This summer the Ditidaht are making another step in self determination, as the First Nation takes authority over the education path that will guide its community school.

Through an agreement made with the federal government, the southern Nuu-chah-nulth nation officially takes jurisdiction over its education services July 1. This transfer was done in partnership with the First Nations Education Authority, a body independent of government that formed a year ago to help Indigenous communities gain control over schools on their lands. The Ditidaht are the first Nuu-chah-nulth nation to partner with the FNEA to gain educational jurisdiction.

Funding for the Ditidaht Community School, which serves approximately 50 students in kindergarten to Grade 12, will still come from the federal government. But this jurisdictional shift will improve the financial support the school receives, according to Chief Councillor Brian Tate.

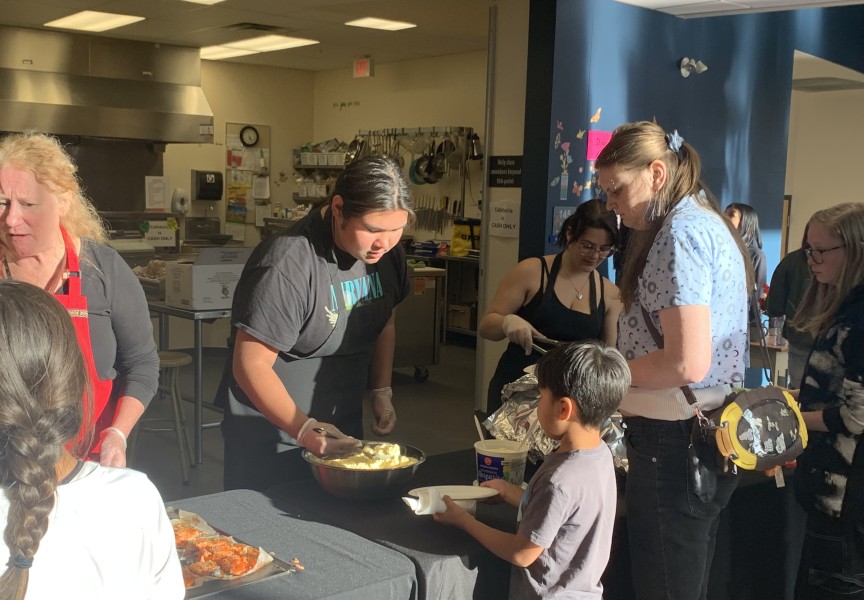

“The funding for Ditidaht Community School will be the same – if not greater – than school districts throughout the province,” he said during a celebratory event on June 29 in the First Nation’s village at Nitinaht Lake.

According to the B.C. Ministry of Education, federally funded on-reserve schools are operated by the local First Nations. But officially taking jurisdiction over its school will give the Ditidaht the final say over education as it works with the FNEA. The Ditidaht can now determine teacher certification, curriculum and graduation requirements.

“They have the ability to create a curriculum with culture and language at the forefront, with courses that relate to Ditidaht initiatives – blue collar, white-collar, legal, office administrators, managers – that’s what these goals are for, so that we all have a helping hand in our way of life in this village and our outside membership to come home,” said Tate. “Graduates grounded in Ditidaht culture and language, the ability of grads to go anywhere they want in college or university without penalty, that’s what will happen with this jurisdiction.”

A five-person board of Ditidaht members has been named to guide the direction of its school, and with jurisdiction any laws pertaining to education must have the support of 10 people from the First Nation.

Stephanie Atleo is president of the First Nations Education Authority and a member of the Cowichan Tribes, which gained educational jurisdiction a year ago.

“Jurisdiction is about taking control of your education,” she said. “Only you know what is right for your community, and that’s the power that you’ve taken back from the government, is asserting yourselves in the education your students and your community has.”

The Ditidaht’s village is accessed via a 70-kilometre gravel road running south of Port Alberni, or by a logging road running east to Lake Cowichan - routes affected by blinding dust in the summer and flooding in the winter. Like many remote First Nations, recruiting and retaining teachers is a foremost challenge for the school, but part of the aim of claiming jurisdiction is to gain more flexibility over how educators can be certified. Now existing teaching assistants can be certified as a teacher at the Ditidaht school, said Tate.

“It’s really made a difference in my community to bring the teachers and the principals to the table to talk about teacher certification,” said Atleo.

Requirements for a Grade 12 Dogwood Diploma will remain the same for the school, with minimum credits needed in phys ed, math, science, language arts and social studies. To earn a Dogwood students also need to take a math and literacy assessment in Grade 10, followed by another literacy assessment in Grade 12.

During the celebration Robert Joseph, a former elected chief and longtime treaty negotiator for the nation, reflected on how in the early 1970s nearly all of Canada’s First Nation students didn’t finish high school, a time when on-reserve unemployment across the country was 50-90 per cent. Over the years this has improved enormously, but a gap still remains. In B.C. 88.8 per cent of students finished high school within six years, while the completion rate for Indigenous learners was 69.4 per cent, according to the most recent statistics provided by the Ministry of Education.

“That’s what we’re up against,” said Joseph of the historic gap in high school graduation.

Negotiations for education jurisdiction began in 2007, but the Ditidaht would have gained it years ago if the federal government didn’t get stuck on using the First Nation’s business revenue to fund the school, explained Joseph.

“The confusing part for me is that education costs money, it doesn’t generate money, but they wanted us to pay for it through our own source revenue,” he said. “They wasted a whole bunch of time, there was no way we were going to sign anything like that.”

Former elected chief Jack Thompson was involved in education jurisdiction negotiations from the beginning. For him, the value of education became apparent as a child when his father worked as a logger.

“We’d be sitting around the dinner table, and my father would get home from logging, all wet. He said, ‘Don’t be like me, look at me’,” recalled Thompson. “We can get to the next phase now. We’ve got to build our own personal system that uses the resources that are around us.”