Is British Columbia on the right track in its handling of the opioid crisis? Or has the province’s approach to the eight-year-old public health emergency become a “failed experiment” in harm reduction and decriminalization measures, as argued by the upstart Conservative Party of BC?

With the provincial election approaching on Oct. 19, it’s hard to imagine a more pressing issue facing Nuu-chah-nulth communities. One month before that scheduled vote, the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council raised the urgency of getting more help from various branches of government with the declaration of a state of emergency for the interconnected toxic drug and mental crisis that continues to devastate families.

“This is a real emergency. We are losing too many, especially young people, to this crisis,” said NTC President Judith Sayers. “When we invest in mental health, education, housing and economic development, we can create a future where fewer people turn to opioids to cope with trauma and pain.”

The incumbent NDP, Conservatives and Greens have all addressed the issue in their campaigning over the previous months, although with diverse messaging and in different degrees of prominence on their respective election platforms.

Since the toxic drug crisis prompted the province to declare a public health emergency in April 2016, over 14,000 have died by overdose from illicit substances. Currently an average of six people are dying from toxic drugs each day in B.C., making it the most common cause for death among those under 60 – more than car crashes, homicide, suicide and natural diseases combined.

Fentanyl continues to be a major element of the crisis, as the lethal painkiller was found in almost 90 per cent of the deaths reported this year.

Although First Nations people comprise just four per cent of B.C.’s population, they account for almost 20 per cent of overdose deaths. Indigenous people face a fatality rate six times that of the rest of B.C., according to the First Nations Health Authority.

After some progress three years into the public health emergency, the rate of deaths climbed dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic and its corresponding societal disruptions. As the public was urged to socially distance to prevent infection, concerns grew that a growing number of illicit drug users were overdosing in isolation.

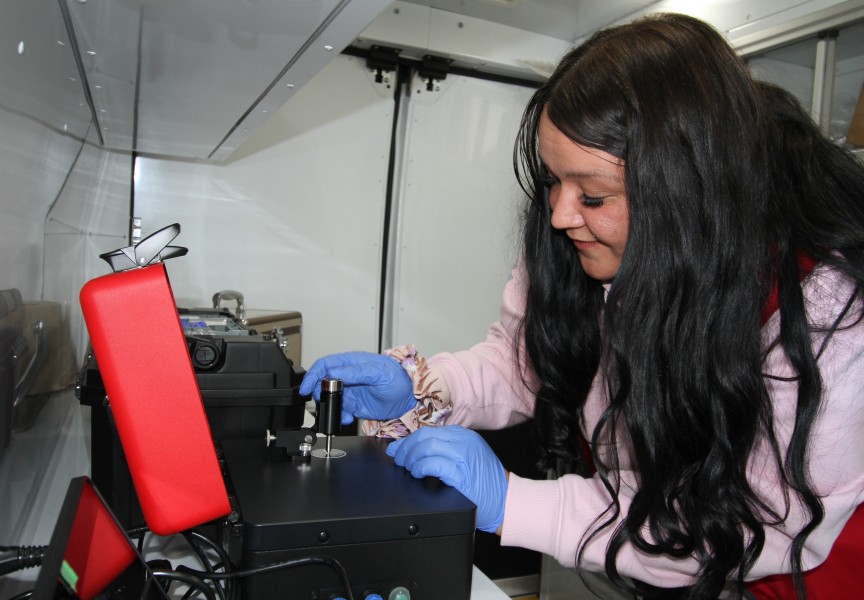

Harm reduction has emerged as a major facet of the province’s efforts to lessen the rising tide of fatalities. This approach entails various measures to decrease the danger that illicit drug users face, notably the use of supervised consumption sites, which have grown to number over 350 across B.C.

Just one overdose death has been reported at B.C.’s regulated supervised sites, but allowing drug use at these facilities and in their vicinity has created “a drug consumption free for all,” according to the Conservative Party of BC, which says that these locations will be shut down if they don’t “abide by strict standards of conduct.”

“We refuse to accept addiction as a lifestyle choice,” stated Conservative Leader John Rustad in a statement from the party. “Addiction destroys lives, families and communities. We will focus on prevention – ensuring that British Columbians, especially our youth, are equipped with the knowledge and support they need to avoid falling into addiction in the first place.”

Part of the reason supervised consumption sites have opened is to bring illicit drug users out of the shadows, into a public realm where recovery support is available if they are willing. In another major measure to reduce the stigma drug users face, B.C. became the only province to be granted an exemption from Health Canada under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Enacted for three years starting at the end of January 2023, this exemption frees people from criminal charges if found to possess up to 2.5 grams of the most common street drugs, including Fentanyl.

The province has also worked to prescribe safer medical alternatives like Hydromorphone to drug users, an effort that reached an average of 4,777 people each month last year. But a report from Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry in July noted that so far the health care system has shown a “limited capacity” to reach enough people with these safer alternatives, as the supply of street drugs is accessed by an estimated 165,000-225,000 people annually.

“The NDP’s failed experiments with decriminalization and ‘safe supply’ have cost us thousands of lives and torn communities apart,” argued Rustad. “The Conservative Party of BC will end this crisis, save lives, and get British Columbians back on track.”

On the other side of the political spectrum lies Sonia Furstenau, leader of the BC Greens. She spoke about the effects of the opioid crisis on Aug. 30, addressing a crowd in Port Alberni on the eve of International Overdose Awareness Day. During her talk the Green leader shared a story of a young man lost to drug overdose whom she knew while she was a teacher, and the Conservatives inability to understand the personal complications of the crisis. She feels that Rustad is weaponizing the issue for political gain, while supervised consumption sites should be a safe oasis for drug users.

“We need to lean into our best angels right now,” said Furstenau during the talk.

During the campaign the Greens have said that the government isn’t doing enough, and want monthly updates on the number of people accessing medical alternatives to illicit drugs. They accuse the NDP of not addressing the crisis “with the urgency and depth it demands.”

Long before the election, it appears that the NDP government recognized that widespread decriminalization could be a pollical risk. In May decriminalization was scaled back with a policy change that again makes it illegal to use in public spaces or hospitals. At the time Premier David Eby said that street disorder wouldn’t be tolerated as the government deals with the opioid crisis.

During the campaign period the issue isn’t at the top of the NDP’s platform messaging. Further down in the platform the party does note plans for a new treatment centre for construction workers, who constitute one in five of overdose fatalities. The party also mentions the opening of new Indigenous treatment facilities, such as the 20-bed Tsa̲kwa̲’luta̲n Healing Centre set to open on Quadra Island this fall.

Then there are plans listed that the NDP actually shares with the Conservatives, although either party is reluctant to acknowledge this. These include more training for school staff about the dangers of illicit drugs and an expansion to involuntary mental illness and addiction treatment that could be offered in correctional institutions and other facilities.

"We're going to respond to people struggling like any family member would," said Eby. "We are taking action to get them the care they need to keep them safe, and in doing so, keep our communities safe, too."

As the parties have disputed how the drug crisis should be handled, the number of people dying by overdose has actually declined this year. The most recent data from the BC Coroners Service shows 192 illicit drug deaths in July, a 15 per cent drop from the same month in 2023. Each of the first seven months in 2024 show a decline in overdose fatalities from the same periods last year, suggesting that – however devasting the crisis continues to be on families and communities – some of the methods put forth by the NDP government could finally be working.