Children playing “Tla-o-qui-aht warriors” paddled in cardboard cutouts of dugout canoes around the wooden pirate ship play structure at Tofino’s Village Green to recount the fate of the Tonquin. The 269-ton American trade ship sank to the bottom of Clayoquot Sound in 1811 after being overwhelmed by the warriors – and blew up.

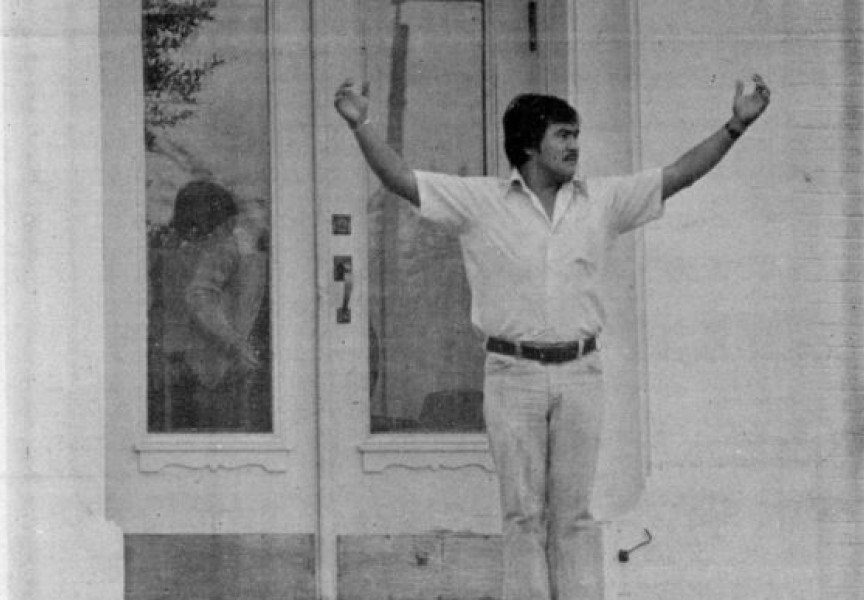

As told by Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation’s Gisele Martin and her father Joe Martin on June 11, the Tonquin’s goal was to establish a trade post and claim the region as part of the United States of America. The Tonquin’s captain Jonathan Thorn, who was played by Tofino resident Hugo Hall, was brash, and not well-liked by his crew. Thorn wanted to trade for sea otter furs with Gisele’s great, great grandfather Nookmis. But when Nookmis told him the price for one pelt was three blankets, 30 beads, 30 buckets and three knifes, Thorn scoffed and shoved the otter pelt in Nookmis’ face.

In the novel Astoria by American historian Washington Irving, which chronicles the entire journey of the Tonquin, Thorn is said to have “slapped” the chief in the face.

The next day, angry Tla-o-qui-aht warriors boarded the ship and threw the captain overboard.

“The captain got clubbed by the women and disappeared under water,” Gisele regaled the audience on the sunny June 11 afternoon.

One crew member, James Lewis, who was played by Clayoquot Action’s Dan Lewis, allegedly scuttled to the bottom of the ship and lit five tons of gun powder.

“KA-BOOM!” Joe exclaimed as the children ran around the mock Tonquin ship with sparklers. “Sparks flew and Nookmis got thrown overboard.”

Tonquin’s crew and roughly 100 brave Tla-o-qui-aht warriors perished in the sea. Martin says Lewis became the first “suicide bomber” of Clayoquot Sound.

“People in Opitsaht could see the mass of the ship for three years poking out of the water. During that time, Tla-o-qui-aht became very diligent about protecting this coast,” said Gisele.

It wasn’t until 20 years later that Tla-o-qui-aht started having a relationship with some of the British trading companies.

“That’s why Tofino is here today and that’s also why this is not part of the United States today. We’ve never sold this land. We’ve never ceded it; we’ve never signed it away in a treaty,” said Gisele, noting Tla-o-qui-aht’s fight to protect Meares Island from old growth logging, preserving the source of Tofino’s drinking water. “[I]n 1984 Tla-o-qui-aht took the government all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. In their own courts, the government could not prove that they owned this land.”

Forty-one years ago, Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, with support from the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council (NTC), famously declared Meares Island the “Wanachis Hilth-huu-is Tribal Park” under Nuu-chah-nulth law.

The Meares Declaration protected the old-growth forest from being logged, and is recognized as one of the largest demonstrations of civil disobedience in North America. Prior to the conservation stance, there was no “tribal park” in existence under provincial or federal legislation.

The wreck of the Tonquin was never found… But one day in the spring of 2000, a local crab fisherman found his trap hooked on the end of an old, old anchor – that anchor, encrusted with blue trading beads, is believed to be the Tonquin’s.

The anchor is on display at the Village Green in the gazebo to this day and belongs to the Tla-o-qui-aht.