Undertaken by the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council in partnership with Simon Fraser University and the National Microbiology Lab, the multi-year study has just completed its initial analysis of data collected from over 1,000 people, comprising roughly one tenth of the Nuu-chah-nulth population. With an emphasis on maintaining collaborative agreements with 14 Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations, the study drew upon 1,040 surveys and 851 blood samples that were voluntarily given, with 416 participants taking part in “talking circles” to provide insights into how people responded to COVID-19 and its vaccinations.

“Over time, as new versions of the virus emerge, the blocking ability of antibodies decrease,” states a report on the study. “Getting boosted with updated versions of the vaccine can increase/improve protection from new versions of the virus.”

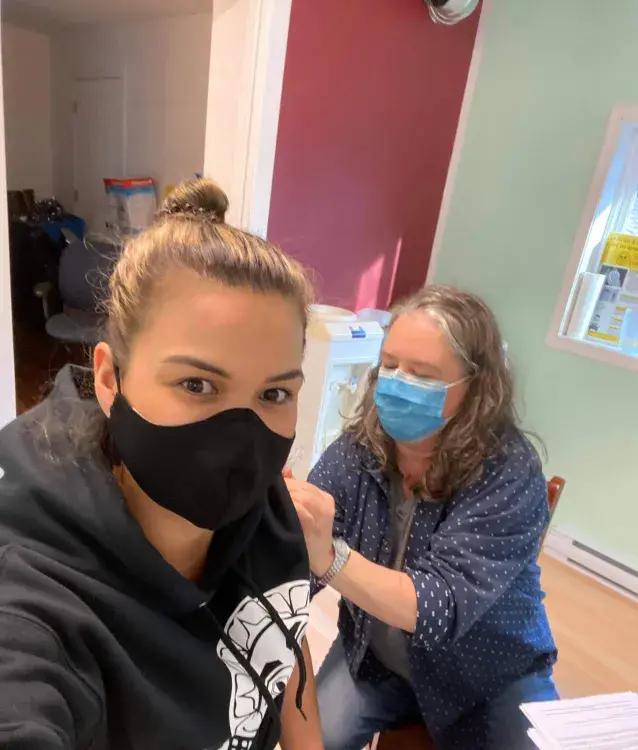

In the early stages of the pandemic, Indigenous people were deemed to be at a higher risk from COVID-19 than the general population – particularly among those in remote communities with limited access to medical care. For this reason, residents of coastal Nuu-chah-nulth villages were among the first in British Columbia to get vaccinated when teams of health care workers brought in thousands of Moderna doses in January 2021.

Two years into the pandemic, the approach appeared to be working. As of April 2022, data from the First Nations Health Authority listed over 21,000 Indigenous cases in the province with 258 deaths, statistics that align with B.C.’s general population.

But not all Nuu-chah-nulth people were comfortable with getting vaccinated. Results from the NTC’s COVID study show that 82 per cent of participants got at least two shots to be fully vaccinated, while nine per cent received no shots at all. This is close to B.C.’s 85.55 per cent rate of full vaccination, which shows 57 per cent of the province with three or more COVID shots.

The rate of additional vaccination also declined among Nuu-chah-nulth, according to the study, as 30 per cent of participants had three shots, 14 per cent indicated four and just five per cent received five or more doses of vaccination.

In September 2021 the province began introducing vaccine mandates for health care workers and other sectors, with the requirement of full vaccination to visit restaurants or enter certain public facilities. In most cases, this did not apply to additional doses beyond the two that were initially required.

Dr. Roger Boyer II is the COVID study’s director of research. From the project’s talking circles it was evident that a handful of people had a strong distrust of the government’s use of the vaccine.

“They were just very hesitant,” said Boyer. “They were wondering what was in the vaccine. Were we just guinea pigs? Were they testing us again?”

Input gathered over the course of the study indicated fears of trusting a vaccine with unpredictable side effects that could cause long-term reactions. Boyer heard from some participants that didn’t want to get “re-traumatized”.

These concerns were evident among some residential school survivors who participated in the study. Boyer heard from one former student of Christie Indian Residential School who still has 14 scars over the middle of the spine due to testing during childhood.

“All those types of re-traumatizations would come up, and the questions and conspiracies,” he said. “Their big concern was, ‘We don’t know a whole lot about this virus, we don’t know a whole lot about the vaccine, and now we are a test population for Moderna’.”

But as COVID-19 has stepped away from the spotlight of public health concerns, some in the healthcare profession fear the pandemic has left a sour hesitancy towards vaccines that could impact other diseases. This became evident during sessions Boyer held with NTC nurses as part of the COVID study.

“Is there going to be a rise in the community of other viruses that once were not here anymore?” said Boyer of the concerns he heard from nurses, which pertains to polio, measles, mumps and rubella. “These are the standard vaccinations that kids usually get. Are parents now making the choice to not vaccinate their kids, which is a huge public health herd immunity issue?”

COVID-19 brought heightened concerns of infection in remote Nuu-chah-nulth communities, where households are often large in close quarters and access to medical facilities requires a several-hour excursion. This brought a wave of lockdowns along the west coast of Vancouver Island, with access limited to residents and healthcare workers. Exit from the communities was often also restricted to one person per household to undertake grocery runs and other necessary trips.

But this didn’t bring lower infection rates, according to the recent COVID study, which shows little difference between urban and “at-home” Nuu-chah-nulth-aht. Fifty-five per cent of those who participated in the study tested positive for COVID-19 at some point, with a 66-per cent rate from the northern region. This region includes the Ehattesaht village of Ehatis, located next to Zeballos, which is a two-hour drive from the closest hospital in Port Hardy. In December 2020 Ehatis encountered 28 cases, comprising over one quarter of its on-reserve village, presenting an outbreak that other Nuu-chah-nulth settlements feared. Fortunately, there were no fatalities.

Over the course of the study input and samples were collected from 37 Nuu-chah-nulth communities, as well as Port Alberni, Nanaimo, Campbell River, Victoria, and Vancouver.

Across this wide region, 48 per cent of those in households with two or three people got infected, while people who live alone had a higher rate of 62 per cent.

“We assume that they had to fend for themselves, go out and get their own groceries, go do their own services during that two-year time,” said Boyer of those who live alone.

But larger households recorded a higher rate of infections that reached 70 per cent of those surveyed.

“People who had four or more living in their household, that’s where the majority of the positive self-reporting testing came from,” said Boyer.

“We can, with some confidence I would say, determine that a joint effort, a joint pandemic plan across the regions would be beneficial,” he added. “The strategies around vaccination were strong, the strategies around isolation were effective, the communication in the communities was beneficial - but when it comes to the virus there were no unique strategies that nations put in place that had an impact on COVID or the COVID virus.”

For those who provided a blood sample for the project, individual results are now available. These can be provided within 10 business days by giving your legal name and date of birth to covid19results@nuuchahnulth.org.