Despite growth in herring populations, Nuu-chah-nulth leaders remain concerned about the long-term health of the species, opting again to not permit a commercial catch in 2025.

But for the first time in several years, a spawn-on-kelp fishery is being planned by Ha’oom. Owned by Ahousaht, Ehattesaht, Mowachaht/Muchalaht, Hesquiaht and Tla-o-qui-aht, the fisheries society hopes to capitalize on commercial opportunities in selling herring roe, or k̓ʷaqmis, attached to kelp in their respective territorial waters.

The volume of herring tracked on the B.C. coast has risen significantly in the past few years, a rebound from historic lows seen over a decade ago. On the west coast of Vancouver Island the calculated biomass has risen since being under 15,000 tonnes in 2018 to 65,500 this year. Almost 60,000 tonnes are expected to be off the west coast of the Island in 2025.

Reproduction has shown an even more marked increase, based on models that calculate herring spawn. Since 2015 the herring spawn index has risen from under 12,000 tonnes to over 86,300 this year, the largest seen on the west coast of Vancouver Island since the mid-1970s. Over the last few years the region’s most concentrated spawn has been in Hesquiaht, but in 2024 larger volumes were seen in other areas along the west coast. Herring spawn data from Fisheries and Oceans Canada shows 31,152 tonnes in Barkley Sound, 39,700 in Clayoquot Sound and 15,420 tonnes in Nootka Sound in 2024.

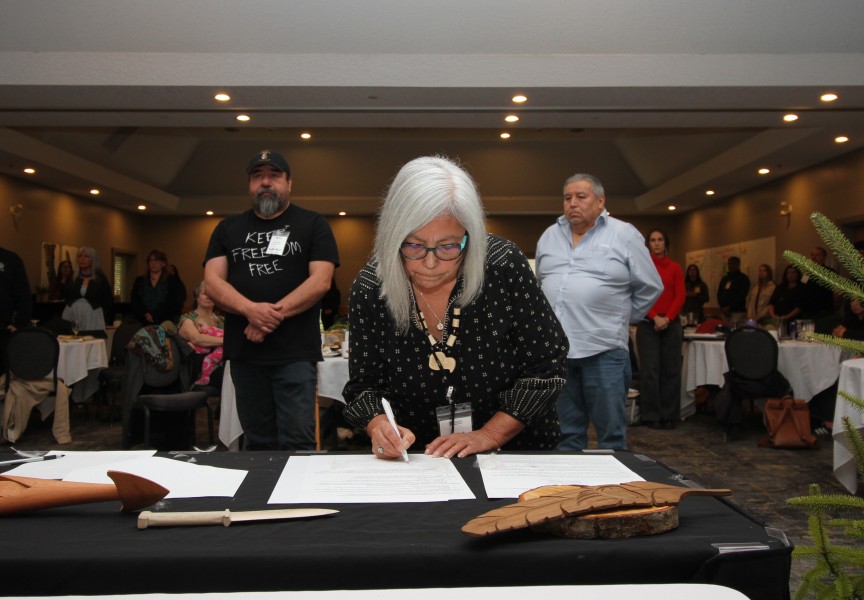

In late October DFO sent out a draft Integrated Fisheries Management Plan to various stakeholders to determine if and how much herring will be caught in 2025. The recent population numbers are well above the upper stock reference point, which is an average of the herring volume tracked in the 1990s that sets a benchmark for conservation considerations. But this did not sway the views of Nuu-chah-nulth leaders, and at a meeting in early November the Council of Ha’wiih Forum on Fisheries voted to keep the commercial seine and gillnet herring fishery closed for another year on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

“Ahousaht’s position is no, no fishery at all,” said Andy Webster, a lifetime fisherman who represented Ahousaht at the recent meeting, which was hosted by the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation Nov. 5 and 6 in Tsaxana. “Just because we see some big spawning in Clayoquot Sound doesn’t mean there’s a lot of herring. There are spawning beds that are still inactive. Until such time that I see activity in the other ones, I think it should remain closed.”

