A change in Ottawa appears likely this year, leaving some to wonder what place reconciliation will have in Canada’s next government.

With a federal election expected this spring, the Conservative Party of Canada is riding high in the polls, making Pierre Poilievre the most likely candidate to become Prime Minister. Under the leadership of Justin Trudeau, for the last decade the Liberals have tripled spending on Indigenous services compared to 2015 dollars, but the Conservatives have made so such commitment.

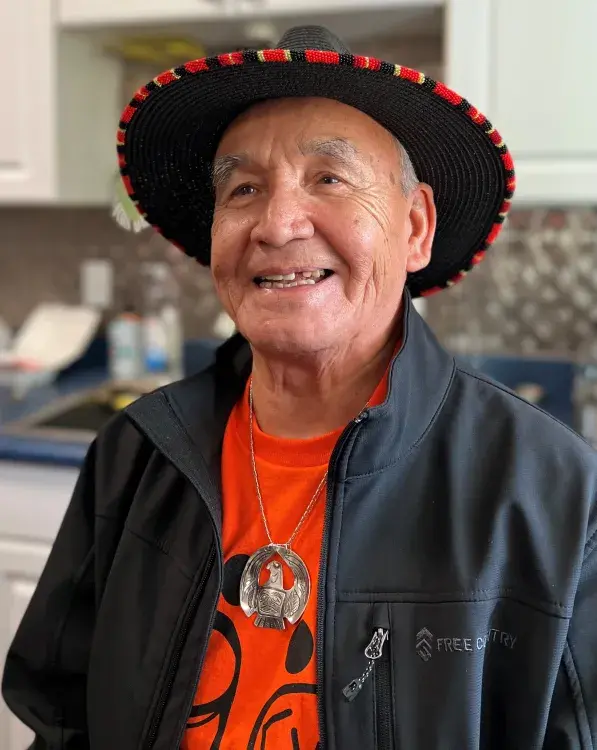

“The whole world is moving to the right politically, which to me is scary,” commented Tseshaht elder Randy Fred. “My fear is going backwards. We’ve made so many advancements in reconciliation, but they can all be destroyed quickly.”

“We’ve got to do as much as we can to avoid politics getting us down,” added Fred, whose traditional name is Wickee Cussee.

As the elder in residence at Vancouver Island University, Fred seeks to bring a message of inclusion and optimism to an upcoming talk on Jan. 23 at Campbell River’s North Island College campus. As in all of Fred’s talks in his current role, a foundational message comes from the Nuu-chah-nulth phrase that means ‘everything is connected’.

“That’s what reconciliation has the potential of doing, is making the entire society appreciate Hišuk’ish c̕awak,” explained Fred. “It means coming to terms with the past and moving forward in a positive way together.”

The Tseshaht elder has found a keen audience for this message among VIU students – particularly those who originate from other countries.

“A lot of them are coming from colonized countries, they know what colonialism is, and they can see it here,” he said.

Fred’s life has brought a great deal to come to terms with. He spent his early childhood at Dodger Cove, by Diana Island in Barkley Sound.

“It was paradise back them,” recalled Fred. “At the sandy beach at the far end there was a bed of little neck clams. I used to eat them raw for a snack, they were really tasty.”

But like so many Indigenous people of his generation, government policy relocated Fred from his family to attend the Alberni Indian Residential School, where he remained for nine years. It was a harsh contrast to living with family by the waters near Bamfield.

“My introduction to non-native people was these horrible sadists, these sick, sick people who were responsible for our lives 24 hours a day,” said Fred of those who worked at the residential school. “It was certainly not healthy. It destroyed our people, destroyed our communities, destroyed our families.”

Despite this hardship, Fred became educated as an accountant, bringing this skill in numbers to the team that returned to AIRS to shut the residential school down in 1973. The West Coast District Council of Indian Chiefs soon took over the facility.

“We gave them 30 days notice…and then we moved in. We took over the buildings to set up our tribal council office,” said Fred. “You live with this inferiority complex from just being in the school. And then to boot these people out…”

Whether he was looking for work or trying to check into a motel, encounters with racism would continue through the years. Fred finds that it’s still present, although society has improved over the last decade.

“I haven’t encountered much racism in a last 10 years,” he said. “True reconciliation will never take place, because we will never get all of our land back. But regardless, we have to move forward in a way that is putting this society on a more positive basis than how it is today.”

A foremost matter of concern is management of West Coast fisheries and their dwindling salmon stocks – a resource that Fred’s people have subsisted on for countless generations. In Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s current management plan for Pacific salmon, the federal department states a commitment “to the recognition and implementation of Indigenous and treaty rights related to fisheries, oceans, aquatic habitats and marine waterways”. DFO adds that this commitment aligns with Canada’s Constitution Act and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, noting that “reconciliation informs the work of the department”.

But the central issue remains that the DFO will not surrender control of fisheries, says Fred, and recognize that local First Nations were stewards of the resource for centuries before European settlement. He looks south of the border to a decision in Washington State from Judge George Boldt in 1974, which affects treaty nations of the Pacific Northwest. Boldt determined that these tribes have the right to half of the catch, with the equal responsibility to manage fisheries with the government.

“I’m certain that if the First Nations were to be given management control, that there would be a lot of habitat restoration going on,” said Fred. “Historically, it’s almost like they’ve been our enemy. Reconciliation to DFO needs to be taken really seriously. We’re not the enemy; we own the resource. DFO has to admit that and start acting in a responsible manner and enable First Nations to take an active role in management.”

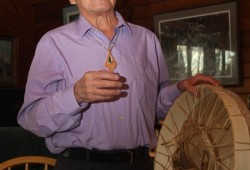

Fred suffers from reconitis pigmentosa, a hereditary disease that caused him to lose his eyesight as an adult. When working as an accountant was no longer possible he started writing and publishing, founding Theytus Books and the One in Spirit Healing Arts Society.

Now 74, Fred learned to find his way around in the dark when he was five years old, paddling his family’s canoe as they travelled at night.

“I always had night blindness,” he said, a condition his parents were aware of. “They knew I couldn’t see in the dark. A lot of times we would travel at night in the canoe, and they would make me row. I became a really good rower. Having to get around in the dark was a real big bonus for me today.”

Randy Fred speaks as part of North Island College’s Indigenous Speakers Series. His talk is on Jan. 23, 6 - 8 p.m. at NIC’s Q̓ə pix ʔidaʔas Gathering Place at the Campbell River campus, 1685 South Dogwood St. On Jan. 25 Fred joins author Celia Haig-Brown at the Museum at Campbell River from 1 – 3 p.m. for a talk about their work and incorporating First Nations’ history and culture into writing.