The future of Indigenous rights in British Columbia will be different than how they were recognised in the past, according to legislation about to be put into law in Victoria.

On Thursday, Nov. 28 Bill 41 receives royal assent, making B.C. the first Canadian province to follow a call from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to enact the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Guided by the principles of UNDRIP, the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples act passed unanimously in B.C.’s Legislative Assembly on Tuesday, Nov. 26 after being introduced just over a month before.

The bill was developed by the provincial government in partnership with the First Nations Leadership Council, a body comprised of representation from the Union of BC Indian Chiefs, the BC Assembly of First Nations and the First Nations Summit.

Cheryl Casimer, the First Nations Summit’s political executive, said that all of the over 200 Aboriginal groups in B.C. had the chance to review the legislation before it was tabled in Victoria.

“Even though we’ve won numerous court cases in the province that upheld Aboriginal rights and title, it never really went far enough to be reflected in the laws,” she noted. “Now the provincial government is making that commitment to align provincial laws with the standards set out in the United Nations declaration.”

That alignment is expected to take several years, encompassing approximately 5,000 laws that need to be brought into compliance with UNDRIP. Priorities for implementations are child welfare reform, amendments to the province’s Environmental Assessment Act and forestry legislation that puts First Nations in more control over the management of their territory.

“The closures that are happening are affecting all of our communities - whether you’re Indigenous or non-Indigenous - it’s the livelihood of many families and we need to figure out ways how we can revive that industry,” said Casimer. “First Nations involvement has been limited in the past to addressing a referral, that’s never been acceptable. First Nations need to have a larger role to play.”

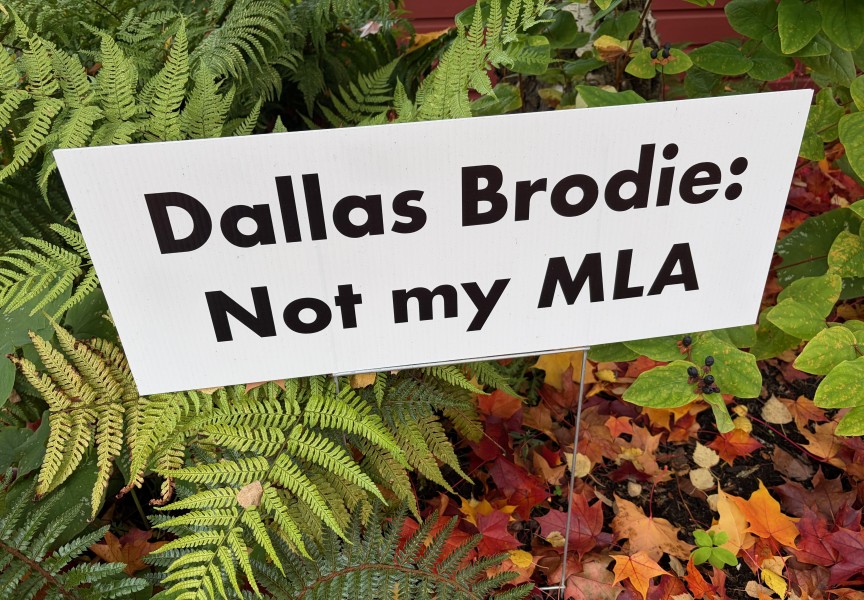

Although Bill 41 passed unanimously, it didn’t progress into law without a succession of questions from the Opposition Liberals. MLA Ellis Ross, a former elected chief of the Haisla Nation who currently represents the Skeena riding, cautioned about “political fanfare” with legislation’s introduction.

“Generations of Aboriginals have gone through life without hope,” he said, stressing the need of “individual band members getting their own future on their own terms.”

“Our people need opportunity, economic opportunity to be more precise,” he added while the bill was being discussed in the legislature.

While elected chief of the Haisla, Ross signed a $50 million deal with Kitimat LNG for a terminal to be built on the First Nation’s reserve land. As major natural resource projects are proposed in B.C., it’s yet to be determined how Bill 41 will empower First Nations who want to push forward their own developments – and what rights those who oppose large-scale initiatives will have.

The province retains authority to decide on major natural resource projects if it’s deemed to be in the public interest, while Bill 41 does not give any one First Nation the ability to veto a development, according to questioning while the legislation was being clarified. The words “free, prior and informed consent” were brought up by Liberal MLA Michael Lee during a committee discussion on Nov. 21.

“The usage of those five words in combination does not mean veto. Does the minister agree with that?” asked Lee of Scott Fraser, minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation.

“It does not mean veto”, responded Fraser, although he noted that the new law will ensure Indigenous peoples have a stronger influence on the government’s decision making process. “The time for government to say, ‘This is how we're going to do it; take it or leave it,’ is what we're moving away from.”

On Nov. 26 a joint statement was released by the government leaders and First Nations representatives who wrote Bill 41.

“It is time we recognize and safeguard Indigenous peoples’ human rights, so that we may finally more away from conflict, drawn-out court cases and uncertainty, and move forward with collaboration and respect,” reads the statement.

This is exactly what the Nuchatlaht wishes the province would do with respect to a title claim currently before the B.C. Supreme Court over the First Nation’s right to territory on northern Nootka Island. But now the provincial government has applied for the court to drop the case.

“The Crown lawyers of B.C. continue to make our case far more expensive than it should be, using every possible tactic of procedural delay,” wrote Tyee Ha’wilth Walter Michael to B.C. Attorney General David Eby. “This is not the honourable conduct of litigation.”

Looking forward at the work required to enact the UNDRIP principles, Casimer remain optimistic that the current NDP-Green government will continue to implement laws respecting Indigenous rights.

“I’m not too concerned about the existing government, who knows what happens in an election,” she said.