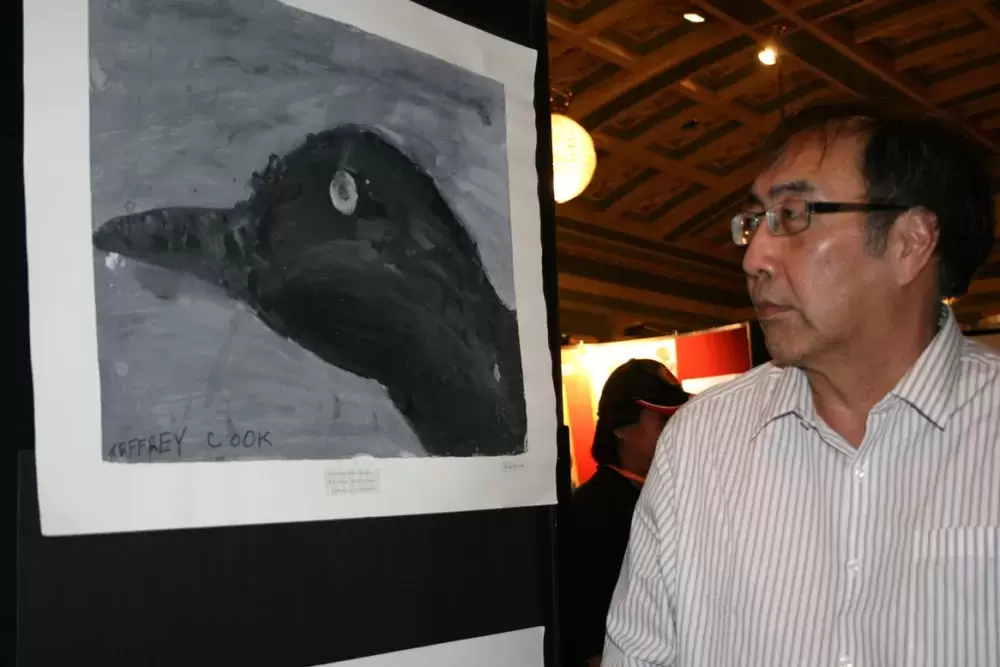

Huu-ay-aht Chief Councillor Jeff Cook was surprised to learn that after about 40 years since he had left Alberni Indian Residential School something from his time there had survived— a 16 by 20 inch painting he did of a black bird against a grey background.

The painting was one of 47 that made up an exhibit on display at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s regional event held April 13 and April 14 in Victoria. The children’s art was produced at AIRS from 1958 to 1960, preserved and documented by art teacher Robert Aller.

Aller visited the school once a week over those two years, pushed aside the desks, designed to keep the kids immobile and sitting straight, and set the students up around the floor space with paper and poster paint.

Pictures of some of the work at: http://www.hashilthsa.com/gallery/art-work-children-alberni-indian-residential-school

The result of this unaccustomed creative freedom was a series of artwork that depict scenes from home, of the nature the children saw around them, and of important cultural symbols of the communities from which the children were removed all that time ago.

As part of his lessons, Aller had asked the children to each provide a painting for him to keep. He cared for those paintings, and when he passed away, Aller’s family bequeathed them to the University of Victoria, along with his papers and important documents.

The paintings were danced into the exhibit space at The Empress Hotel in Victoria on April 12 by 47 Nuu-chah-nulth women. The floor had been cleansed by the Coast Salish and Tim Sutherland sang a prayer chant before the men sang the Nuu-chah-nulth Song. And then the victory song was sung, because the exhibit was a victory of survival, said Cook.

April 12 was the first time he had seen the painting, though he doesn’t remember making it. In fact, he didn’t remember Aller at all. But he was grateful that the painting exists.

“Our generation never got to save stuff,” he said. Cook admits that he saves everything now, no matter the significance of the item.

A lot of people today take for granted the mementos of school life; things collected by parents to keep and pass along to their children and grandchildren to remember days gone by. But former residential school students likely haven’t much from that time except for the memory of their experiences, explained Cook. He was at AIRS from 1956 to 1970, going home each summer for two months.

Art wasn’t really Cook’s escape from day-to-day life in the school. Soccer was, Cook explained. He could get away from the school on Saturdays to play teams in town or from other residential schools, like Kuper Island.

While many students at AIRS were terribly mistreated in the school, Cook said he did not see any of the abuses, though he did get strapped from time to time.

Cook was the only artist at the launch of the exhibit, but he recognized the names of the others, including Harry Williams, Stewart Joseph and Robert Dennis.

He said the exhibit gave him strength.

“A lot of us survived.”

Dr. Andrea Walsh, a visual anthropologist who specializes in 20th century and contemporary aboriginal art at UVic, is responsible for the collection. She worked with Robina Thomas of Lyackson, an Associate Professor in Social Work at the University of Victoria, along with elders and survivors, on preparing the exhibit for the TRC event.

When they were thinking of bringing out some of the painting, the elders told them that all of the painting from AIRS should be shown as a unit because “you can’t separate (the students) again,” Walsh said. Aller also left a collection of student paintings from MacKay residential school in Dauphin, Man., and there is hope that an exhibit of children’s art from other residential schools can be found to create a larger exhibit in the future.

Thomas has made it her life’s work to understand the residential school experience, even sitting with Art Thompson through his court proceedings, the first survivor to take the churches and Canada to court to hold them accountable for the abuses at Alberni Indian Residential School.

When Thomas looks over the paintings she sees the emotion the children were able to express. One child drew a copper shield, another drew a thunderbird with a whale in its talons. Other paintings were dark and abstract. Still others were funny and colorful.

To Thomas, in their own ways, the children were demonstrating resistance by telling stories about their culture, their people, their communities and their suffering.

Walsh says she views the pictures through the techniques being applied. She points out one painting of an owl and says she can see the pressure the artist was using on her brush as it went across the page to paint the background. She wondered what the artist was dealing with to apply such pressure and to use so much paint.

Robert Aller was an accomplished artist in his own right, said Walsh, even leaving many works with Port Alberni’s Rollin Art Gallery. He had a difficult upbringing, impoverished and abused, so he developed a lot of compassion for the children of AIRS, even attempting to raise the issues of the conditions in the schools with his peers and through public talks.

At one point he writes “all is not well with the country.” He encouraged his peers to get to know about the Aboriginal condition and to read such books as Harold Cardinal’s The Unjust Society.

The children’s art is an important collection that Walsh hopes to bring to Port Alberni in the near future. But for many family members of the artists, the collection allows them to stand in the space of the child that would become their mother or father, grandmother or grandfather.