The newly passed federal budget includes language to “wind down research”, “scale back” some programs and “reduce management layers” within Fisheries and Oceans Canada – part of plans to cut half a billion in the department’s expenses over the next four years.

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s first budget passed an evening vote on Nov. 17 by a close margin of 170-168, saving the Liberals from a confidence motion that would have triggered an election just months after the minority government was formed in the spring. Four MPs abstained from the vote to enable the budget to pass, including two each from the Conservatives and NDP. Courtenay-Alberni MP Gord Johns was among those who abstained, whose NDP party refused to support the budget while stating that now is not the right time for another election amid the economic uncertainty facing the country.

Interim NDP Leader Don Davies stated that the spending plan “fails to meet the moment” that Canadians are facing.

“While there are elements of the budget which reflect our concerns, on the whole it is a conservative budget,” he said in a release, noting that it’s also clear that Canadian do not want an election right now. “The consequence of defeating this budget would not be to improve it or to help Canadians. It would be to plunge the country into an election only months after the last one, and while we still face an existential threat from the Trump administration.”

Under a $78.3 billion deficit projected for this year, on Nov. 4 the Liberals introduced the plan as “an investment budget” that spends more on “nation-building” infrastructure and less on government operations. The $500 million in cuts to DFO programs and services over the next four years are part of a larger plan to reduce Canada’s civil service by 16,000 positions.

This year Fisheries and Oceans Canada has an annual budget of $6.05 billion, with the equivalent of 14,747 full-time staff. In recent years DFO has benefitted from a steady increase in overall funding, growing from $3.78 billion over the 2022-23 fiscal year, but this spending on the department’s “core responsibilities and internal services” is now projected to decline to under $5 billion by 2028.

“To meet up to 15 per cent savings targets over three years, the Department of Fisheries and oceans will wind down research and monitoring activities that have either achieved their objectives or for which alternative data sources exist, scale back certain policy and program capabilities, reduce management layers, and right-size internal services,” states the Government of Canada.

And what does “right size” mean? This terminology leads to the expanded use of artificial intelligence to “modernize Canada’s fisheries management system”.

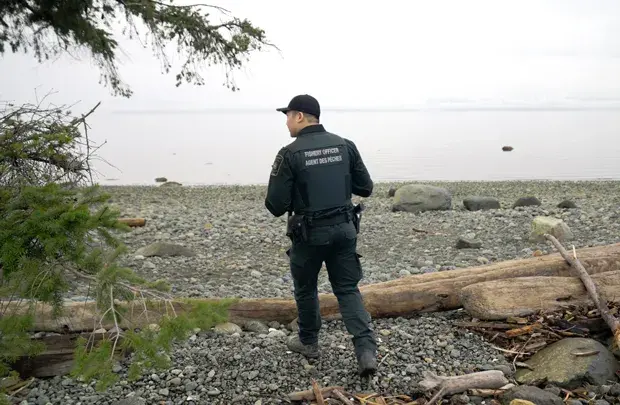

“Reducing the use of burdensome paper-based tools will free up time for fisheries officers to spend in communities and on the water enforcing fisheries regulations,” states the budget.

Covering the country’s three coasts, DFO’s mandate includes fisheries management, supporting aquatic ecosystems, marine navigation and the Canadian Coast Guard. Over the past three years fisheries spending has dramatically increased, growing from $1.08 billion in 2022-23 to $1.41billion this year with 3,848 dedicated staff. But funds allocated for fisheries management are set to drop to $744 million in the 2027-28 fiscal year.

Back in June, while addressing the Nuu-chah-nulth Council of Ha’wiih Forum on Fisheries, a long-serving DFO biologist spoke of the approaching fiscal restraints facing the federal department. As section head for Aquatic Ecosystems and Marine Science, Sean MacConnachie presented survey data illustrating the exponential growth of sea otter populations across the B.C. coast – a phenomenon that many Nuu-chah-nulth leaders see as a threat to shellfish. Since 1977 DFO has conducted widescale counts of the voracious pinnipeds, but funding for such measures is uncertain.

“A good chunk of that funding is up for renewal at the end of this fiscal year with the Nature Legacy funding,” explained MacConnachie. “As we all know, we have a new government and the prime minster is setting new priorities, including a cap to the public service. There’s going to be lots of changes in my staff.”

With 27 years in DFO, MacConnachie reflected on future limitations to monitoring if the federal department is forced to tighten its spending. Sea otters will continue to grow across the coast, and have recently been found as far south as Neah Bay in Washington State, but the biologist admitted that his team does not have the resources to do an entire population-wide survey. He thanked Nuu-chah-nulth representatives for contributing data to what DFO is able to gather on sea otters, or kwakwat in Nuu-chah-nulth.

“My ability as a manager of that program to be able to hire or rehire is going to be really, really difficult,” he said. “I don’t know how I’m going to manage the science for this, given what will change.”