Nearly three and a half months after roughly 7,500 litres of diesel oil seeped into the marine environment near Tahsis on the west coast of Vancouver Island, closures for shellfish harvesting are still in place.

The Nuchatlaht First Nation’s council has advised people not to eat any shellfish from local waters after a recent testing of Pacific oysters indicated the presence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Cancer-causing PAHs are formed during the incomplete burning of materials like coal, oil, gas, wood and charbroiled meat.

“I want to protect First Nations health around here,” said Roger Dunlop, a biologist and Nuchatlaht’s Lands and Natural Resources manager.

“The oysters had the highest levels of PAHs. They were well beyond what people should consume. Other jurisdictions around the world regard anything that’s 10 to the minus six, so anything greater than a part per billion is not safe for humans, and especially for infants. We’ve got levels way over that everywhere,” he said.

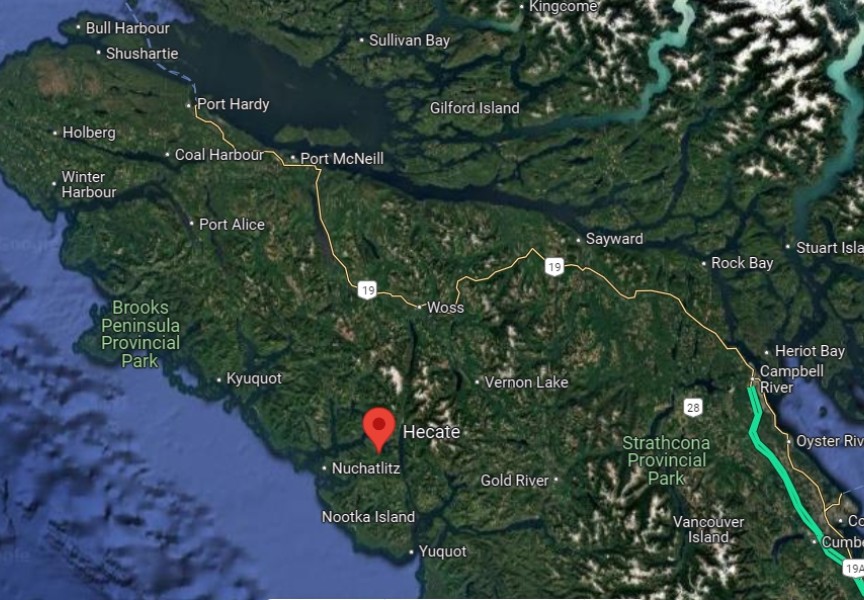

Dunlop is part of the environmental committee and the Unified Command that is working on the Lutes Creek diesel spill, which occurred Dec. 14, 2024 at Grieg Seafood’s site in Esperanza, B.C. in the heart of Nootka Sound.

The fish farm company spilled between 7,000 to 8,000 litres of diesel into the ocean due to human error during a fuel transfer operation on a floating concrete platform.

Two days after the spill was reported, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) invoked emergency chemical closures for all bivalve shellfish in Esperanza Inlet, based on recommendations from Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program partners.

After further analysis on Dec. 20, DFO expanded the emergency chemical closure area to include waters of Zeballos Inlet and Hecate Channel (Subarea 25-9) and the inside waters and intertidal area of Esperanza Inlet (Subarea 25-13).

The chemical closures remain in place and DFO says they “can revoke the closure when a recommendation is received, based on testing from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.”

About 45 days after the spill, tissue samples were collected from Rockweed, Pacific oysters, Manila clams and Bay mussels at 17 sites within the impacted area of the diesel spill.

“The clams are buried in the ground, so they weren’t exposed directly to the diesel fuel. Oysters were if the slick crossed them with the tide. Bay mussels are way in the high tide so they would have been only touched or exposed at the highest tide if there was diesel there,” said Dunlop.

He thinks DFO should also close the small inlets on the map that are hatched in green, but DFO said in an email that “they were not recommended for closure”.

