After months of negotiation, First Nations and DFO remain at loggerheads over co-governance of a proposed marine conservation area off the Island’s west coast.

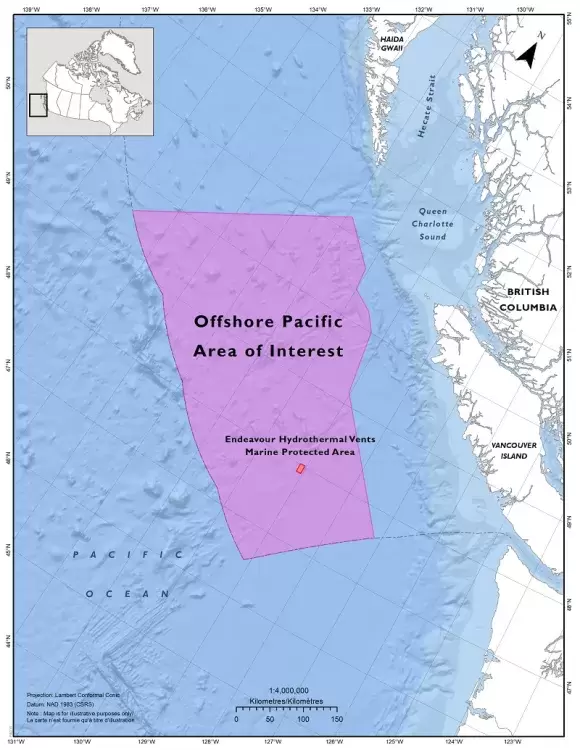

Talks between Haida, Quatsino, Nuu-chah-nulth negotiators and their DFO counterparts have continued for the past two years over the proposed Tang.ɢwan-ḥačxʷiqak-Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area, or what the federal government refers to as the Offshore Pacific Area of Interest (AOI).

The marine conservation area (MCA) — roughly 133,000 square kilometres or more than four times the size of Vancouver Island — would dwarf an existing one created in 2003 to protect the Endeavour hydrothermal vents.

While no one disputes the value of conservation, the designation could have profound implications for the rights and interests of coastal First Nations. Over the past year alone, negotiators have met 19 times, focused on drafting a memorandum of understanding that would establish a board and co-governance in managing the conservation area, but that essential goal remains a key sticking point. DFO refuses to budge, said NTC President Judith Sayers.

“What we want is a role in management and they just don’t want reconciliation, although they may be moving forward with that,” Sayers said.

Sayers said the federal government has expressed a desire to move ahead with the MCA expansion during its current mandate, but she questions the seriousness considering DFO’s rigid negotiating stance.

At a June meeting, ministerial staff wanted to publish the new designation in the Canada Gazette, giving it official status.

“They agreed not to do that because we had four main points,” in negotiation, Sayers said

Along with co-governance, First Nations want the management board’s scope of responsibilities to include decision-making authority in fishery matters as well as an agreeable dispute resolution mechanism.

In July Fisheries Minister Bernadette Jordan said the government is allocating $977 million in its current budget to continue marine conservation efforts and protect 25 per cent of Canada’s oceans by 2025.

“When we protect our oceans, we protect the coastal communities that rely on them,” Jordan said. “We know that healthy oceans have so much more to give. They feed more families, create more jobs. They help clean the air we breathe.”

The move is consistent with Liberal government policy since 2015, when less than one percent of Canada’s oceans was protected. Currently, the figure stands at 14 percent.

In an online discussion hosted by the conservation group Nature Canada, Jordan was asked to clarify the government’s commitment to the spirit of reconciliation and shared management of marine conservation areas.

“Is DFO mandated to engage Indigenous communities in this? How will it work with First Nations in oceans co-governance,” asked online host Gauri Sreenivasan of Nature Canada, conveying questions submitted in advance by Uu-a-thluk Fisheries Manager Eric Angel.

“That is part of the go-forward mandate,” Jordan responded. “I look forward to working with our First Nation partners in the development of marine protected areas. We all have a role to play and we’re going to make sure we do everything to uphold that … our First Nations are the stewards of the ocean space.”

Five of 14 existing MPAs are already managed collaboratively with Indigenous governments, including the SGaan Kinghlas-Bowie Seamount MPA in Haida waters. However, they fall short of true co-governance since any management decision may be overridden by the minister.

Sayers said they have not been advised by DFO if the new funding is intended for the Offshore Pacific AOI. There was no reference to it in Jordan’s July 22 funding announcement, but the government simultaneously released a report, The Current — Managing Oceans Act MPAs Now, For the Future. The report, intended to give five-year updates on MPA progress, points to a need to update policy and guidance to support First Nation participation, Angel noted.

Jordan agreed during the online question-and-answer session that there is a need to update legislation.

“We need a new approach for consolidating agreements like the Offshore Pacific Area,” the minister said, promising to strengthen community involvement and foster greater understanding of MPAs.

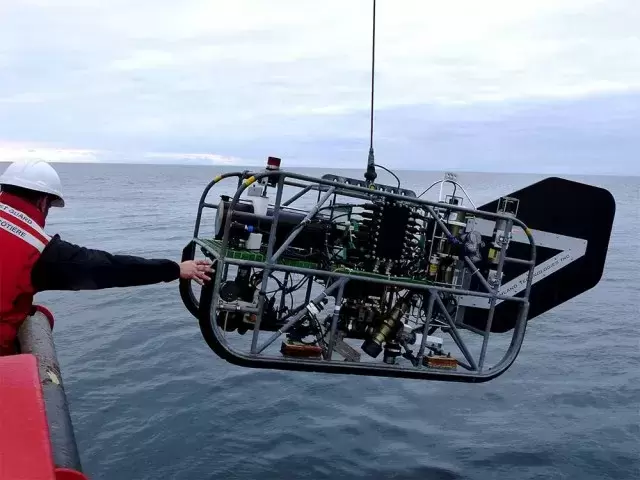

Toward the latter goal, NTC has been a partner with DFO, Council of the Haida Nation and Ocean Networks Canada in scientific exploration of seamounts off the west coast. Two years ago, Joshua Watts of Tseshaht First Nation and Aline Carrier, Uu-a-thluk capacity building co-ordinator, accompanied the annual voyage. Participation since then has been delayed by pandemic safety considerations.

“DFO science has been great to work with,” Angel said, attributing the negotiating impasse on bureaucratic resistance to power sharing.

An expanded MCA would be a step forward, but the designation has limitations as a conservation tool and no means of accounting for Indigenous knowledge within the existing legal framework, he said. Plus, there is a greater issue at hand that MPAs do not consider.

“They’re not really addressing why the oceans are in crisis,” Angel said.

Climate change was raised during negotiations but dismissed by government negotiators who maintain it lies beyond the scope of MPAs.

“It’s conceivable the you could set up an MPA that would be completely obliterated by climate change,” Angel said.

Seamounts are still the primary conservation focus of DFO’s Offshore Pacific Area of Interest, but they form only a small part of a much greater ecosystem, he added.

“Hishuk ish tsawalk,” Angel said, citing the Nuu-chah-nulth world view that everything is connected, everything is one.

“These ecosystems are worthy of study right up to the surface,” especially with the unsolved mystery of ocean mortality among salmon, he noted. “We’re wondering what happens to these fish when they go into deeper water.”