An opaque fog fills the Alberni Inlet on a chilly February morning, the milky hue spread through the surrounding city streets. By the water’s edge the beeping of excavators and trucks pierce the morning’s silence, the grumbling hum of their engines heard from an expanse of concrete running along the edge of the inlet.

Rusted, skeletal remains of a long unused sawmill operation are scattered across the 43-acre site, an area that has progressively been cleared by the city’s machinery over the preceding months. It’s the unfolding demolition of the Somass sawmill, an operation that a quarter century ago employed over 600 people, processing 500 long logs each day.

From the southern extent of the city to the mouth of the Somass River, the Somass mill was once among the major manufacturing facilities that lined Port Alberni’s waterfront, powering the city’s forestry-driven economy. But as the sawmill buildings are torn down, the future of the city’s waterfront appears to be headed in a different direction – one that municipal and First Nation leaders hope will honour both the community’s needs and the area’s history dating back before European settlement.

‘A fundamental shift for the city’

Since it purchased the Somass sawmill property in 2021, the city has pledged that the future of the land will be an entirely different chapter than its use over the past century. The City of Port Alberni bought the site for $5.3 million in 2021 from Western Forest Products, after the company had left the waterfront mill unused for years. This was clearly a case of the municipality forcing Western’s hand, as the sale occurred after the city gave an expropriation notice to the forestry company earlier that year.

“Acquiring the Somass Lands and adjacent parking lot has been a primary focus of city council since shortly after being elected in 2018,” said Mayor Sharie Minions in a press release at the time of the sale. “Remediating and repurposing these lands in a way that recognizes the shifting nature of our vibrant community represents a fundamental shift for the City of Port Alberni.”

Processing at Somass ceased in early 2017, leaving approximately 70 people out of work. At the time the mill specialized in cutting old growth Western red cedar, a tree that represents a foundational part of the heritage of region’s Nuu-chah-nulth people, who relied on the stands for their homes, textiles and tools for countless generations before the introduction of industrial-age materials. As voiced in the province’s Old Growth Strategic Review in 2020, a generational shift had occurred in British Columbia, leading many to view these old growth stands a something to be protected rather a resource to be profited from.

At the time of the mill’s shutdown WFP cited a lack of available timber as well as the need to cut costs amid a shrinking forestry industry. Then when the province released its budget the following February a 12 per cent decrease in harvesting over the following three years was forecasted, a production decline expected to result in 4,500 lost jobs out of the 50,000 that were employed in the forestry industry.

From mudflats to three daily shifts

Pictures of the Somass site from a generation ago illustrate an altogether different scenario, when neatly stacked piles of lumber filled the waterfront site, as the mill’s buildings churned out product around the clock over three daily shifts. According to MacMillan Bloedel’s figures, in 1989 the facility produced 114 million board feet, selling $64 million of wood product, with 70 per cent going to the United States and another 25 per cent of the lumber headed to Canadian markets. At the time 620 people were on the Somass payroll.

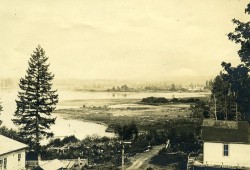

The mill was originally opened in 1935 by the Great Central Lumber Company, which had already been operating a sawmill facility on Great Central Lake. Initially specializing in hemlock and fir logs, the Somass mill took over the existing tidal mud flats, which were dredged in 1934 to prepare the ground for the new facility. The operation benefitted from the nearby railway’s transportation capacity, as well as the deep waters of the Alberni Inlet that could serve large vessels.

This all transformed the pre-existing landscape, which was part of where the Alberni Inlet transitions into the Somass River.

“That was all part of the Somass estuary,” said Sandy McRuer, president of the Alberni

Valley Nature Club, of the pre-existing mud flats, which were once “all flowing into this great flat area at the end of the inlet.”

The railroad and the later dredging of the mudflats also affected Dry Creek, which used to run directly into the Alberni Inlet over a century ago. Now the creek takes two sharp turns before reaching the inlet.

McCruer believes that the mudflats were once used by deer, bears, mink, otter, coon, heron and ducks, as the marshy land extended past to where the railway was built in 1911.

“The mud flats probably extended east of the tracks,” said McCruer. “A lot of that has been filled in.”

The location of a sacred ceremony

Very little is documented about the portion of the estuary where the Somass mill was built, but on either side of the site sat two important villages for the Tseshaht First Nation. Directly north, where the sprawling Catalyst paper mill now sits, was nuupc̕ikapis. Meaning ‘one tree on the beach’ and also known as Lupsi Cupsi Point, this site served as an important winter home for the Tseshaht.

According to archaeological and ethnographic investigations by Alan McMillan and Dennis St. Claire, in the 1800s the Tseshaht lived at nuupc̕ikapis as they migrated down the Alberni Inlet annually.

“By the end of November the main spawning runs were over and the Tseshaht congregated at nuupc̕ikapis, the present site of the pulp and paper mill, at the mouth of the Somass River,” wrote McMillan and St. Claire in Alberni Prehistory, which was published in 1982. “Margaret Shewish described a large complex of fish weirs and harbour seal traps adjacent to this village. Weir remnants are still visible at lowest tides along the Somass River near its mouth.”

nuupc̕ikapis is referred to as the main Tseshaht winter village at the time of European settlement in the late 1800s, but all important ceremonies done during the colder months were performed at ƛuukʷatquuʔis, or Wolf Ritual Beach, which was on the other side of the mud flats where Port Alberni’s Harbour Quay is presently. This village was where the ƛuukʷaana, or Wolf Ritual Ceremony, was held over 14 days. In June 2022 the historical importance of this village and the ceremonies it hosted were formally recognised at the Harbour Quay when artwork by Tseshaht member Willard Gallic Jr. was unveiled on a municipal landmark. What was formally the Clocktower became known as the ‘Wolf Tower’.

