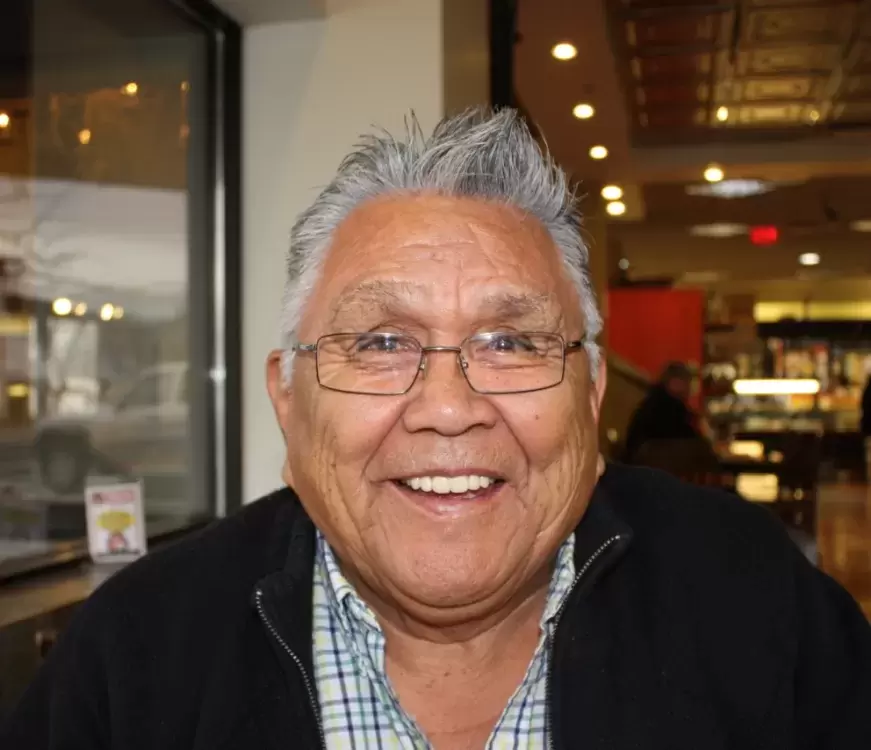

He was born and raised in his Tla-o-qui-aht homeland, but Tommy Curley’s stay in Seattle, Wash. during his younger days helped shape the popular music-loving disc jockey that he is today.

Thomas Curley was born Aug. 13, 1939 to Ernest and Cecelia Curley.

“I’m not sure but I might have been born at Kildonan… There was a cannery there at the time and lots of people were working there,” Tom shared.

“I grew up in Opitsaht but would spend my summers with my grandparents because our parents would be out fishing,” he remembered.

“Every summer my parents would bring us younger kids to Christie (residential school) to visit our older brothers.” The family would row from Opitsaht to Kakawis, just around the corner, but far enough to keep most kids from sneaking away from the residential school to Opitsaht.

One particular day, Tommy’s mother was carrying a sack along during one of those visits to Christie.

“I didn’t think anything of it…I thought maybe it was chumus (treats) for my brothers,” said Curley. Little did he know the sack contained his clothing and he found out too late that he wasn’t going home that day with his parents.

At the tender age of five, Tommy was playing up the hill with his older brothers when he realized he hadn’t seen his parents in a while. He looked down the hill to the beach where he saw his parents walking toward their canoe.

“I started screaming and ran down the hill calling for them,” he said. Curley said he waded into the water, chest-deep, franticly crying for his parents, whom he said, never looked back. In hindsight, he knew that it was probably too painful for them to look back at their young son.

“My brothers would tell me we’d be okay, they’d look after me, but the Brother, the supervisor, he laughed at me for crying,” Curley remembered.

The first night was the worst, he said. Young Tommy, under the cover of darkness, would go from bed to bed searching for his brothers Oliver, Nelson and Francis. He didn’t find them that night but he remembers hearing other kids crying in the darkness. It was probably their first night there also, he guessed.

Curley stayed in residential school for 10 years. The first three were the hardest because he stubbornly hung onto his language and couldn’t understand why he and the other children were being beaten for speaking it.

“I started to notice what we were being hit for, so I tried not to speak it around the nuns anymore,” said Curley.

In his late teens Curley joined his family on a trip to Mount Vernon, Wash. to pick strawberries.

“There was a couple of people that would recruit berry pickers up and down the coast,” said Curley.

At about age 16, Curley boarded the back of a pick-up truck with his family. There were about 15 people in the back of that pick-up truck bouncing over the new and very rough, windy dirt logging road that connected Tofino to Port Alberni.

“We were just covered in dust by the time we got there,” he laughed.

