On a crisp morning in early May, a group of teenagers from Port Alberni’s Eight Avenue Learning Centre were working the field in front of their school, realizing the garden they had conceived over the previous winter months.

Within a metal fence that had been erected a month prior, the Grade 8 and 9 class were measuring out where the garden beds would be made, while others carted loads of leaves to the site from a large pile that had collected behind the school.

Gracie Martinez and Gabriella Stanley were planning where raised beds would be installed. This is part of a design that used input from each student, recalled Stanley.

“Everyone drew one or two garden layouts,” said the Grade 9 student. “We got the measurements and everything, and then we went through and laid everything out. At the end we numbered all of them and said what we liked about each one and made this garden plan.”

“We all decided how everything was going to be laid out,” added Martinez. “We all scribbled down our own thing.”

The project is the result of research the students undertook over the winter, including methods to build garden beds and the importance of quality soil.

“I like learning about the soil health, how the different health of the soil will affect your plants,” Stanley remarked, looking over where raised beds will be built. “We’ll do cardboard, and then soil, then leaves.”

A vast quantity of leaves was collected from the surrounding neighbourbood over the previous fall. Smiles weren’t visible as the students gathered up and carted the piles of compostable material, due to the masks they were required to wear as a pandemic-era safety measure. But the exuberance of finally being engaged with the outside was evident.

“It’s way more fun than doing math inside,” commented Stanley.

“It’s actually doing something, it’s not just pointless questions for a mark out of 10,” added Martinez. “Instead out of 10, it’s how good is the garden.”

Kirsten Abercrombie has seen a growing eagerness among her students to plant things outside of the classroom.

“We spend so much time sitting and looking at screens these days, working outside feels great when you do it,” she said.

At a time when the day is dominated by cell phones, computer work and online meetings, school counsellor Karen Campbell sees the project as being a transformative activity for the students.

“It’s a COVID-safe way of being able to do a project like this. So many other school activities have had to stop,” she said. “There’s not a lot of leadership opportunity right now because of the pandemic. They are the originators of this space. As next year’s students come in, they’ll be able to show them all about the garden.”

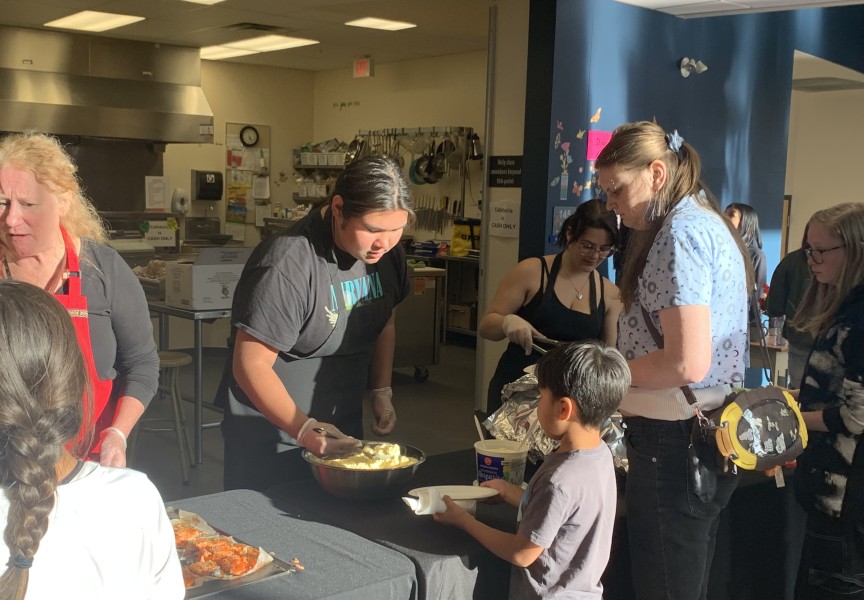

In the centre of the garden space lies a link to the surrounding area’s heritage. A large rectangle is designated for traditional First Nations pit cooking, a feature the school hopes to use in mid June for an outdoor gathering to celebrate the new garden. Following Nuu-chah-nulth protocol, the garden space received a blessing at daybreak on April 21, following guidance from a group of elders who are helping to retain ties to the ancestral past as the project progresses.

“It’s our Nuu-chah-nulth protocol to get that done in a good way, to get it all ready and prepared so things move forward in a good direction,” said Dianne Gallic, a Nuu-chah-nulth education worker at the school.

Besides the crops with a European influence, like potatoes and squash, the garden will contain some Indigenous plants that people in the area would harvest before colonization, such as huckleberries. But following direction from the elders, medicinal plants will not be grown.

“We’re not using any sacred medicines,” noted Gallic. “As protocol we have to respect that families have certain places where they find their medicines, we’re not about to start dabbling in any of that.”

After more than a year of restrictions on their formative lives, students are looking ahead to a project that will never stop expanding. There are even plans to manage the garden over July and August while classes aren’t in session.

“I live just down the street, so I can come and help out a lot,” said Martinez. “I don’t have room for a garden at my house, so this is the closest I have.”

“Every year there’s going to be a lot more work to get done,” added Stanley.