This story starts down an abandoned forest service road deep in central Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations territory on Vancouver Island. It was fall, two or three years ago. Tyee Wilson Jack was bucking up a log for firewood when he saw something move on the right side of his periphery.

“Did something just stand up?” thought the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ (Ucluelet First Nation) Hereditary Chief. “I didn’t want to turn my head, but I moved my eyes. I swore. It’s a frickin’ Pookemis.”

“He’s just watching me,” Jack thought as he continued chopping, as he said to himself, “I’m not gonna panic. One more swing and I’m gonna look.”

“THWACK!”

Jack swung his axe then turned his head to look. The creature jumped off the stump it was standing on and hid.

Jack said he heard the jump and saw the bookemis – or Sasquatch as the bipedal hairy giant is commonly called – for one second from about 25 metres away.

“The hair on the face is long. The eyes are really dark and glassy, I guess. It was tall. Just the way I saw it stand up. It was like easily over seven feet. It was big. And the smell it left was stench,” Jack recalls.

Jack says elders always taught that if someone has an experience with a bookemis, they should leave it an offering.

“I left six pieces of chopped wood. I yelled, ‘I’m leaving you this wood’.”

The next morning, bright and early, Jack returned to the site of the encounter and the wood was gone – but there were huge footprints.

“I didn’t take any photos, damn it. I didn’t think to bring my phone,” said the 58-year-old.

Jack shared other stories too; of MacMillan Bloedel loggers hearing them in caves, a woman bumping into one in the Hitacu village at night and on one occasion, when he did have his phone, Jack recorded a deep, grunting noise.

He played the recording for two conservation officers he met while hunting in Nahmint one winter.

“They looked at each other. They’d never heard the sound before,” said Jack.

“What is it?” asked the conservation officers.

“You won’t believe me if I tell you. It’s a pookemis. A Sasquatch,” Jack replied.

200 black bears for every Sasquatch

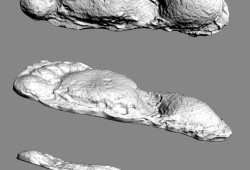

Cynical unbelievers might be swayed by the ongoing research of Dr. Jeffrey Meldrum, professor of anatomy and anthropology at Idaho State University. Dr. Meldrum has dedicated his life to studying Sasquatch tracks or Anthropoidipes ameriborealis (North American ape foot).

Meldrum’s primary evidence includes the analysis of hundreds of footprint casts. His research has been published in the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, the Journal of Scientific Exploration and he has penned several books on the man-like creatures, including ‘Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science’ and the ‘Sasquatch Field Guide’.

“I’ve examined long trackways. That’s what pulled me in was examining a long trackway of 35 to 45 tracks that showed all the variation. It showed toes extended, toes flexed, toes sliding in the mud, half tracks where it was running up on the front half of the foot, all the dynamics of an animate foot,” Meldrum told the Ha-shilth-sa over a Zoom call.

He says the hoaxes are “very transparent” and that anyone with a little wherewithal and familiarity with the anatomy and functional aspects of the primate and human foot could distinguish a real track from a fake.

“Finding a long line of tracks with successive tracks is really rare,” Meldrum said. “My privilege of looking at a long line of tracks was actually quite unique. I was so floored because at that time I was kind of ambivalent in my attitude towards the subject matter. I was intrigued, but ambivalent and very skeptical.”

He admits that the lack of physical remains is frustrating, but not surprising given the moist forest habitat, acidic soils, and the presumed intelligence and caution of the trackmaker.

“It’s the favourite piece of missing data the skeptics focus on and obsess with it to the exclusion of everything else,” said Meldrum, who has faced criticism from his peers for decades due to the absence of fossil records.

With the recent discovery of fossils from a small extinct hominin species labeled Homo floreiensis (hobbit) on the Indonesia island of Flores, Meldrum says the scientific community is “at least tolerating the possibility that Sasquatch might exist”.

Based on credible sightings and footprints, Meldrum says that there is good evidence to suggest that the Sasquatch is a large, powerful omnivorous species that has similar habitat requirements to black bears.

“The ratio, I think, is about 200 black bears for every one sasquatch. That’s not just pulled out of the air. That’s based on inferences drawn on about analogy of their social structure, their size, the life history of great apes and so forth,” said Meldrum.

“The point being, have you ever talked to anyone who has found a black bear skeleton in the woods?” asked Meldrum.

