Despite being the urban hub for a region with the highest fatal overdose rate on Vancouver Island, there are no detox beds in Port Alberni.

This summer the BC Coroners Service released data on drug overdose deaths for the first half of 2025, numbers that put the Alberni-Clayoquot local health area fourth in the province for the rate of fatalities. Comprising almost 36,000 residents, this health area includes Port Alberni, Tofino, Bamfield and all communities in between, where a fatality rate of 74.1 per 100,000 was tracked from January until the end of June 2025.

Above Alberni-Clayoquot are Quesnel, Terrace and Vancouver Centre North, an area of the city that includes the Downtown Eastside. Considered to have one of the highest concentrations of illicit drug use in North America, the DTES health area posted a fatal overdose rate of 310, far outpacing anywhere else in the province.

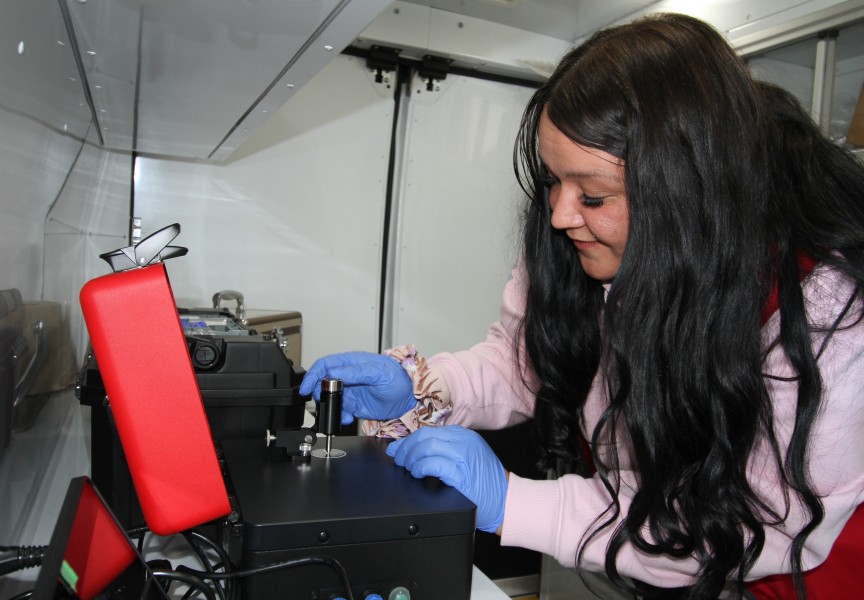

As a harm reduction coordinator with the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Brianna Rai works personally with illicit drug users every day on the streets of Port Alberni. She’s seeing more people approach her ready for treatment, but the lack of local detox services remains a problem.

“People want to detox and there’s no beds,” said Rai. “They want help right now, but there’s nowhere to go.”

Detox is considered the first clinical phase of a person’s recovery from substance addiction, a service that the Ministry of Health defines as “medical withdrawal management” for those who can check themselves into a facility. The closest detox facility to Port Alberni is in Nanaimo, an area that over the first six months of 2025 had a fatal overdose rate of 42.8, compared to Alberni’s 74.1.

“Island Health is planning to increase the capacity and accessibility of detox services in Nanaimo, which will improve access for people living in the Alberni Valley,” wrote the Ministry of Health in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “While Port Alberni does not currently have inpatient detox beds, individuals from the region can access detox services in Nanaimo and may be supported with recovery beds in Port Alberni following discharge.”

The province plans to add six “stabilization and supportive recovery beds” this winter to what is already available in Port Alberni, although detox might first be required for some seeking recovery from substance addiction.

“Stabilization and supportive recovery services provide structured environments for 30-90 days for people living with substance use who have completed or do not need detox,” stated the ministry.

The agony of withdrawal

The detox process is extremely painful, and can be difficult for loved ones to witness, says Rose Chester, who used fentanyl, heroin and cocaine for seven years. She’s been clean for over two years now, since she decided to leave the Downtown Eastside to return to her home Ditidaht First Nation community on Nitinaht Lake.

“All my friends on the streets were dying around me,” recalled Chester. “I didn’t really have anybody. A lot of things were going through my head. I was so suicidal and alone.”

But things didn’t get easier after she returned home, as the effects of withdrawal made her sick. She was at risk of having seizures, convulsions, heart attack or a stroke.

“Your body really, really aches,” said Chester of the withdrawal period. “It aches so much that you can’t get up and you can’t barely walk. You’re walking like you’re hunched over because you can’t stand up straight.”

She admits that this became an ordeal for her family to witness.

“They wanted me home, but they didn’t understand the withdrawals because they weren’t drug addicts,” she said. “They didn’t like what they were seeing. It was terrible, I was getting angry, I felt hurt and I felt alone. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t drink or do anything when I was on the street. Then when I came home, I was like that.”

Chester was initially taking methadone, a medicine used to treat heroin addiction, and connected with a doctor in Port Alberni for treatment. But with no medical attention available in Nitinaht, the regular hour-an-a-half drives on a logging road to Port Alberni became a struggle as Chester fought to get better.

“They set me up in Port Alberni to get the juice. I couldn’t do it, I just couldn’t get the ride every day,” she said, noting that her treatment improved with a change of medication. “They made an emergency trip to Nitinaht for me to try the suboxone. They sat there all day with me, they gave that to me every half hour.”

After a few months Chester was able to get a suboxone shot just once a month in Port Alberni, a treatment she continued for one year until she was ready to go off it.

“I slowly started to eat and I slowly started to want to take care of myself and get better,” reflected Chester, who since January has worked as an educational assistant at the Ditidaht Community School. “I feel really good. It took me a year to be in the right state of mind to do anything for myself.”

First Nations gap widens

While Chester reflects on the progress of her recovery, many others remain in the grip of substance addiction. While the provincial rate of fatal overdoses has declined this year by 25 per cent, Indigenous people continue to be disproportionately impacted by the crisis. The gap between Aboriginal people and the rest of the population has widened, as Indigenous people are 6.7 times more likely to die of a drug overdose than the rest of the B.C. population, reported the First Nations Health Authority in April.

It has now been a year since the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council declared a state of emergency for the overdose crisis, calling on provincial and federal governments for more support. A two-day summit on the crisis in May that involved Nuu-chah-nulth leaders and health providers found that tragedies are preventable by removing delays in the addictions treatment system. When someone is ready to detox, help must be available immediately, concluded the forum.

“All of our staff in our communities - which are really good - they’re just stretched to the limit,” said Cloy-e-iis, Judith Sayers, president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council. “They can’t take on the extra strategies that we’re trying to put in place.”

The NTC determined that nearly $800,000 is required over three years to better resource the needs of Nuu-chah-nulth communities, but provincial and federal officials have been reluctant to commit any additional funding.

“I think there’s recognition of our needs, but they’re in such a dire financial situation – or they tell us that,” said Sayers.

Currently the provincial government faces a $11.6-billion deficit in 2025, a shortfall that has increased over the past three years and is expected to grow in 2026. Government revenue has declined, due in part to Prime Minister Mark Carney dropping the carbon tax before the federal election last spring. As a government levy that drivers previously paid while fueling up, the loss of the carbon tax is expected to cut $2.8 billion from B.C.’s revenue this year alone.

“We presented our budget to implement a strategy to the health minister about a month ago. She just basically said she has no money,” said Sayers of a recent meeting with B.C. Health Minister Josie Osborne.

The Courtenay-Alberni member of parliament has also tried to get federal dollars for the Nuu-chah-nulth cause.

“Gord Johns met with the health minister for us, and she said she has absolutely no money,” noted Sayers.