Tla-o-qui-aht Fisheries Manager Andrew Jackson expressed concern that a full-scale commercial herring fishery could reverse the recent population rebound.

“We’re happy to see it, we’re a little bit leery of harvesting activity in that they’re going to disappear again,” he said. “We don’t even have enough herring in our nation’s Ḥahahuułi for us to even have a food fishery.”

At the end of winter each female herring lays thousands of eggs that stick to underwater rocks, silt and kelp, awaiting the milky spawn from males – reproductive activity that turns parts of the ocean a lighter aquamarine colour. Traditionally, Nuu-chah-nulth-aht harvest this roe by dipping branches in the waters thick with herring eggs, bringing up the beloved k̓ʷaqmis. But in recent years many Nuu-chah-nulth nations have had to buy this delicacy from other Indigenous communities on the central coast of B.C.’s mainland.

It was just two years ago that Ahousaht could once again harvest an adequate supply of k̓ʷaqmis from its own territory, said Webster.

“For all the years that we went without, our people had to buy from Bella Bella,” he said. “A young fellah used to come down and sell them by the buckets to the people that wanted to buy, at a big expense to our people.”

“Most of our k̓ʷaqmis still comes from the central coast,” said Nuchatlaht Councillor Archie Little. “We’re not anywhere close to what we had. Nuchatlaht had herring and k̓ʷaqmis all year round, not just to feed when they’re spawning.”

Jackson said Tla-o-qui-aht won’t support a commercial herring fishery until members can get thick roe from their shores.

“We wouldn’t support until we see an adequate number back where our people can go and harvest at our front door, like we used to right in front of Opitsaht,” he said. “Stubbs Island, from Tofino to Opitsaht, used to be white when I was a teenager. The whole thing was white with spawn.”

The west coast of Vancouver Island hasn’t seen a commercial herring fishery since 2005, which was followed by years of the region’s biomass wallowing under 10,000 tonnes. Elsewhere on the B.C. coast, an annual commercial catch has usually only taken place in the Strait of Georgia, held for a few weeks each spring with the aim of catching females while they are full of eggs. The roe is exported, mostly to Japan, while the herring fish are ground down into feed for livestock and fish farms. In 2022, $19 million of herring product was sold to Japan, comprising 71 per cent of the total value of the fishery’s exports from B.C., according to DFO reports.

Another lucrative part of herring fishing is spawn-on-kelp, most of which is also exported to Japanese markets. In 2025 the Ahousaht, Ehattesaht, Mowachaht/Muchalaht, Hesquiaht and Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations plan to tap into this commercial opportunity through the operations of its Ha’oom Fisheries Society.

“Because the stock has increased, it has been proposed by the five nations to potentially engage in a fishery of low impact, which is the spawn-on-kelp fishery,” said Kadin Snook, Ha’oom’s fisheries coordinator.

Snook said that licences would potentially permit the nations to harvest 16,000-48,000 pounds of the product from Feb. 1-April 30.

“This fishery is going to be a community-based, five nations fishery,” he said. “If successful, it will provide necessary revenues, and more importantly, information on how the kelp spawn densities are doing.”

A recent letter from the Council of Ha’wiih to DFO stated research indicates that 78 per cent of herring that come into contact with a spawn-on-kelp operations survive, compared to none that are affected by seine and gillnet fisheries.

“I see this as a great opportunity, it hasn’t been done since the early 2000s, I think,” said Ahousaht member Richard Little, noting the urgency to prepare the necessary equipment for when kelp blades are thick with herring roe in a few months. “To make this work, we’ve got less than 100 days between now and mid-February when the herring is going to come into Sydney Inlet.”

The Integrated Fisheries Management Plan for Pacific herring is collecting input until Dec. 3. An approval from Diane Lebouthillier, Canada’s minster of Fisheries and Oceans, expected in early January.