The First Nations Health Authority has released its latest numbers on the opioid crisis — overdoses and fatalities — data indicating a widening gap in an already disproportionate impact on Indigenous populations.

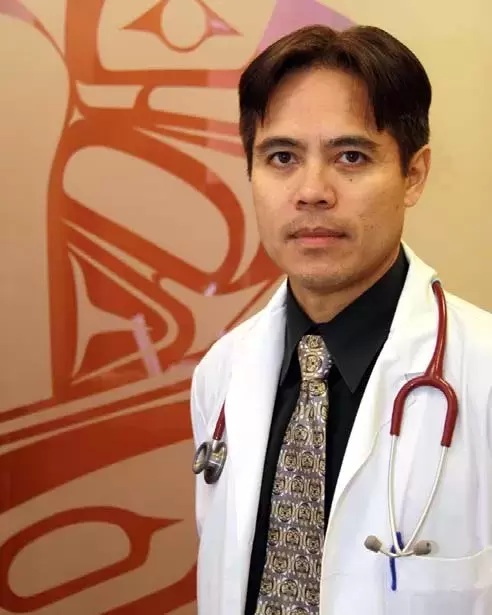

“This isn’t just data,” said Dr. Evan Adams, FNHA’s chief medical officer. “These are the lives of our family members. There must be more that we can do. The gap between non-First Nations and First Nations is wide and it’s getting wider.”

Grand Chief Doug Kelly, First Nations Health Council chairman, Dr. Bonnie Henry, provincial health officer, and Lisa Lapointe, chief coroner, joined Adams at a Monday news conference to make an impassioned plea for more resources and harm reduction strategies, specifically drug decriminalization and increased access to addiction treatment.

“We can do better, and we need to do better,” said Dr. Henry, who only last month called on the provincial government to decriminalize drugs for personal use. “We need to be there on all parts of that journey.”

Henry contends, along with many who work in health and addictions, that decriminalization would reduce the harms of addiction by removing barriers to treatment. Her plea was rejected outright by the province.

Last year, 193 First Nations men and women died of overdoses in B.C., an alarming 21 percent increase over 2017. First Nations represented 13 percent of fatal overdoses, an 11 percent increase in just one year.

The 2018 figures serve as a finger on the pulse of an overdose epidemic that shows no sign of abating. B.C. is in the third year of a provincial health emergency that has mobilized resources and saved many lives, yet fatal and nonfatal overdoses continue at a staggering pace, taxing first responders and the health-care system itself.

From the start, First Nations were over-represented. In 2015, First Nations were three times more likely to die of an overdose than the rest of the population. Last year, that number rose to 4.2. The increase occurred as the overall mortality rates in B.C. show signs of levelling off or dropping.

Syexwaliya (Ann Whonnock), a Squamish Nation elder, delivered a prayer and welcoming ceremony at the news conference while sharing her personal tragedy, losing her son last year to an overdose. She believes he may have survived with proper access to support services.

Kelly said the “cold hard facts” show an urgent need for changes, changes in legislation and changes in attitude among all community members. Only last week, FNHA and the provincial government announced a $40-million investment to revitalize two First Nations-run treatment centres and build six more, he noted.

“Because of the complex underlying causes that result in First Nations’ over-representation in this crisis, increased resources and efforts are needed to address the widening gap between the general population and First Nations,” he said.

As the body of research grows, another distressing disparity has emerged. In the general population, about 20 percent of deaths occur among women. For First Nations, the figure is 39 percent. Much more is revealed than the death toll, however.

“We also know from our research that almost half of those who died over the last three years had sought supports for pain … from traditional medical methods,” Lapointe said. “I think that should give us pause for thought. These are not criminals. These are people who are struggling for support.”

More research is needed to understand precise causes of disparities. Cultural and systemic factors are all too familiar, the story behind what Adams, a Coast Salish physician, termed “race-based outcomes.” He listed colonization, lack of access to safe spaces, childhood trauma (an underlying cause of addiction) and intergenerational trauma in addition to the continual plight of marginalized populations.

First Nations women are incarcerated disproportionately just as First Nations children are over-represented in child welfare, Kelly observed.

“There’s not a lot of help out there right now,” Lapointe said. “There’s a lot of stigma. There’s a lot of marginalization. Authority, frankly, has not been kind to First Nations people, First Nations women.”

She said it’s essential that society build a path to dispel fears and build trust, “to ensure that treatment afforded is compassionate and nonjudgmental.”

Echoing Henry’s appeal for drug decriminalization, Kelly put the crisis into human terms.

“Why is it we can do that with marijuana when we can’t do it when it’s killing people,” he asked.

People who are suffering addiction need compassion, not condemnation, Kelly said. Instead of asking, “What’s wrong with you,” ask them “What happened to you?

“We need to change our strategies. We need to move to compassionate leadership, and leadership is not confined to those who are elected, thank God.”

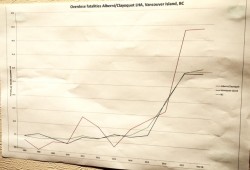

Fifty people have died in the Alberni Valley from overdoses in the last decade, but the city was not listed by the FNHA among “hot spots” in the opioid crisis, a list that includes Campbell River and Kamloops. Figures released in February by VIHA show overdose fatalities in the Alberni-Clayoquot health area far exceed B.C. and Island rates when measured by population.