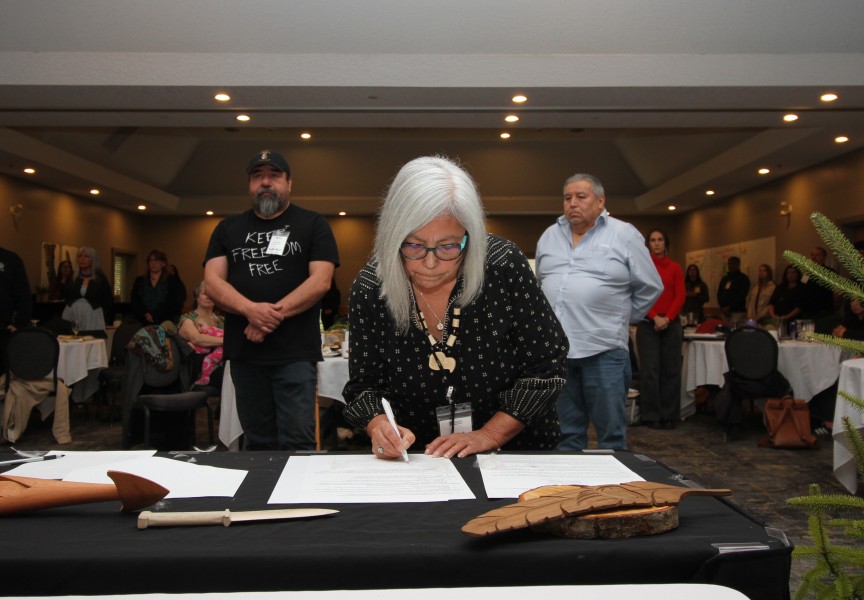

Sipping endless coffee under the dim lights of Port Alberni’s Barclay Hotel banquet room, Indigenous and non-Indigenous forestry professionals sat together for two days soaking in the first annual Indigenous Forestry Conference, Sept. 10-11.

They talked about closing the economic gap, innovative ways to increase market space, streamlining processes and fixing the stumpage system, the multigenerational aspect of forestry as well as creating a collective vision for the future.

Over the past two decades, B.C.’s forestry sector has been rocked by a litany of factors. These range from unsustainable harvesting practices depleting land resources, the decline in demand of paper due to digitization and the ongoing Canada-U.S. softwood lumber dispute to historically devasting wildfires and the mountain pine beetle infestation, according to a 2024 report by three unions (Unifor, United Steelworkers, Public and Private Workers of Canada).

The nosedive in production has sent a ripple of layoffs and sawmill closures across the province; Western Forest Products permanently closed their last Port Alberni sawmill in 2023.

“What are we going to do?” Emchayilk (Robert Dennis Sr.) asked the room full of forestry workers.

“Coming together here is the beginning. The challenge is going to be staying together to do something. And an even bigger task is going to be working together to solve it,” continued Emchayilk, a former Huu-ay-aht First Nations chief councillor and the current project chairperson of Iskum Investments. “Can we? Damn rights we can. If we go full gear, do the best we can, the hardest we can.”

Tseshaht Chief Councillor Wahmeesh (Ken Watts) acknowledged the diversity of the roughly 200 participants that attended the Indigenous-led event.

“When people talk about reconciliation, it’s not always about money or about land, it’s about standing up for what’s right as well,” said Wahmeesh. “From this hotel last year on Sept. 30, about 1,500 people walked with us to the former site of the residential school. Over half of those people were non-Indigenous people. Simply walking with us is a true act of reconciliation.”

Conference lead Trevor Cootes said the event was an “amazing success” that brought industry and First Nations together to have conversations and work as a collective.

“Next year, we will have more of a focus,” Cootes notes.

The future of forestry

Resource stewardship from an Indigenous perspective took centre stage during the second day of the conference, with Indigenous forestry consultant Marina Rayner leading the discussion.

“We need to take serious consideration about what needs to be harvested,” she said.

Rayner introduced the concept of cedar Sayassim Gardens, which translates to “in the future”. The model catalogues cedars that are accessible to Huu-ay-aht citizens.

“It’s managed for Huu-ay-aht traditional use,” she said. “We use cedar throughout every stage of its life. (The Sayassim Gardens) are located along main lines. They are located close to the community, they are located within a really important sacred site for the Huu-ay-aht. You can bring your elders out to the forest and be able to interact in these Sayassim Gardens in a whole different way for the next 300 years.”

Mike Green, a forestry manager with ‘Namgis First Nation, spoke about generational mistakes that impacted the Nimpkish watershed.

“What would you do if you were starting today?” he asked. “Need is not a number. It’s that total package of what you are doing.”

Chief forester for Western Forest Products Stuart Glen stressed the importance of outcome when it came to achieving government approval for Forest landscape plans (FLPs). He said a recent successful plan was tackled with “open-mindedness” and built “organically” from the bottom.

“How do you write a plan that respects connectedness? It’s not easy because just think of all those different relationships and how do you write in that context? We never actually wrote the plan until the very end, until we knew what our outcome is,” said Glen.

Gerald Cordeiro, forest development manager for Kootenay-based Kalesnikoff Lumber Co., spoke about the potential of mass timber, an engineered wood known as cross-laminated lumber.

“There is increasing market space (for mass timber) in the market for sure,” said Cordeiro.

“As the Indigenous control of tenure and the decision-making ability in B.C. expands greatly over the next few years, figure out what you are going to do a little differently than the people that came before did,” Cordeiro concludes.

Anyone interested in learning more about the Indigenous Forestry Conference is encouraged to visit: https://www.linkedin.com/showcase/indigenous-forestry-conference-ifc/