“I personally saw on Dec. 23 diesel at the top of Espinosa Inlet opposite Chum Creek. The reference sample was dirty too,” Dunlop told the Ha-Shilth-Sa.

To mitigate the effects of the spill, Grieg Seafood said field crews deployed sorbent and containment booms at identified priority areas and surveyed marine mammals.

“No marine mammals were observed near the spill site, and all animals recorded appeared healthy, with no signs of distress,” the Norwegian-owned fish farm company said.

Grieg said crews, which included SCAT experts (Shoreline Cleanup and Assessment Techniques) from Canadian Coast Guard, also conducted shoreline assessments and drone surveys to determine the extent and potential impacts of the spread of the fuel.

Grieg went on to say that the Unified Command committee, which contains representatives from Ehattesaht, Nuchatlaht and Mowachaht/Muchalaht who have had their territory impacted by the spill, is now in the testing phase to determine the scale and range of the impact on the environment and shellfish area.

“All parties are focused on reopening the shellfish grounds as soon as it can be determined that the shellfish are safe to eat. Grieg Seafood has agreed to complete additional testing above what is required by the province and federal Governments, to assure further confidence in results,” the fish farm company said in an email, noting that another round of samples was collected at end of February and they’ll do another round at the end of April.

“It could take a year or a couple years before some of the sites are safe to eat again,” said Dunlop.

“There is an economic impact that surrounds this too. We don’t want to be closing the fishery for people if it could be open and safe. We don’t want to erase opportunities unless it’s the overriding health,” he continued.

Some clam diggers can earn up to $400 in one night, according to Dunlop, who used to run a clam management board.

Grieg Seafood acknowledged that the closure of the shellfish fishery has had “both financial and cultural ramifications for the First Nations impacted”.

The fish farm company said compensation discussions with Ehattesaht, Nuchatlaht and Mowachaht/Muchalaht are due to start once the full impact of the spill is understood.

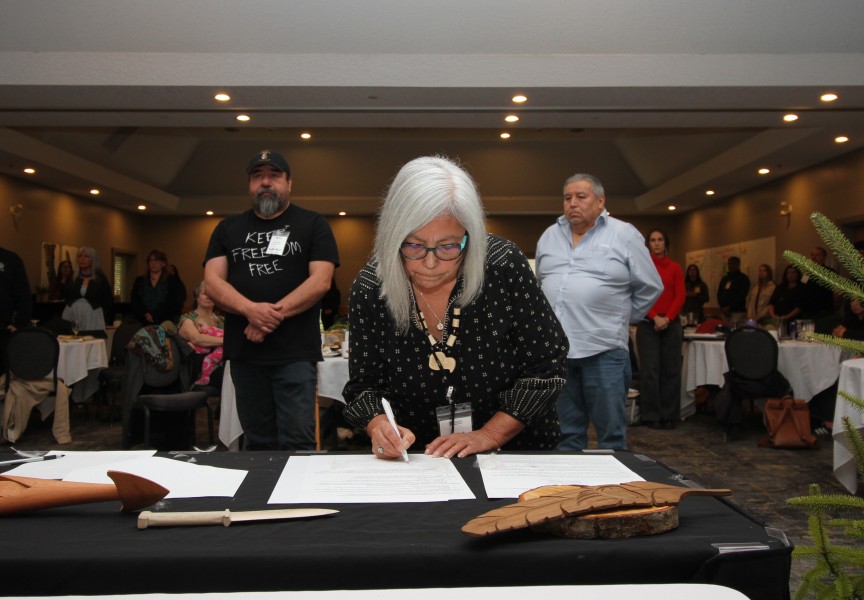

The Coalition of First Nations for Finfish Stewardship lists 17 Indigenous communities in B.C. that have formal agreements in place with fish farming companies. The Ehattesaht First Nation are among these, while the Nuchatlaht and Mowachaht/Muchalaht are not.

Dunlop wants to see federal regulations established that require fish farms to set-up fuel catchment systems at fuel storage facilities. Another big lesson learned from this spill, says Dunlop, is First Nations should have a sampling plan with their harvest sites pinned on a map.