In October the Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' First Nations marked a historic development in their government, with the first time hereditary positions have been changed to their legislature since the Maa-nulth treaty was implemented over 14 years ago.

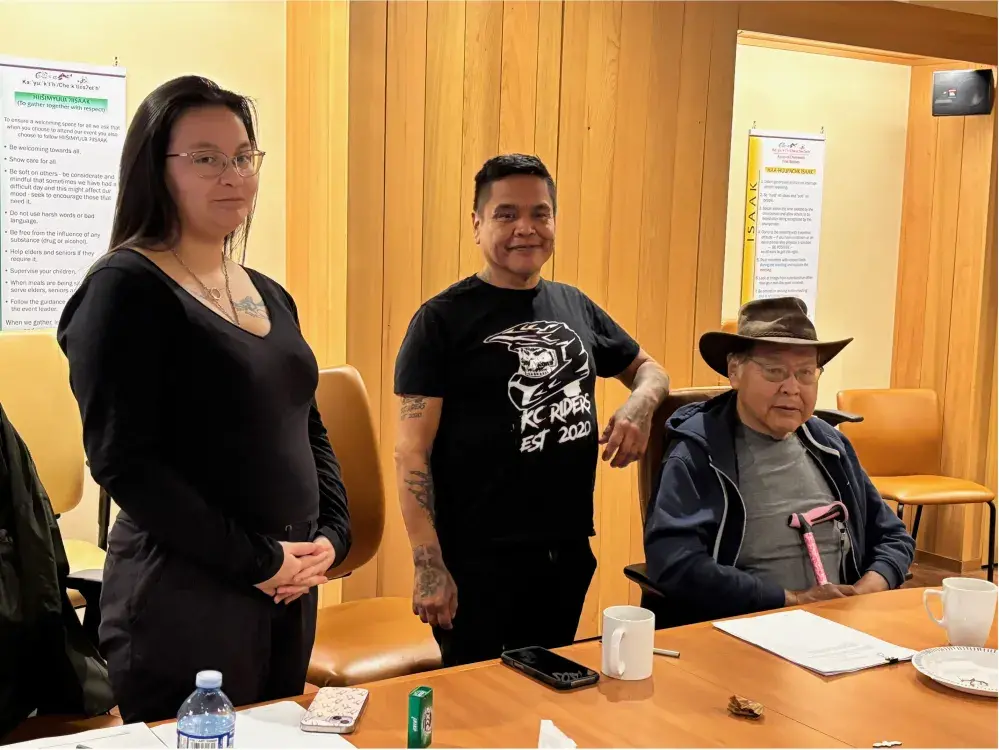

On Oct. 17 two of the four ha’wiih positions on the First Nation’s legislature saw new representation, with the swearing in of Ha’wilth Maxine Dragon Gillette and Ha’wilth Anthony Oscar, two hereditary leaders representing the Che:k'tles7et'h' nation. Maxine Gillette was formally seated as the Tyee of Che:k'tles7et'h' on Sept. 13, a title passed down from her father Francis Gillette. Then Anthony Oscar was seated as a Che:k'tles7et'h' Ha’wilth on Oct. 11 by his father William (Bill) Oscar.

“They’ve aged and handed their seats down to their children,” said KCFN Legislative Chairman Matthew Jack of the passing of the hereditary seats. “It’s the first time we’ve seen that with our new government.”

Since the Maa-nulth Final Agreement was implemented on April 1, 2011, the Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' First Nations have been led by a legislative body composed of an elected chief, four elected members and four ha’wiih, which include two hereditary chiefs from Ka:'yu:'k't'h' and two from Che:k'tles7et'h'. These hereditary positions on the legislature are appointed by a Ha’wiih Advisory Council, according to the First Nation’s laws. The other two hereditary positions on the legislature are currently being held by Tyee Ha’wilth Samantha Christiansen and Ha’wilth Valerie Hansen from the Ka:'yu:'k't'h' nation.

The legislature meets every month to vote on major decisions facing KCFN. Elected on April 18, 2023, Benjamin Gillette is the legislative chief, joined by fellow elected members Lillian Jack, Devon Hansen, Larissa Hansen and Matthew Jack.

A stipulation in the Maa-nulth treaty ensures that Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' governance will include hereditary representation.

“The legislative Ha’wiih, as members of the Legislature, have the same powers and responsibilities as the elected members of the Legislature as set out in Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/Che:k’tles7et’h’ law,” states the KCFN Government Act.

“That way we can incorporate our traditional values and stuff into the modern government,” explained Matthew Jack.

With just under 600 members, Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' territory stretches far across the shores of northwestern Vancouver Island, from Porrit Creek in the south to Solander Island at the tip of Brooks Peninsula. After their populations were decimated by disease during European settlement on the west coast, the two tribes merged in the early 1960s, bringing Kyuquot Sound and Checleset Bay into the First Nations collective Ḥahahuułi.

Traditionally, each chiefly family is responsible for a stream, inlet, island or natural feature within this territory.

“For modern treaty nations, modern self-governing nations, we felt that it was important that we keep that cultural aspect of our ha’wiih so they can help in our ruling and creating our laws,” said Jack.

One of British Columbia’s few modern-day treaties, the Maa-nulth Final Agreement also includes the Uchucklesaht, Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ, Toquaht and Huu-ay-aht First Nations. It enables these Indigenous communities to be entirely self-governing under Canadian law, removing them from the conditions of the Indian Act.