Three young members of Ahousaht First Nation are dealing with a rare bone disorder through a combination of cutting-edge medicine and traditional spiritual healing.

On May 6, parents Rob and Nellie Lindsay will be wearing yellow to mark Wishbone Day, an international awareness campaign for Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI), better known as “brittle bone disease.”

People with OI are unable to create healthy collagen, the all-purpose protein that connects tissues in the skin, bone, muscles and organs. OI can lead to bone deformities and those bones can fracture easily. The disease can lead to a host of related symptoms, affecting hearing, speech, eyesight and motor skills.

“People call it ‘brittle bone,’ but it’s more than that,” Nellie said. “In the 1800s, that’s all they knew about it, and they didn’t make much progress until the 1940s at the Shriner’s Hospital in Chicago.”

Nellie and Rob are now determined to educate the public about OI, which affects about one in every 12,000 people.

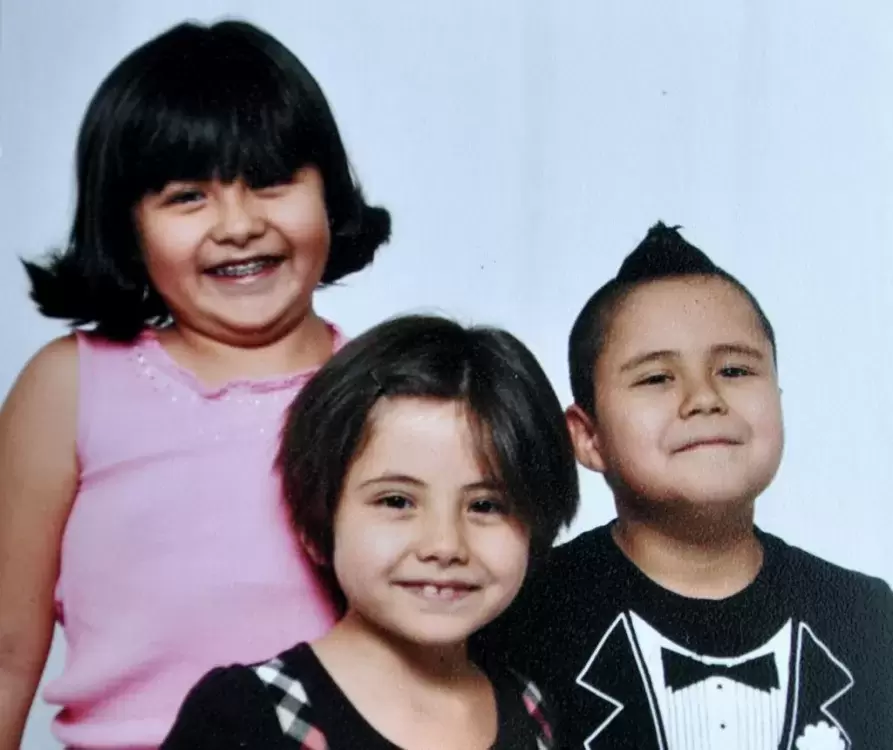

Their daughter Cedar, 10, and twins Eric and Sequoia, have been diagnosed with Type 3 OI, known as the “progressive deforming” type. Rob, who is non-aboriginal, has lived with Type 3 OI his whole life, and hopes to spare his children some of the hardships he has faced.

“I got it from my dad. There wasn’t much known about it when I was younger and I was brought up just trying to live the everyday normal life,” he said.

Before Cedar was born, doctors believed there was only a 50 per cent chance she could inherit OI, and that there might be a further genetic protection.

“My OB/gynecologist in Nanaimo said she believed, because I am aboriginal, that my offspring could not inherit the gene,” she said. “Now, we are the only First Nations family in B.C. with OI.”

Cedar was born with three bone fractures, to her right hip and elbow and to her collarbone. She was also born with an abnormally high pain threshold. As a baby, Cedar suffered numerous fractures but rarely cried. Rob said the high pain tolerance is a common symptom and it actually compounds the problem.