From Port Alberni the family boarded a train to Nanaimo, then took a ferry to Vancouver. In Vancouver the family climbed into the back of another pick-up truck and made their way to the berry field camp at Mount Vernon.

The camp was made up of little shacks that the families stayed in. One shack served as a store but still everyone had to go into town to buy the groceries.

“My late uncle Paul Sam and his wife Alice – my dad’s sister – were there, and we used to have to get up at 3 a.m. and board the buses,” said Curley. They would pick in the fields for hours, sometimes until sundown which would be about 11 p.m. in the summer.

“I never knew how much I made because everything went on my mom’s ticket; they used to punch a ticket for our strawberries,” he said. “We picked as a family and mom bought the groceries and it was a good thing because we always had food,” Curley continued.

And they always had plenty of strawberries. “I’m still crazy about strawberries even though that’s all we had to eat sometimes,” Curley laughed.

Life at the berry picking shacks was a little like camping in summer cabins. There were plenty of people from home occupying some of the nearby cabins. Some nights were so hot the Curleys and others would sleep outside under the stars.

It was after his final season picking strawberries that Curley became separated from his parents.

“They (the farm owners) were going to bus us to Seattle; all us young fellows from Opitsaht went on that bus and mom was there,” he recalled.

Once in Seattle the young men went to Pioneer Square, the place where, according to Curley, all kou-uss (aboriginal people), hung out. Tommy was there with his brother and a few others from home. They would go to the Britannia, a tavern near Pioneer Square, and listen to country music on the table-top juke box.

Curley began playing pool and by the time he looked up his brother had disappeared.

“I lost everyone, my brother Nelson…I didn’t see him again for months,” he said.

Tommy remembered walking for miles to all the police stations and hospitals he could reach but nobody had any record of his brother. He finally heard good news when he called a hospital and was told they had no Nelson Curley but had admitted a Ernest Curley.

“My brother was a junior. His real name was Ernest Nelson, but we all called him Nelson,” said Tommy.

Apparently, Nelson had been involved in a fight the night he went missing and wound up in jail. While in jail he tested positive for tuberculosis and was sent to a sanatorium.

As the summer wore on Tommy found himself alone and homeless in the big city. One night he went to a tavern where he met a young man from Mexico who invited him to stay at his home with his family and there he stayed for a while.

As the summer of ’61 was coming to an end, and with colder weather setting in, his search for a place to live became urgent. He spent about a month living in an empty chilly, concrete building on the Seattle waterfront with other homeless men.

“I didn’t know how to access social services and it was getting cold…I had no blankets and had to use cardboard,” he remembered.

One morning Tommy awoke to hear familiar-sounding voices. I looked out and saw a woman who looked kind of familiar and when she saw me she yelled, ‘hey, Tommy!’ It was fellow Tla-o-qui-ahts Marti (Martha) Charlie and Johnny Charlie and they happened to live nearby.

The Charlies took Tommy in and he worked as a laborer on the construction of the Space Needle.

“I did manual labor, only made enough to eat and I never got off of the ground. They never let us go up the Needle,” he said.

Then one day his parents showed up at the Charlie’s door.

“I’d never been so happy to see mom and dad,” Tommy remembered. “They came to get me. They were worried about me,” he said. Within days Tommy was heading back home to Canada.

Once back home Tommy started working in the fish plants that once dotted Tofino’s shoreline and he would sometimes go out fishing with his father. In later times he went logging.

In his free time he joined Walter Martin, Ray Williams and Howard Tom in a rock n roll band; they called themselves the Roving Ramblers. Curley was the lead singer and he said they performed all over the west coast.

Tommy remembered their first stint at a talent show in Ucluelet. As the curtains opened Walter Martin played a rousing riff on lead guitar.

“My knees were shaking, I was so nervous, but the crowd roared and I could see my parents sitting there so I just started singing my heart out,” he recalled. His mother was screaming and father sat there, smiling ear-to-ear. They were so proud of their son.

Eventually Curley met his first wife, Delores Charlie, after she was released from the TB hospital in Nanaimo. They had three children but the marriage didn’t last.

Little Tommy Jr. became sick with a raging fever when he was about a year old. He needed to be resuscitated at the hospital and, though his life was saved, he suffered profound brain damage. He required care for the rest of his life and passed away at the age of 26.

A daughter, Christina also passed away as a young woman.

Tom has a son, Marvin and some grandchildren.

“One of the best things that ever happened to me was meeting my wife, Christine in Tofino,” said Tommy. At the time Curley was drinking heavily and had suicidal thoughts. With the support of his wife, Christine and advice from a friend, Greg Jarvis, he was able to stick to a more positive life path.

And even though he’s been through some rough times, Curley says his life has been a great experience…all of it, because it’s made him the man he is today.