This past summer, a 14-year-old boy hung himself in the rural First Nations community of Pacheedaht on the southwest coast of Vancouver Island.

“It was the saddest, saddest thing ever,” said Pacheedaht Chief Councillor Arliss Jones. “He was just an innocent little kid. The youth are still really hurt about him.”

Suicide deaths in Pacheedaht are high, says Jones. It’s a grim reality many Indigenous (First Nations/Métis/Inuit) communities in British Columbia face; a new B.C. coroner panel report shows Indigenous youth and young adults are disproportionately overrepresented among those who die by suicide in B.C.

The report says it is “inextricably linked to colonialization and the multi-generational trauma, racism and discrimination brought to bear by the residential school system and other such structures.”

“We just need to embrace our children and raise them in a different way than we were raised because it’s not working,” said Jones.

The panel reviewed the deaths of 435 young people in B.C. between the ages of nine and 25 who died as a result of suicide between Jan. 1, 2019, and Dec. 31, 2023. Suicide is the second most prevalent cause of death among children and youth in B.C., and the third-leading cause of death among adults aged 19 to 29 years.

In comparison, during the previous five-year period (2014 to 2018), there were 381 suicide deaths, an average of 76 deaths annually.

Ryan Panton, chair of the panel report, emphasized that the number of deaths by suicide should not be correlated with the state of mental health in B.C.

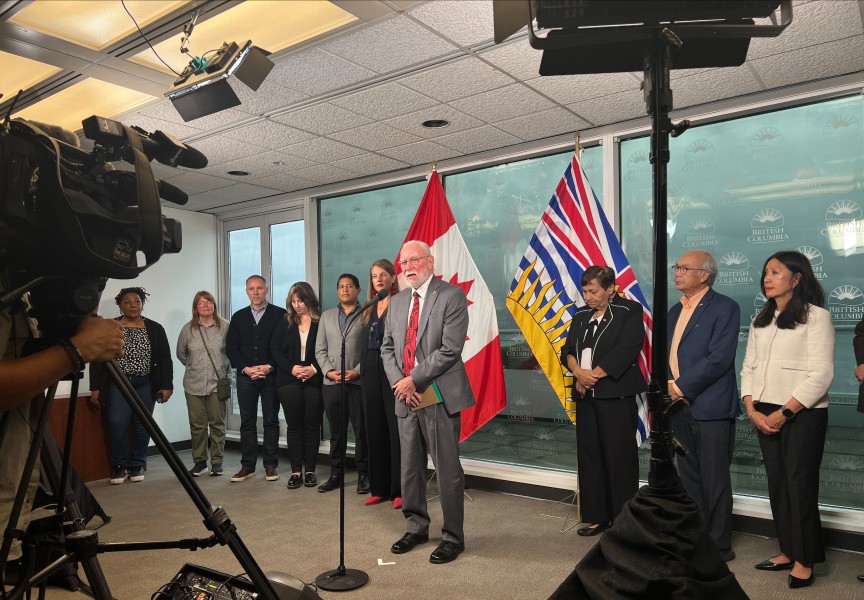

“This is a very trying time to be young in this province,” said Panton at an Oct. 15 media event.

The report lists five recommendations intended to prevent future deaths and improve public health for youth and young adults in B.C., including implementing a provincial suicide-risk-reduction framework specifically focused on youth and young adults.

It also calls for improved data collection, information sharing and reporting, and to review existing health-related resources to ensure they meet the diverse needs of school-age students.

It says training of medical professionals should include early identification, assessment and follow-up of young people who may be at higher risk of death by suicide.

The last recommendation is to leverage current spaces owned or leased by the province to use as safe places for young people to gather and connect.

“Communal spaces are limited for many young people, particularly but not exclusively for those in rural and remote communities,” said Panton.

Pacheedaht’s mini youth centre to open on Halloween

Jones shared that Pacheedaht had just completed renovations to the basement of a run-down old house into a mini youth centre. The nation kitted the space out with two TVs, an Xbox and baking supplies so the youth could do bake sales.

“It’s so they have somewhere to go,” said Jones, adding that the space officially opens on Halloween.

Jones says Pacheedaht is also capacity building for hunting by hand selecting young applicants for big game tags, like elk, and things like day trips out of community to fairs or participating in annual tribal journeys give the youth something to focus on.

“We need to get the kids out on the land and put the phone down for a couple hours and be present,” said Jones.

With respect to the potential harm of screen time, Panton said the “conversation was inconclusive” and that only a small number of deaths reviewed were related to social media.

“There are definitely concerns about some of the dangers of online use, particularly unsupervised online use when it comes to younger folks, but there is also an acknowledgement that this is a place where young people often find support and connection,” said Panton.

“Sometimes these connection points can be positive,” he said.

B.C.’s Chief Coroner Dr. Jatinder Baidwan noted that the Coroner Service investigates those types of deaths on a case-by-case basis and said they would “absolutely consider doing an inquest”.

There are about 40 children from kindergarten to Grade 12 living on traditional Pacheedaht territory, according to Jones. She says many of those kids spend three hours a day on a school bus to attend school in Sooke.

“The kids don’t want to do homework because they are on a bus for three hours a day,” said Jones.

She said the school district recently met with Pacheedaht about building a new community school on reserve lands. Pacheedaht qualifies for a new school, according to Jones, as she listed off their need to bring a classroom closer to home: High drop-out rates, low graduation rates, high suicide rates, high addiction rates, no sports and recreation, alcoholism and drugs.

“Yesterday was the first time that the (school district) really started to listen to our needs,” she said.

Other major findings from the report included 66 per cent of decedents were assigned as male at birth and that there were higher rates of death in the Northern and Island Health Authorities. Almost half of the decedents (52 per cent) had an MSP billing for a mental health issue and/or a suicide attempt in the year prior to death. Fifty per cent of the youth under 19 who died by suicide were involved with the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) in the year preceding their death.

About 10 years ago, Jones’ son was one of three Pacheedaht members to commit suicide. Her son was 29 years old at the time of his death and had two children. Jones says her son, who was an alcoholic, was trying to get help, but found “it impossible to get men’s resources.”

“My son found the second one that had passed away. He could not get that picture out of his head. He was already hurt. He just couldn’t recover from that,” she said.

Dr. Baidwan says, “there is a tremendous commitment from the government to do the right thing” when it comes to implementing the recommendations.

Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s (NTC) Teechuktl Mental Health provides clinical counselling and child and youth counselling within Nuu-chah-nulth communities. They also have counsellors on-site at the NTC office on Redford Street in Port Alberni. Teechuktl’s harm reduction team offers calm and steady support in the time of crisis, without judgement.

KUU-US Crisis and Care Society offers 24-hour support to individuals in the Port Alberni area and Indigenous communities across British Columbia. If you or someone you know is facing a difficult situation, call toll free 1-800-588-8717.

In an emergency, call 9-1-1, or go to a hospital emergency room.

In a crisis, call 1-800-SUICIDE at 1-800-784-2433 or 9-8-8 anytime of the day or night.