The Ministry of Health has announced 26 new substance-use treatment beds, additional capacity that is expected to help 250 people over the next two years recover from addiction.

But none of these beds will be in western Vancouver Island - despite the fact that in September the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council declared a state of emergency due to overdose and mental health crises. The new spaces that have become available since last summer include six in Kelowna, two in Prince Rupert, 12 at the Salvation Army’s Harbour Light Centre in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and another six at Nanaimo’s Island Crisis Care facility. These add to B.C.’s supply of over 3,700 publicly funded substance-use beds.

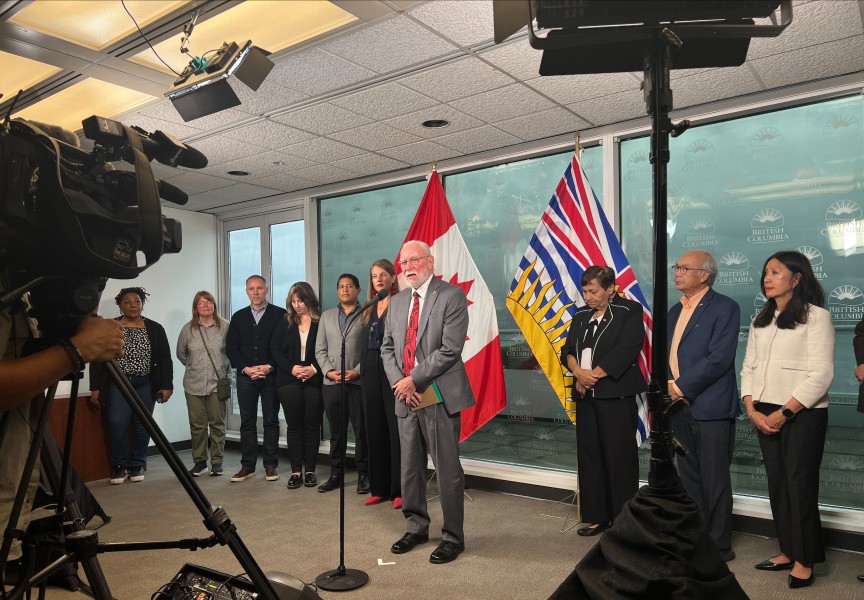

When the new beds were announced on Jan. 20, Minister of Health Josie Osborne acknowledged the toll that the opioid crisis has made on Nuu-chah-nulth communities, noting that she plans to meet with NTC President Judith Sayers this week to discuss the issue.

“Many people are trapped in a cycle of addiction and they feel that there is no way out,” said Osborne, who is also the NDP MLA for Mid Island-Pacific Rim. “For those who need help, it’s often even harder because of the barriers that stand in the way of them getting the treatment that they need.”

During the NTC’s Annual General Meeting in November it was noted that a consultant has been hired to better determine the specific needs of the tribal council’s 14 nations, while obtaining more precise numbers of how many have been lost from each community. The NTC’s state of emergency came after the Ehattesaht First Nation made its own such declaration in February 2023 due to the high number of young members lost over the previous year due to drug overdose.

Across the province, Indigenous people have been hit with a fatality rate six times that of the rest of B.C., according to the First Nations Health Authority. Since the provincial government first made the opioid crisis a public health emergency in 2016, death due to illicit drug use has risen to surpass homicide, suicide and car crashes combined. Fentanyl is detected in over 80 per cent of fatalities.

An average of five people die due to illicit drug use each day, according to the most recent data from the BC Coroners Service. But this is the lowest toll since the early days of the COVID 19 pandemic, which brought a surge in overdoses as public health measures encouraged people to stay home and socially distance from each other. Over the first 10 months of last year 1,925 fatalities have been attributed to overdose – showing a nine per cent decrease from the same period in 2023.

According to the most recent coroner’s data from last year, Vancouver Centre-North - a local health area that covers the Downtown Eastside - continues to have by far the highest rate of fatality with 409.7 deaths per 100,000 people. Terrace is second with a rate of 150.4, followed by Campbell River with 127.7 deaths per 100,000.

This data was tracked until August of later year, a period showing a significant decline in the fatality rate for Alberni-Clayoquot, a local health area containing a high proportion of Nuu-chah-nulth people. Last year Alberni-Clayoquot was the third highest in B.C., behind the Downtown Eastside and Hope, but so far numbers from last year show a rate dropping from 105.9 in 2023 to 77.8 per 100,000 people in 2024.

Some may take encouragement from these numbers, as B.C. enters the final year of a three-year decriminalization pilot project that began in late January 2023. Health Canada has granted B.C. an exemption under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, freeing users from facing charges if found in possession of up to 2.5 grams of the most common illicit substances, including Fentanyl, cocaine and methamphetamine.

Decriminalization was introduced to free users from the societal stigma they face, thereby enabling them to more easily seek help. But after a year this approach faced a growing amount of criticism amid reports of public drug use – particularly in hospitals.

“We refuse to accept addiction as a lifestyle choice,” said Conservative Party of BC Leader John Rustad, who called decriminalization “a failed experiment”, as an election approached last fall.

In a move to scale back policies, in May 2024 the government again prohibited illicit drug use in public spaces.

With the new government that formed after the October 2024 election, the former Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions has been absorbed into the larger Ministry of Health.

At the Jan. 20 press conference Osborne assured the public that the overdose crisis remains one of the top concerns for the province.

“Substance use is a health issue, and it needs to be treated as such,” she said. “Having the mental health and addictions ministry move back into the health ministry ensures that we are able to be as efficient as possible with a really fantastic team who are devoted to tackling this crisis.”

In an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa, the Ministry of Health stated that future treatment of the opioid crisis will be guided by A Pathway to Hope, a long-term plan for the province first introduced in 2019. This 10-year vision for addictions treatment stresses the need to improve access to mental health supports, with the expansion of Aboriginal-run treatment centres and better access to counselling.

“This crisis remains one of the top priorities that our government is committed to tackling,” said Osborne. “Beyond that, it’s about the early intervention and prevention, working with youth that have mental health issues, to avoid these problems in the first place.”