Ahmber Barbosa’s interest in health care began at the age of four.

“I was in the delivery room when my brother was born,” she said. “It was just the most magical experience. I knew I wanted to deliver babies when I was that young, but there’s a few different paths you can take to do that.”

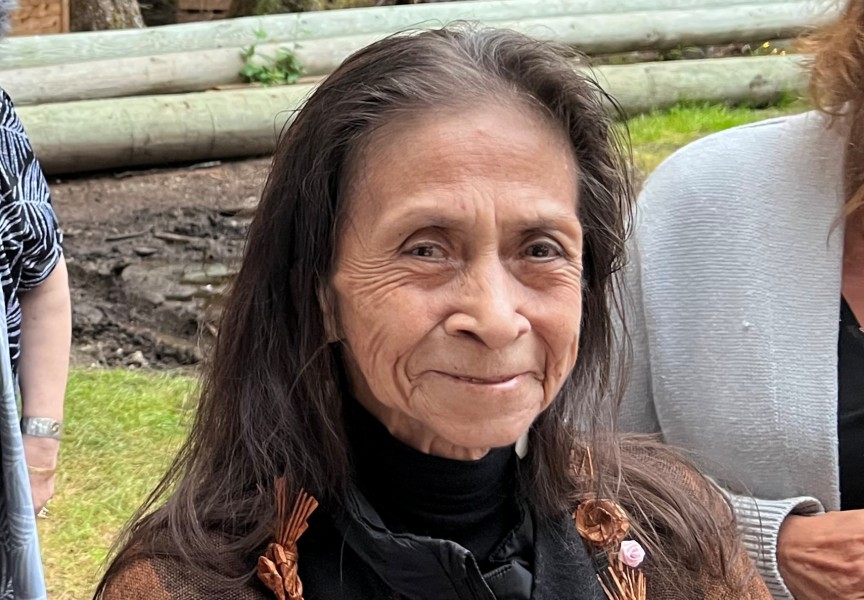

Now 29, the Tla-o-qui-aht member considered midwifery and nursing, following a family tradition of working in health care – including having a grandmother who was a long-serving registered nurse and a father who worked as a licenced practical nurse for 18 years. After earning an undergraduate degree in molecular biology at Vancouver Island University, Barbosa set her sights on becoming a family doctor.

“Family medicine gives a lot of flexibility in terms of where you can go,” she said.

She now awaits her third year of medical school, which begins June 9 in Duncan. She’ll experience a series of clinical placements in obstetrics (pregnancy, childbirth and the post-partum period), surgery, pediatrics, family medicine and even some psychiatry.

“We get to rotate through a whole bunch of different specialties so that when it comes time to pick our residency we have an idea of what we like,” said Barbosa.

So far, her favourite part of med school has been assisting general practitioners by interviewing their patients to prepare for when the doctor sees them.

“I love speaking with patients and getting to know them,” said Barbosa, who plans to eventually return home to Port Alberni to serve as a family doctor. “I’d like to focus on obstetrics and women’s health as well as palliative care.”

Like Barbosa, Savannah Sam also had to spend years away from her home community to earn her credentials as a medical professional. After becoming a registered nurse in 2019, Sam worked at the Nanaimo Regional General Hospital for three years – the busiest medical facility on Vancouver Island.

But she now works in Ahousaht, the place where she was raised, serving as the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s community health and home care nurse.

“My role is mainly immunizations,” said Sam. “Being able to interact with all the babies that come into the community, being one of first ones that sees them and provides them with some care that’s needed in their first days…I provide that care when needed.”

Since Sam was 10 she’s wanted to work as a nurse in Ahousaht to serve her people.

“I remember telling my grandma that I wanted to be a nurse,” Sam said. “She asked if I was going to work at home here.”

Being away from Ahousaht for nine years was hard, as she earned a formal education and gained experience in the field. But coming back as a medical professional wasn’t easy either, due to her deep familial relations in Ahousaht. It took a lot of convincing to gain the trust of some in her community.

“I’m related to a lot of people here as well, so I have to ensure that I will stick to my confidentiality piece, and that I have a licence that I have to look after,” she admitted. “They trust me now and it’s gotten a lot easier.”

There’s a lot to overcome for the medical system to earn the trust of First Nations. Canada is just a generation away from the forced assimilation and institutionalization of residential schools, along with segregated Indian hospitals that left a legacy of mistreatment.

This history was addressed by the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Medicine, in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action.

“It is undeniable that the health care system provided subpar to non-existent medical care to Indigenous peoples during the time of residential schools and Indian hospitals, and effectively failed them,” stated the faculty in a document released by UBC. “Today, Indigenous peoples continue to experience health inequities with devastating, often tragic, negative impacts on Indigenous health and wellness.”

In 2020 the province commissioned an independent review of how Indigenous people are being treated in the medical system. Led by former judge Dr. Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, In Plain Sight cited widespread prejudice, systemic racism and a lack of cultural safety, resulting in a “range of negative impacts, harms and even death.”

Meanwhile, B.C.’s Indigenous people have higher rates of chronic conditions across a range of health categories. In 2021 the average life expectancy of a First Nations person in the province was 67.2 – a drop of six years since 2017 – compared to the B.C. average of 82, according to the First Nations Health Authority.

The need for consistent and attentive primary care was clear for Barbosa as she grew up in Port Alberni.

“I witnessed and heard stories from a lot of my family of really poor treatment in the medical system,” said the med student. “I wanted to be a person for Nuu-chah-nulth people that was safe - and to try and help and prevent, give a space where people didn’t have to be scared of medical treatment.”

Despite this motivation, she admits that aiming for medical school was intimidating.

“I think the biggest challenge was working up the courage to apply in the first place, feeling like I wouldn’t be able to do it or be successful,” said Barbosa. “Having had done an undergraduate degree and felt that isolation from my community, knowing I was going to have to do it again was hard.”

Funding for school costs are being covered by the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, while scholarships have helped with living expenses in while studying in Victoria and Duncan. Even so, Barbosa spent a few years prior putting away money for school, relying on family to save on rent.

“For one of the years I lived with my grandma, so I put away three quarters of my income that year,” she said. “The next I was living with my now husband and just splitting costs, and we were able to save a lot.”

While it can seem like a tough hill to climb, those who gain credentials in a medical profession are in high demand. For nursing, Canada’s labour market conditions until 2031 cite a “strong risk of shortage”

“There continues to be acute labour shortages, affecting the delivery of health care services in various parts of the province, especially in rural areas,” stated a Canada Job Bank report from the end of 2024.

As manager of the NTC’s Community Health Services, Dr. Roger Boyer encourages Nuu-chah-nulth who want to help their communities to look at licenced practical nurse training, as most of this education can now be provided online.

“We need to encourage Nuu-chah-nulth to go into the LPN program, because you don’t have to leave your community – only for your practicum to do that,” he said.