In effort to address ongoing critical gaps in our understanding of Indigenous health, EHN Canada hosted an online webinar on March 10 to highlight the disparities in healthcare access among Indigenous peoples living in urban centres.

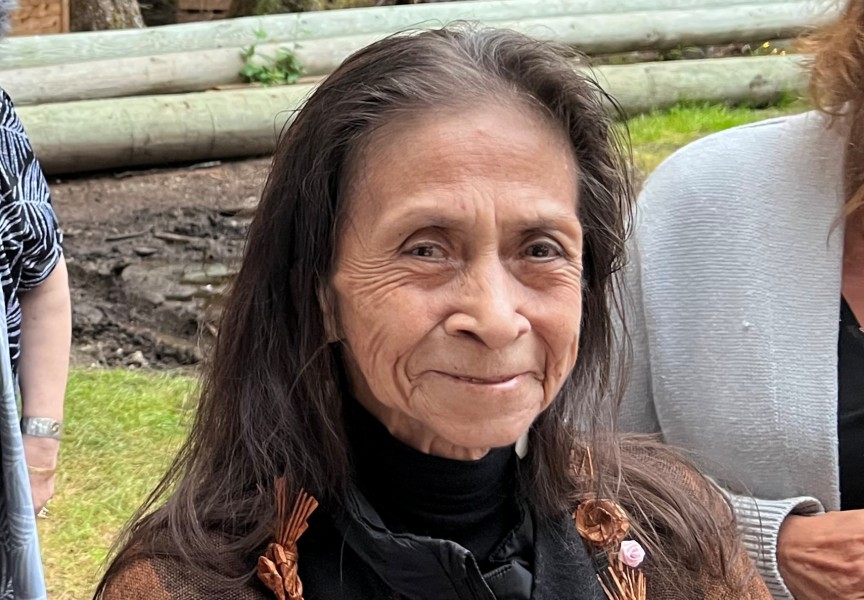

Hosted by Celina Sqwasulwut Williams, a spiritual advisor at Ravenswood Consulting, participants were guided through the current state of the healthcare system and how it needs to improve its diversity and inclusion measures for Indigenous communities.

Williams said she can speak to being marginalized within Canada’s healthcare system first-hand.

Raised within the Songhees Nation, Williams said she was in and out of police custody while growing up, had her driver’s license revoked 20 times, and was court mandated to Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous.

“I had a very tumultuous life,” she said. “I had doctors who didn't trust what I said. Nurses were tired of seeing me in and out of the hospital. Receptionists at doctors’ offices refused to book me because of so many missed appointments. And I had no medication because no one would prescribe anything to me.”

Her family ended up stepping in and brought her to a treatment centre, which Williams said opened her eyes to an array of services she didn’t previously have access to.

“I couldn’t advocate for myself,” she said. “When I arrived at treatment, I finally saw what I was missing out on my whole life – that my voice had never been heard before I stepped into the treatment centre. I was marginalized and I didn't even know it.”

Williams has been in recovery for nearly five years and aims to highlight the work that needs to be done so Indigenous peoples are no longer disproportionately impacted by Canada’s healthcare system.

“Canadian governance was built by non-Indigenous people for non-Indigenous people,” she said. “Our political leaders, at the time, created systems designed to oppress and exclude Indigenous people from opportunity to flourish.”

Those long-standing historical issues have led to ongoing consequences, she said.

Some of these consequences have been highlighted in a 2020 report published in the Canadian Journal of Public Health, which points to the “critical gaps” that remain in Canada’s understanding of Indigenous health.

“We have to give equal consideration to diverse, Indigenous and non-Indigenous world-views, such that one view does not dominate or undermine the contributions of others,” she said. “By using this two-eyed seeing approach, we can reshape the nature of the questions we ask in the realm of Indigenous health research.”

Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council Vice President Mariah Charleson said it’s been over 10 years since she sat on a working group during the first Truth and Reconciliation national event in Victoria.

Discrimination in Canada’s healthcare system is not a new conversation, she added.

In 2020, the In Plain Sight report identified “widespread systemic racism against Indigenous peoples” in B.C.’s health care system which resulted in a range of negative impacts, including death.

Led by independent reviewer Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, the report made 24 recommendations to address Indigenous-specific racism in B.C.’s health-care system.

Over a year after the recommendations were made, Turpel-Lafond said there have been “some” signs of progress but that they don’t go far enough.

Indigenous governments need to be co-creating law and policy with provincial and federal governments, she said in December.

Eliminating racism and the future of reconciliation depends on “our ability to make rightful space for Indigenous decision making and sovereignty,” Turpel-Lafond added.

“For non-Indigenous people who are working with Indigenous people, the best thing you can do is try to reach them at a human level,” said Williams. "Meet people where they’re at.”

Persisting conversations about discriminatory issues is the only way forward, said Charleson.

“It has to be the starting point for finding ways to provide culturally safe and accessible health care for all of our people, whether they live in urban centres, or in our rural and remote communities,” she said.

It wasn’t long ago that Charleson said her Nuu-chah-nulth “aunties and uncles experienced horrendous things in the Indian hospitals and within the Indian residential school system.”

“They were essentially treated as test dummies,” she said.

Those experiences have resulted in intergenerational post-traumatic stress disorders that can only be addressed if “our people feel safe when they're going to access basic health care needs,” Charleson said.

“Before we can even begin to right the wrongs that have been done, we have to highlight the truth,” she said. “We have to listen to the people who have experienced these things. We have to uplift their stories so that people know these events happened.”