The passenger boat sliced dense coastal fog on the early morning ride to Hot Springs Cove, but by time family, friends and guests stepped foot on the village dock, the sun was breaking.

Wearing two shades of pink, grey pants and a ponytail, Hesquiaht First Nation’s (HFN) elected Chief Councillor Mariah Charleson (łučinƛcuta), 36, greeted her visitors warmly at the entrance of the school as a mound of freshly knifed sockeye sat ready for the grill.

“As Hesquiaht people, we have been self-sustaining for thousands of years. This opening of the project signifies that transformation and we’re really happy that everyone was able to make it here for the celebration,” said Charleson, who now lives in her childhood home in Hot Springs Cove.

Aug. 8 marked a milestone day for the little community of about 55 people, as they celebrated the culmination of Ah’ta’apq Creek Hydropower, a renewable energy project that spent nearly 20 years on the shelves. After finally getting greenlit, it was almost quashed due to pandemic restrictions. Dignitaries from the Government of Canada, the Province of British Columbia and the Fraser Basin Council made the journey to the isolated village, located north of Tofino on Vancouver Island, as well as project team members from the Barkley Project Group, Redd Fish Restoration, Speers Construction and Hakai Energy Solutions.

Hot Springs Cove is not connected to the B.C. Hydro grid and, until recently, the village relied on diesel generators for all electricity. Carrying a flashlight was the norm with the generator turning-off at midnight and rumbling back-on at 6 a.m.

But as of November 2021, HFN successfully weaned off diesel generators with a 350-kilowatt run-of-river hydropower and solar microgrid that is 100 per cent owned by the First Nation. The renewable energy infrastructure has since dramatically reduced the nation’s dependence on diesel fuel consumption, improved their environmental footprint and created a savings of $375,000 in diesel bills in the first year alone.

“We are transforming into a better way of doing things,” said Charleson. “This is a blueprint that other First Nations, not only in British Columbia, but all across Canada, can now follow because of everybody in this room. It’s because all the different partners who have decided that this is a positive initiative this is a step in the right direction. This is absolutely huge in moving us forward in the right way when we talk about that word reconciliation.”

B.C. Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation Minister Josie Osborne gave a speech at the celebration. She acknowledged Hesquiaht’s hereditary chiefs and the Hesquiaht people for being stewards of the land for thousands of years and expressed pride in being part of a government that believes in Indigenous-led clean energy projects.

“That’s the way forward. Moving forward we can only do business in a way that is Indigenous-led and that has Indigenous stakes and equity in these projects,” said Osborne, who was a fisheries biologist for the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council before entering politics.

Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) echoed the sentiment.

“I hope in years to come we will be able to see other projects to fruition in your community. I hope this is one project of many more to come. Thanks for having us and thanks so much for welcoming us with open arms. It’s been a treat and a privilege,” said Averil Lamont, director of community infrastructure for ISC.

How Ah’ta’apq Creek Hydropower works

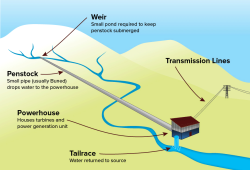

Five pick-up trucks took the group up a bumpy, 2.5-kilometre gravel access road to view the water intake structure, comprised of a weir and a concrete inlet structure.

“We all did our fair share of working on the road,” Hesquiaht maintenance crew Richard Lucas said on the drive.

The intake collects water from seven streams, and when the rain comes in September, the water flows through 2.3 kilometres of large pipe to the powerhouse. This produces enough energy to displace 75 per cent of the community’s diesel-generated electricity.

“When it rains, the power can go for days and days,” Lucas said, adding that he pays about $30 a month for the electricity.

To help fill the gap when the weather is dry, HFN interconnected a 133-kilowatt solar photovoltaic (PV) system, so they don’t have to go back to relying solely on diesel. Hakai Energy Solutions installed the solar panels on the gymnasium roof top, and they have a lifespan of about 30 years.

Honouring late chief councillor Richard Lucas

A commemorative plaque for late chief councillor Richard Lucas, a lifelong champion of the clean energy project, will go in the powerhouse.

“This project meant the world to Richard,” said HFN Executive Manager Norma Guerin-Bird.

Members of his direct family were wrapped with blankets as a reminder of the important work Lucas did for the village of Hot Springs Cove.

“I hope on days that you might be having a tough time, that they are a reminder of the strength that comes directly for your family; the strength that he gave our community that we can continue on… And I hope that it’s reminder for you to come home,” said Charleson.

After the Good Friday 1964 Tsunami destroyed most of the housing in Hot Springs Cove, many Hesquiaht families relocated to Port Alberni.

“A big thank you to all of you for you’ve been able to complete for this community. This gives my wife and I more of a desire now to be home than in Port Alberni,” said elder Linus Lucas. “What you’ve done here is created a place for us to feel safe 24-hours a day.”

Ah’ta’apq Creek Hydroelectric Project won the Award of Excellence in the 2023 of Excellence ACEC-BC (Association of Consulting Engineering Companies British Columbia), Energy and Industry category.

The multi-million-dollar project had six funding partners: Natural Resources Canada’s Clean Energy for Rural and Remote Communities program, Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program Rural and Northern Communities stream, Fraser Basin Council’s Remote and Indigenous Communities Clean Energy Program, Indigenous Services Canada, BC First Nations Clean Energy Business Fund and BC Rural Dividend Fund.