The Nuchatlaht are celebrating a victory amid a recent court decision recognizing Aboriginal title over a portion of its traditional territory, although it appears the small First Nation’s legal fight to gain authority over the whole claim area is far from over.

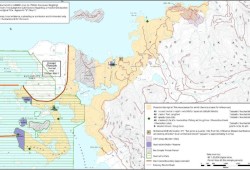

On April 17 Justice Elliott Myers released a judgement on the matter, which concerns the Nuchatlaht’s title claim to 201 square kilometres covering the northern part of Nootka Island. Myers determined that the First Nation has proved Aboriginal title over a portion of this area, land that mostly entails a coastal strip along the northwestern edge of Nootka Island. This section mainly doesn’t extend more than a kilometre inland, generally aligning with the provincial government’s argument to the court over what portions have been proven to rightly belong to the Nuchatlaht.

“In my view, with some minor exceptions, the province’s map delineates areas with respect to which the Nuchatlaht have met the criteria for Aboriginal title,” wrote Myers in his most recent judgement.

The judge also included some other sections, such as small islands in Owossitsa Lake and areas at the mouths of rivers by the historic sites of Opemit and Nuchatl. The recognized title sections lie in areas of less than 100 metres of elevation, as throughout the trial Myers has been unconvinced that evidence was presented of occupation far inland.

“Confining the boundary to the 100-metre contour reflects the distinction between the coastal and interior areas,” wrote Myers.

The judge referenced his previous decision from May 2023, in which he found insufficient proof that the Nuchatlaht regularly used Nootka Island’s inland regions.

“With respect to the interior, there is almost no evidence of use by the Nuchatlaht,” wrote the judge, citing research by Philip Drucker, who extensively studied northern Nuu-chah-nulth tribes in the 1930s. “Further, Dr. Drucker said that the Nuu-chah-nulth treated the interior and coastal areas differently in terms of ownership and had far less knowledge of the interior.”

As the parties went before Myers from March 11 to 15, part of the Nuchatlaht legal team’s argument was that entire watersheds should be recognized due to the First Nation’s traditional use of these whole areas.

“If they had a village site, they must have been using the land upstream to support their culture,” argued lawyer Jack Woodward in March.

The legal team even cited the Labrador boundary case from 1927. In this decision the Privy Council in London rejected Canada’s assertion that Labrador - which was not yet part of Canada at the time - should be limited to the coastal region. Instead, the Labrador boundary was extended far westward to the height of land, as it remains today.

But Myers remained unconvinced.

“A fundamental conclusion I reached was that the Nuchatlaht had not demonstrated sufficient occupation over the total claim area, and particularly the interior, to ground a claim for Aboriginal title,” wrote the judge. “Framing the claim as one over a series of watersheds (which encompass vast areas of the interior) does not change this analysis.”

The April 17 decision is the latest development in a case that began in early 2017 when the Nuchatlaht first filed their claim to the B.C. Supreme Court. The case has entailed a 54-day trial in 2022, leading to Myers’ decision the following year in which he recognized Aboriginal title over a portion of the claim area, but not all of it. Parties were given the opportunity to return to court for a week last March to determine the extent of title over limited areas in the claim.

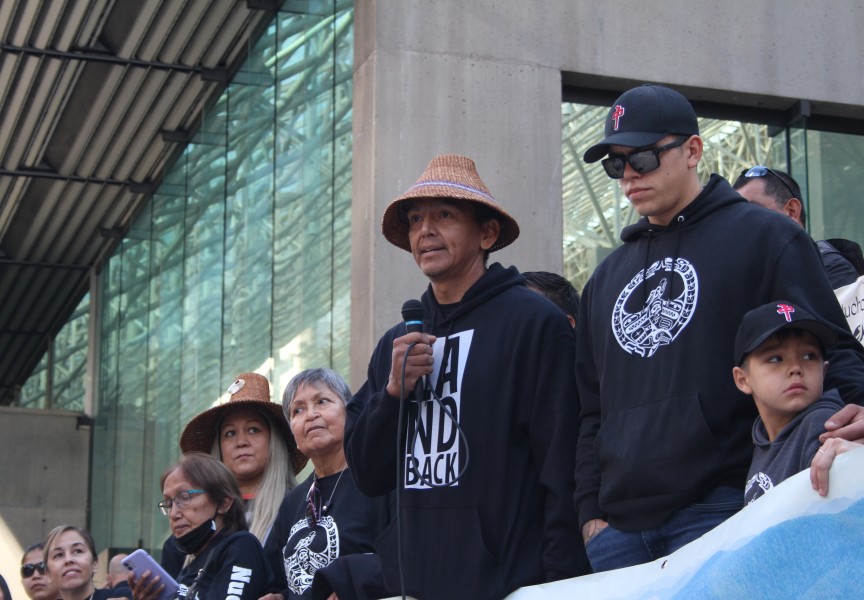

Although it has been a hard sell, the Nuchatlaht are calling the most recent decision a victory, marking the first time the B.C. Supreme Court has awarded Aboriginal title to a First Nation.

“We are celebrating this victory and looking ahead for the future of our nation,” stated Tyee Ha’wilth Jordan Michael in a press release from the First Nation. “There is still much that needs to be done to restore our land and heal our people.”

“This is a victory for Nuchatlaht, but we know that our territory didn’t stop at the bottom of the hill,” said Nuchatlaht Councillor Mellissa Jack in the release. “Our people used everything from the beaches to the mountain tops.”

Myers’ recent decision leaves the majority of the claim area as Crown land under B.C.’s Forestry Act. Currently Western Forest Products holds tenure of this area, although logging has ceased in recent years as the title case has been fought in court.

From the beginning a concern expressed by the First Nation, which has under 160 members, has been the extent of clearcutting old growth forests in their territory. The Nuchatlaht are now considering appealing the recent decision in an effort to gain title over the rest of their traditional territory.

“There has been industrial clearcut logging,” added Chief Michael. “There’s no thought about tomorrow. It’s take everything now. We want to do things differently.”

“We’re not just fighting for Nuchatlaht,” noted Councillor Archie Little, who stressed the importance of restoring wild salmon habitat. “We want to show the world that we can manage better, we can enhance better, and there will be enough for everybody.”

With some of their territory now recognized by the court, Nuchatlaht Councillor Erick Michael called the recent decision “a huge win for self-determination.”

“This is a real chance at becoming self-sustaining,” he said. “For far too long we’ve been isolated on this tiny little reserve watching all our resources getting stripped away, while not taking any real part in the economic development of our nation.”

“When all other avenues like the B.C. treaty process and reconciliation agreements did not work,

the Nuchatlaht were forced to go to court to prove their title,” stated Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council President Judith Sayers. [W]e are happy they have had some success and wish them continued success as they appeal to have the remainder of their territory declared Nuchatlaht title lands.”