This fall a new nursing stream is coming to six universities in B.C., offering Indigenous graduate students training that aims to empower First Nations to determine their own path to wellness.

The Indigenous Graduate Education in Nursing presents an alternative to the well-established clinical approach to health care, a system that for many who live in remote communities is broken, according to input that helped the guide the new program. With the goal of training up to 24 graduate nursing students to work in Aboriginal communities, the stream is being introduced in September to the University of Victoria, Thompson Rivers University, Trinity Western, the University of Northern B.C. as well as the University of British Columbia’s Vancouver and Okanagan campuses. Plans have a minimum of two Indigenous students in the stream at each learning institution.

The program’s intention paper notes a “deficit” in health care reform for Indigenous people due to the existing “treatment focused model”.

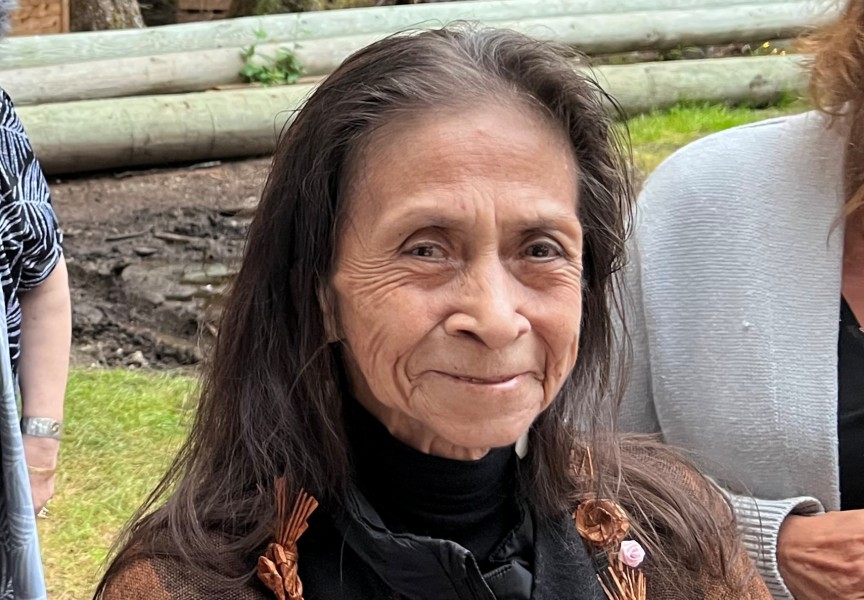

Lisa Bourque-Bearskin is an associate professor in UVic’s School of Nursing and the lead researcher behind the new educational stream.

“First Nations communities are being held responsible for delivering their own health care services, so they need that Indigenous nursing leadership there to support that transition,” she said. “We know Indigenous nurses are the primary contact, are the most trusted health care professionals within our communities, but if they’re not at the decision-making table to help us co-design these, we’ve missed the boat again.”

Part of the solution is getting more Aboriginal people to become nurses and return to their communities to lead health care reform, but institutional barriers have gotten in the way, said Bourque-Bearskin.

“We know right now that there’s significant barriers getting into graduate education programs, so we do not have the Indigenous nursing population at that level,” she said. “I think one the biggest barriers is the stats course.”

There are no accurate counts of how many Indigenous nurses are practicing in the province, as the B.C. College of Nurses and Midwives cannot require its members to declare their Aboriginal identity. But an attempt was made in 2016 by a study from the University of Saskatchewan, which identified 1,305 Indigenous professionals out of the 43,495 registered nurses it counted in B.C.

And even the First Nations Health Authority employs a disproportionately low number of Indigenous nurses. Out of the 150 who directly work for the organization to support First Nations communities, only 37 declared themselves to be Indigenous.

The lack of Aboriginal nurses who are available to serve their own communities can be partly attributed to a sense of health care elitism, said Joanna Fraser, a research associate at UVic and North Island College who helped develop the graduate Indigenous nursing stream.

“Elitism in that there is only one way of doing health care, which is very medical and Western,” she said. “What we’re talking about is very different approach.”

“I had a baby and toddler throughout nursing school, and I was working two or three shifts on weekends to support the commute down there,” said Dick. “It was a lot of work.”

“They were welcoming me and trusting me to provide this health care,” said Dick. “It is worth it when you get that reward in community feedback.”

For the young Tseshaht member, the career fulfills a role she had already found herself in with her family circle.

“My grandmothers were both nurses with the tribal council,” she said. “Also, I had the privilege to take care of my great grandfather at the end of his life, in the last decade when his health was declining. He was just a big part of my life and caring the Nuu-chah-nulth way of being really propelled me into the nursing program.”

But this is exactly what can be lacking in the health care that remote First Nations receive, according to input gathered for a presentation on “Nursing the Nuu-chah-nulth Way” given in April at UVic for advanced practitioners.

“So, you can have somebody with no training who is super loving and caring, and that has more healing properties than someone who can prescribe your medication but not look after you at all,” states a testimonial from an unidentified resident from the Hesquiaht community of Hot Springs Cove. “You are more than body; you are like heart and soul. That needs to be looked after just as much as your body does.”

Another anonymous respondent spoke of the Clayoquot Sound community’s isolation from any medical care.

“It’s costly to go in and out,” said the resident. “Most of the time I talk myself out of even going.”

The historical dilemma has been the inability of health care professionals to understand the needs of the First Nations communities they’re serving, said Jeannette Watts, the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s nursing manager.

“For an outsider coming in to understand that there are community protocols beyond those nursing standards that you’ve been educated in is really key,” added Fraser. “That’s why Indigenous nurses are key to leading this process.”

Bourque-Bearskin believes that First Nations need nurses who got into the profession not just for secure employment, but to help the communities they came from.