From his younger years as a founder of the West Coast Warrior Society to a call for the province to eliminate discriminatory organ donation policies during the last year of his life, those closest to David Dennis will remember him for his fearlessness in the face of daunting adversity.

A member of the Huu-ay-aht First Nations and father of five, the 45-year-old was taken off life support on Friday, May 29, less than a year after being diagnosed with end-stage liver disease. His passing was acknowledged by the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, an organisation he formally served as Southern Region co-chair more than a decade ago.

“As we say goodbye to David, we remember him with fond memories, his moments of courage and his fighting spirit,” reads an NTC statement released today.

That fighting spirit became apparent to Terry Dorward when he first met Dennis in the late 1990s, a period he recalls as “the height of the Native Youth Movement, back when we were rallying against the B.C. treaty process.”

By 2000 Dorward, Dennis and three other members of the advocacy group’s security forces had broken off to form the West Coast Warrior Society, an organization that soon gained the attention of authorities for their militant appearance.

“Throughout ’97 and ’98 there were members within the Native Youth Movement who felt that we should take a more direct, assertive approach to title and rights,” explained Dennis, wearing combat-style camouflage in video footage from the time.

From B.C. to New Brunswick, the Warriors took part in blockades for Indigenous rights, and took to the water for the Cheam First Nation when the Department of Fisheries and Oceans blocked the community from fishing on the Fraser River. At this time recreation boats were permitted to fish in the First Nation’s territory, said Dorward.

“They felt that it was their right to fish, but they were getting hassled. Women and elders and youth were getting violently arrested,” he said. “They needed a security force to protect them while they set their nets out.”

This approach also came to Nuu-chah-nulth territory when the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation was having difficulty getting approval from Parks Canada to expand their reserve.

“We were ready to shut down the Tofino highway, we were out there training on the beaches,” recalled Dorward.

The pressure apparently worked, and the reserve expansion brought the new community of Ty-Histanis.

“Government officials, they listened,” said Dorward. “Indians in camouflage had a strong presence. It created a lot of uncertainty.”

But the Warriors also gained the attention of police. The pressure escalated to Dennis and two other members being stopped at gunpoint on Vancouver’s Burrard Street bridge in June 2005. Fourteen rifles and ammunition were seized, but Dennis contended that the weapons, which were legally purchased, were being transported to train Tsawataineuk youth to hunt on B.C.’s central coast. The Warriors were soon released without charges, but Dennis encountered threats to his family, and the group disbanded that summer.

Dennis’ advocacy came to the streets of Vancouver as well, where he became president of the Frank Paul Society, named after an Indigenous man who died during a cold night in late 1998 when he was taken into police custody. Paul was picked up by police for public intoxication, but was soon deposited in a downtown alley, where he died from exposure later that December night. The Frank Paul Society was committed to ensuring recommendations from an inquiry in Paul’s death were implemented, and pushed for sobering centres in Vancouver to protect those at risk.

Carol McCarthy, who birthed two and raised three children with Dennis, recalls her partner as someone with an “ability to see things from a different angle.” He showed a keen interest in bringing out people’s ancestral pride, recalled McCarthy.

“When he met people, he would ask, ‘Who’s your people?’,” she said. “He would tell them, ‘Don’t ever be afraid of being Indigenous’. I don’t think that many young people ever heard that in their life.”

She added that Dennis was also a dedicated father.

“He did a lot of stuff with the kids outdoors, like going to the park, playing football,” she said, “taking the kids out to go camping.”

But Dennis was aware of the personal cost of going against the tide of mainstream society, as shown during a talk he gave at an East-Vancouver location after his involvement with the Warriors.

“In my life, figures that I have respected, people that have stood up and taken a hard-line position on anything, have been affected on the personal side,” he said.

Possibly his most daunting challenge yet came with a liver disease diagnosis in July 2019. A roadblock in treatment options arose when Dennis was informed by BC Transplant that he would be excluded from the organ donor registry due to a policy requiring abstinence from alcohol for six months.

With the support of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs, a complaint was sent to the BC Human Rights Tribunal, claiming that the abstinence policy was discriminatory. Dennis, who had stopped drinking on June 4, was being unfairly judged for his alcohol use disorder by BC Transplant, under a policy with “little or no scientific support,” according to the complaint.

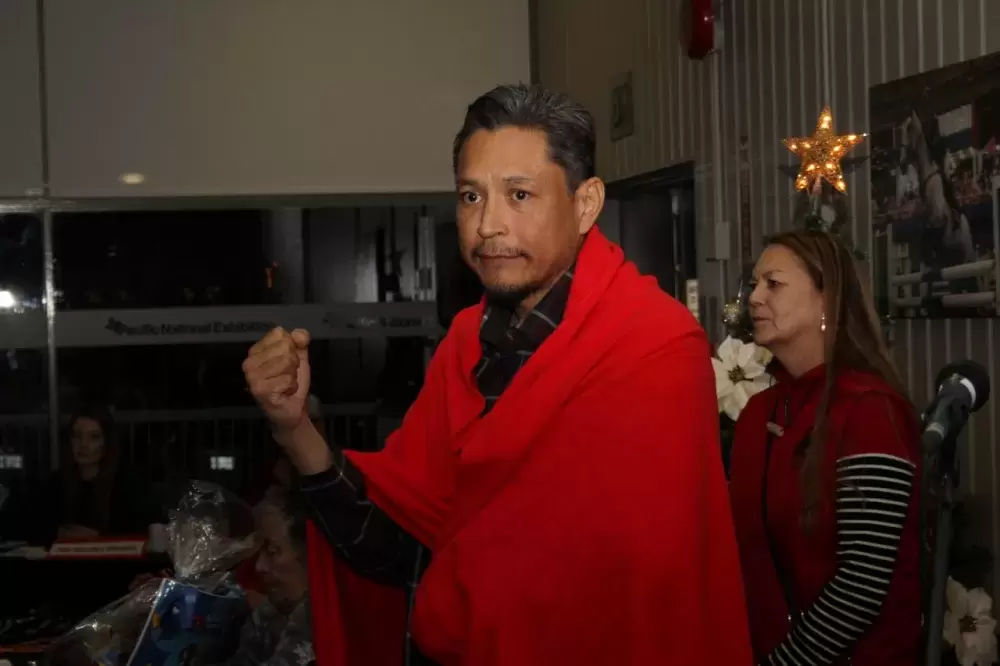

By September BC Transplant changed the six-month abstinence requirement, but Dennis’ condition had worsened to the point where it was unclear if his body could sustain a transplant. During a Nuu-chah-nulth Urban Gathering in Vancouver last December he spoke of the need to accept his condition, while citing how the change in policy will help others in the future.

“They’ve changed their stance, which will benefit ultimately a lot of our kuu’us people because they won’t be faced with the same barriers,” he said, celebrating six months of sobriety on the occasion.

“He let people know that it’s okay to be angry, it’s okay to be mad at the system and to channel that rage and to put it into something proactive,” recalled Dorward. “It created a lot of pride and he helped ignite that.”

While his last few months were filled with “excruciating pain”, McCarthy saw him suffer in order to spend more time with those closest to him.

“He was determined to do whatever he could to prolong his life,” she said. “I held him until he passed away.”