago – with the expectation that he could bring his voice to the gap left when his uncle passed in 2016.

“The family asked me to be a part of taking out their dad’s dances,” said Numuch, admitting his nervousness as he awaited the chance to take up an eagle feather to lead the singers. “Last time I remember doing these dances was at my wedding over 20 years ago.”

He recalls Keitlah composing and practicing the songs in the privacy of his garage.

“Nelson, he raised me from the age of nine in our culture,” said Numuch. “A lot of Nuu-chah-nulth people, they’ve been waiting for my uncle’s dances to come out. They’re excited and I’m excited, it’s been a long time coming.”

Beyond the activity within the walls of the T-Bird Hall, for some it can be hard to believe that people have lived so close to the ocean’s fury for thousands of years, seeking sustenance from the surrounding waters while maintaining a complex society.

“Our ancestors, they were proud people. They knew how to survive, and that’s why we’re here,” noted Betty Keitlah. “They were in very close bond with the Creator. If they were in rough weather, there was really no shelter in that chuputs, the canoe, and they’d chant.”

“I think if you ask anyone that is from Ahousaht, they’ll say that’s where their heart is,” added Numuch. “It’s always hard to leave if you’re from here.”