“Our ƛuukʷaana was a deeply sacred ceremony rarely spoken of and was organized by a person of high rank, usually it was a Ḥawił (head chief) who held this rank,” stated the Tseshaht First Nation in a document describing ƛuukʷatquuʔis.

At the time ownership of Tseshaht territory was governed by tutuupata, “a complex set of hereditary privileges or prerogatives,” according to the First Nation. This determined the use of economic resources, like fish trap sites, rivers and plant gathering locations, as well as intellectual property, such as names, songs, dances and regalia.

“The ƛuukʷaana was a deeply spiritual practice that helped prepare c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht) for their roles and responsibilities as a community member along with the way tutuupata (ceremonial rights) were communicated and shared to c̓išaaʔatḥ members,” stated the Tseshaht.

The result of expanded territory

The Tseshaht’s habitation at ƛuukʷatquuʔis and nuupc̕ikapis was the result of a period of great change for tribes in Barkley Sound. The First Nation estimates this to be between 1780 and 1815, a time marked by intertribal marriage and alliances, warfare and the incorporation of affiliated groups.

“The c̓išaaʔatḥ (Tseshaht) absorbed the maktlɁiiɁatḥ (maktl-ee-ahtah), našɁasɁatḥ (Nash-as-ahtah), hach`aaɁatḥ (Haa-chaa-ahtah), and hikwuulhɁatḥ (Hee-qulth-ahtah) who brought their nism̓a (lands) and č̓aʔak (waters) with them, as well as the once independent ḥaḥuułi (territories) of the original c̓išaaʔatḥ,” stated the Tseshaht on the First Nation’s website.

This greatly enlarged Tseshaht territory beyond the First Nation’s origins in the Broken Group Islands of Barkley Sound. The absorption of other tribes allowed the Tseshaht to migrate up the Alberni Inlet to benefit from the expanded territorial resources.

“Also in the late 18th century, the hikwuulhɁatḥ and hach`aaɁatḥ, today subgroups of the Tseshaht, jointly took control of the lower Somass River and its rich salmon runs at the head of the Alberni Inlet, displacing the unidentified inhabitants,” wrote McMillan and St. Claire. “The Tseshaht migration to the head of the Alberni Inlet did not result in the abandonment of their Barkley Sound sites, as these continued to be occupied for more than half of each year. Rather, it meant an expansion of their territory in order to exploit an even wider range of resource locations.”

By the late 1800s these territorial benefits were disturbed with the arrival of European settlements in the area. In the 1860s the Tseshaht were removed from ƛuukʷatquuʔis when the Alberni Valley’s first sawmill was established by Anderson and Company of London.

Displacement also occurred at nuupc̕ikapis, and by the 1880s a new federal system confined the Tseshaht to Indian reserves, as ordered under Canadian law. An account from Indian Agent Harry Guillod reported in 1884 that Tseshaht people “were much dissatisfied at not being able to get a reserve near the mouth of the river at Alberni. They are still on the mill company’s land, but have promised to move this fall.”

A ‘mixed-use’ site with public waterfront access

Now a new chapter lies ahead for Port Alberni’s waterfront and the land that was once between two Tseshaht winter village sites. In December the municipal government announced it had selected Matthews West to lead the development of a “mixed use site” with public access. For the last decade the development company has been working in Squamish, at the end of another inlet in Howe Sound. Currently under construction, Oceanfront Squamish encompasses 100 acres on the town’s waterfront, with space for a park, a campus, stores and 2,800 homes, enough for an estimated 6,500 people.

“Their proven track record and commitment to community input align perfectly with council’s vision for this waterfront property,” said Port Alberni Mayor Sharie Minions in a press release. “Together, we will create a mixed-use site that provides public access to the waterfront, generating a vibrant waterfront community for residents and visitors to enjoy.”

Another benefit to Matthews West is their close work with the Squamish Nation in the oceanfront development and the Cheekye Fan project, which is designed to bring over 1,200 homes to the First Nation’s land, with accompanying trails and commercial space.

The company aims to do similar work at the end of the Alberni Inlet.

“We see tremendous opportunity for growth in Port Alberni due to its attractiveness as a recreational centre that offers natural beauty, lifestyle and a strong sense of community,” said Matthews West President John Matthews in the city’s press release. “We look forward to the upcoming work on the site, engaging with the community, and working hand-in-hand with the Tseshaht and the Hupacasath First Nations on this exceptional development opportunity.”

Amid the carnage of yesteryear’s industrial giant, 90 per cent of the Somass sawmill’s structures have been diverted from the landfill by being recycled, reused or sold, according to Scott Smith, Port Alberni’s director of development services.

But the extent of ground contamination from over 80 years of operations has yet to be disclosed.

“The property was a former industrial site for many years,” said Smith in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “The city has received grant funding to begin remediation of the property and further remediation will continue in partnership with Matthews West.”

Not all structures from the mill site will be disposed.

“Two buildings are currently being kept in order for Matthews West to assess the feasibility to repurpose them as part of the future development of the property,” said Smith.