The West Coast General Hospital is taking steps to make itself more accessible to the community’s more vulnerable, including First Nations patients who struggle to get the services they need, according to its chief of staff.

Dr. Sam Williams spoke of the hospital’s ongoing efforts during a panel discussion on mental health Wednesday, part of the NTC’s Disability Access Committee’s Health-Ability Fair.

“We are trying very hard in our emergency room to improve the care that we are giving to our most vulnerable patients, she said. “We are halfway through - with the help of many elders from the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council - to provide accommodations and put in place real change in our emergency so that when you come, we are treating you with kindness, cultural humility and real knowledge and curiosity with our dealing in trauma from the past.”

During the discussion Andy Callicum, vice-president of the tribal council, commented to the guest panel that many Nuu-chah-nulth people are having difficulty connecting with the medical support they need – particularly with respect to mental health issues.

“We’re finding that a lot of people struggle with articulating what’s going on in their lives,” said Callicum. “There are some doctors who are quite hands-off with mental health.”

“There needs to be some sort of extra help in there, people in place that could help go with people to doctor’s appointments and advocate for their client,” he added.

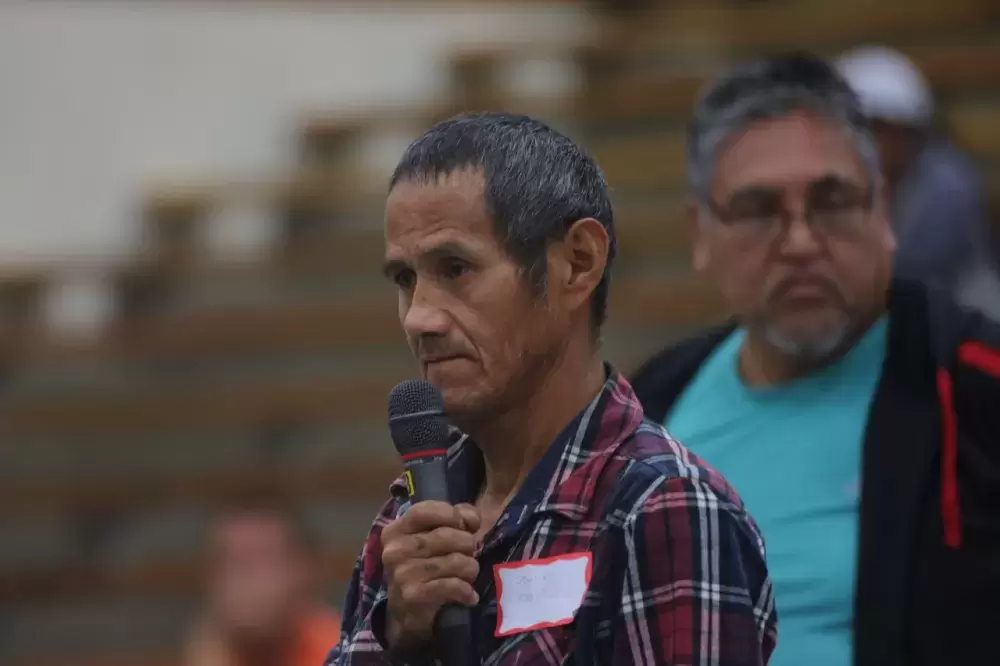

Stan Lucas, who is a member of the Hesquiaht First Nation, said that he never got the help he needed from Port Alberni’s hospital since he was hit by a car two years ago. Feeling the effects of a concussion, Lucas said he went to the emergency ward several times, but didn’t receive treatment due to the department being full.

“So I gave up,” explained Lucas, who instead used traditional medicine for his symptoms. “I don’t want to go to this hospital again and get turned away.”

“Up until a few years ago a lot of our people used the emergency ward at our hospital as a walk in clinic,” said Callicum. “Things have gotten a bit better with the walk in clinic hours in town… [but] there are quite a few of our most vulnerable people that live in this community who aren’t attached to a doctor.”

Williams stressed that additional support is now available through a nurse practitioner who can function as a physician. With additional training and experience, a nurse practitioner can automatically diagnose and treat illnesses, as well as order and interpret tests, prescribe medications and perform medical procedures.

“We have a nurse practitioner who works now in Port Alberni and is accepting new patients,” she said. “It’s hard to find a doctor in town - their practices are busy - a nurse practitioner is member of the medical staff that works independently.”

The long-term effects of traumatic experiences during childhood were discussed, an issue that affects Aboriginal communities more than previously believed, said Courtney Defriend, Ti’yuqtunat, regional manager for the First Nations Health Authority.

“Arthritis and diabetes, those are directly related to traumatic experiences,” she said.

“The first thing that people need when they experience trauma is safety,” added Margaret Bird, a psychologist working with the Quu’asa program.

Linus Lucas commented to the panel that he saw the impact of residential school in his father while receiving medical treatment in a hospital.

“My dad was a survivor of residential school. When I watched him in the hospital he didn’t want anybody to touch him if they weren’t First Nations,” Linus said. “He was left alone.”

The Hesquiaht member said his parents broke this cycle by relocating when he was young.

“My parents made a conscious decision for me not to enter residential school, so we moved here,” he said, adding that this affected how comfortable he feels with non-First Nations people. “My best friends are white, they’re East Indian, Chinese, Jehovah.”

“It made a big difference in how I was treated in the hospital as opposed to my dad,” he added. “And the irony of it is my dad was on the same floor that I was, we had the same nurses, the same doctors, but he was treated completely differently.”

The discomfort many First Nations people have felt with Canada’s medical system is addressed in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action, which requires the medical profession to “recognize the value of Aboriginal healing practices and use them in the treatment of Aboriginal patients in collaboration with Aboriginal healers and elders where requested by Aboriginal patients.”

“This is the way that we begin that journey to achieve the cultural humility that we need to do the paradigm shift that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission asked for,” said Williams. “There is no us and them; there is just us working together.”

The West Coast General Hospital’s nurse practitioner can be reached at 250-731-1313, then by pressing option 3.