“I was brought up with the ‘Suck it up, Buttercup’ ethic. Had I been educated about this condition I would have been able to avoid some of the damage I’ve done to myself.”

After a career as a cook that has been punctuated by periods of injury and recovery, Rob said his condition has deteriorated to the point where he is no longer able to handle the physical work.

“I always tried to push through the pain when I was hurting. If I had listened to my body I would have found something less physically demanding. Now I need to set an example for my children.”

As a child, Rob was not allowed to play sports, but he did ride a bicycle. That is, until what would have been a routine spill and a few scrapes and bruises turned out to be a compound fracture of the leg. He and Nellie, albeit reluctantly, restrict the physical activity of all three children. While Sequoia is the least affected, she still bruises easily, and with that high pain threshold, does not telegraph when she is injured.

“It’s very difficult for them. And it’s very difficult for people to understand how they are affected,” Nellie said.

Even physicians can be uninformed about OI and fail to understand how fragile their children’s bones are. Nellie said a few ER doctors have tried to dismiss the family without taking X-rays when they bring one of the children in with a suspected fracture.

On the other end of the scale, one ER doctor called Child Protective Services when he saw Cedar’s medical chart with multiple bone fractures and chronic bruising. That required a call to Victoria and the issuing of a physician’s letter specifying that Cedar had Type 3 OI.

“We go in so often, we know which ones (physicians) are the best now,” Nellie said.

Cedar, Sequoia and Eric attend Wood Elementary. While the family has moved numerous times due to health-related fluctuations in Rob’s earning power, they have stayed at the same school. Wood staff have always provided a safe environment and their grandmother, Iris Sanders, just happens to be the native support worker.

On the dark side, however, the Lindsays have been warned that the Special Needs bus that their children have used will not be funded for the next school year.

Nellie said her extended family, including her grandparents, Tony and the late Evelyn Marshall, parents, Dave and Jeanette Jacobsen, have created a strong support system for the children, physical, financial and most importantly, spiritual.

“We do a lot of cleansing and prayers and ceremonies. Before Cedar had surgery (last Nov. 23), we had a potlatch, where we had songs and dance and brushing.

“We have a lot of spiritual support. That’s what keeps us going.”

The Lindsays have also been able to connect with other OI families through social media, to share their experience and provide mutual support.

“I’m really grateful to Facebook. I’m in contact with people in Australia and the United States, and all over the world,” Nellie said

Of the three children, Cedar is the most affected by the disease. The surgery last fall, at B.C. Children’s Hospital, was to correct the curvature of her spine, known as scoliosis. She has difficulty using tools like pencils, and needed a helper at school in Kindergarten and Grade 1.

Cedar has also undergone both physiotherapy and occupational therapy. Eric, who has boutonnieres – stiffened middle fingers – undergoes physio, occupational and speech therapy once a week, but thanks to intensive physio, should be able to avoid the need for scoliosis surgery like Cedar’s. All three also undergo daily therapy at home, between visits to the specialists.

The family travels regularly to B.C. Children’s. Every four months, Cedar and Eric have undergone intravenous treatment with pamidronate, to slow down or possibly reverse the scoliosis. Sequoia will begin the IV regimen in July.

“We’ve seen good results with the pamidronate,” Nellie said. “Less breaks, less severe and the recovery is faster.”

The children also undergo regular X-rays and bone density scans to monitor their development.

Another accompanying symptom of OI is a weakened immune system. A simple cold inevitably progresses to the flu and sometimes, to pneumonia. Intestinal bugs are another frequent companion.

“We had a really quiet winter, with no sickness,” Nellie said, then added that the children have experienced illnesses since the weather began to warm up.

Despite the limitations on their lives and the ongoing discomfort and medical treatments, Nellie said her children continue to be upbeat and cheerful. Their ongoing illness also makes them sensitive to other children in need, she added.

“When Cedar was six, one of her friends was undergoing treatment for cancer. At the time she had beautiful long black hair and she had it all cut off – 14 inches – to donate for a wig.”

Living with OI is a constant challenge, but Nellie said her children have already proven their determination to live life to the fullest.