The professor of evolutionary biology went on to compare the supposed social behaviour of Sasquatch to orangutans – male orangutans are primarily solitary and communicate with loud calls to advertise their presence and attract a female.

“I think that is probably a good analogy for sasquatch because we have those ruckus loud calls,” said Meldrum.

The smoking gun?

In May 2023 Darby Orcutt, the director of Interdisciplinary Partnerships at North Carolina State University Libraries, launched a “curiosity driven project” approved by the Institutional Review Board called the ‘Study of Allegedly Morphologically Anomalous Physical Samples’. He put an open call out to anyone in the United States or Canada with unusual samples to offer for deeper analysis and genetic testing.

Orcutt says they received more than 100 items to investigate, including hair, teeth and even body part his research team informally dubbed a “hand-paw thing”.

“The DNA is really the gold standard today. It wouldn’t matter how wonderful the trace evidence of apparent trackways were - that’s never going to be what puts the scientific community or the general public over the top. But DNA…well, that’s a different matter,” said Orcutt over Zoom.

“If we were to find something interesting, that would really change the understanding of this topic. But that all depends on IF there is a biological species underlying this phenomenon and IF someone offers an authentic sample of it,” he said.

The Bigfoot Field Researchers Association sent Orcutt a cache of hair samples to work with.

“It’s a sacred trust, really,” said Orcutt. “Real science takes a lot of time. We are batching this up and very meticulously documenting each one.”

Unfortunately, Orcutt says the first analysis of 20 samples did not yield results, so they are using a different approach.

“The samples are not the freshest,” he said. “There is tremendous opportunity for Indigenous communities to partner on this.”

The Bigfoot DNA study remains open to any offerings of unidentified specimens found in North America. Folks who submit samples can be identified by name or opt to keep their identity confidential.

“The other thing is, we are not disclosing specific locations of things at all. We’re not doing that under any circumstance. We might say, ‘This sample came from Saskatchewan or eastern Kentucky’. That’s about as specific as we’ll get,” Orcutt promised. “It’s kind of like fishing. We don’t want to reveal their hiding hole.”

Orcutt went on to say that if they do find an undiscovered species, they will be “careful and ethical with the reveal”.

The ‘hide-and-seek-champion’

Nuu-chah-nulth have many stories about seeing Sasquatch and unique names for the creature.

Huu-ay-aht First Nations knowledge keeper Qiic Qiica says the belief in Sasquatch, or C̓ac̓uqḥta, is widespread and deep rooted in his culture.

“Our people, historically, were always hunters. In Nuu-chah-nulth culture, there are a number of animals that we just don’t hunt. One of them is C̓ac̓uqḥta. Another one is the wolf, we don’t hunt them because they are a pack animal, we believe they live like us. Same with the orca,” Qiic Qiica said.

“Another one we didn’t used to hunt is the black bear. In the plains or on the mainland, you might hear of Indigenous people who would eat bear, our people never did because it was believed they were like the healer or the doctor. They could have anything wrong with them and they know what to eat to fix it,” he explained. “Our people used to watch the bear to learn what they eat for getting better.”

Qiic Qiica points out that the greatest predators in North American are rarely seen.

“More often than not, they see us and we don’t see them. Think about how illusive the wolves are, how illusive the cougars are. Those are some of the most illusive animals in the world. From our point of view, the C̓ac̓uqḥta is even more illusive than the most illusive. It really is the hide-and-seek champion.”

He shared a story about an ancient agreement between C̓ac̓uqḥta and a Huu-ay-aht chief that teaches about protecting its identity:

The Chief got really curious about it and he kept trying to go out and find. He would go out when it was foggy, he would go out at daybreak or dusk and try to find it. He went out this one foggy day and he could see in the distance C̓ac̓uqḥta. He started following it, chasing it and trying to see where it lived.

Finally, the Bigfoot realized he was being followed so he started running. The Chief was trying to keep up to it and he ended up slipping on a rock and hurt himself. The Sasquatch turned back and felt sorry for him. He wanted to help him. The Chief was really grateful because he was saved by this creature and he asked him, ‘What do you want in return?’

The Sasquatch replied and simply said, ‘I want to be left alone.’

It’s a spiritual gift to encounter a Sasquatch, according to Nuu-chah-nulth culture.

“If you are so blessed to ever see one or be in the presence of one, you were chosen,” said Qiic Qiica.

Jack echoes the sentiment.

“It’s not there to harm you. To me, it’s a protector. They’re just curious. I would never recommend anyone to harm it. I would hate to see anyone harm something like that,” he said.