The wave of discoveries this summer of unmarked graves at residential schools sparked a distant memory in Bernard Jack. He recalls attending Christie Indian Residential School on Meares Island as a young child, where a gravesite could be seen outside of a church that students were taken to for services.

“All I seen was pegs at the end of a grave,” said Jack, who attended Christie from 1968-73.

“The other kids that had been there longer than us already [said], ‘Just look away, keep going’,” he continued. “We knew they were there. That’s one of the things that we did not talk about in the school. You would be really, really punished for that.”

A member of the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation, Jack was taken from his home in Yuquot on Nootka Island at the age of six. He thought he was going for short airplane ride, but his first trip in the air ended with Christie’s priests and nuns waiting at the dock.

“Not being able to speak English, and being strapped for that, that was the start of being punished for speaking your own tongue,” recalled Jack.

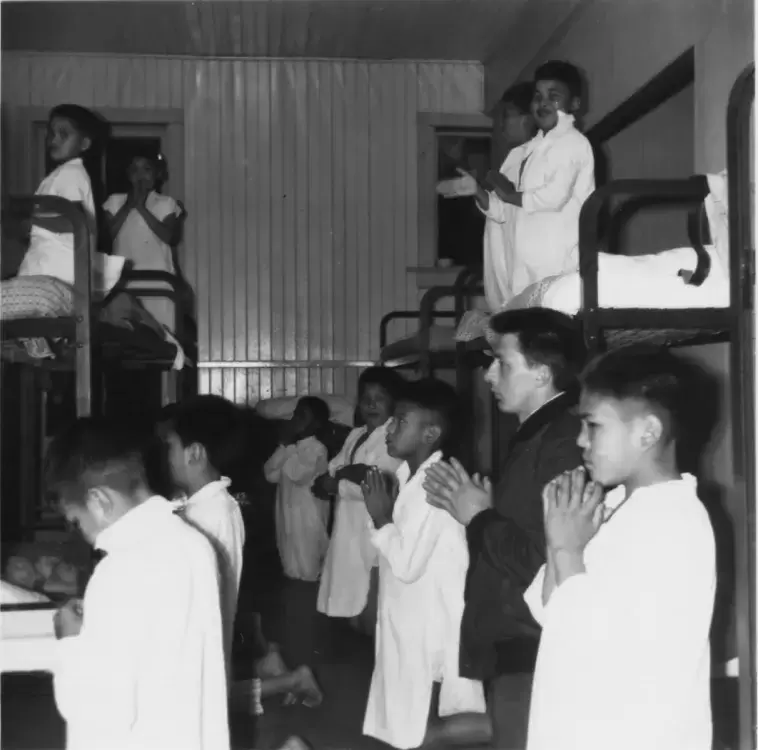

Over his time at the school a current of terror ran through the air, upheld by the constant abuse and sexual molestation Jack encountered. He remembers the bunk room, where at times children were being strapped at one end for wetting their beds, while at the other end sexual abuse was occurring.

“The kids deliberately wet their beds so that they could deal with the strapping [rather] than the molesting,” Jack said. “While they were screaming away, the other kids down the room were being molested. When the priests or nuns finished they would come up to the other kids that were being strapped. ‘You kids say anything, you guys are going to be next’.”

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, a total of 23 students died while at Christie, which operated from 1900-83. But Jack believes that far more students never returned home from the residential school.

For generations the deaths and abuse weren’t acknowledged – even among family members who attended residential schools, recalled Jack.

“They don’t want to talk about it,” he said. “It’s like opening up an old wound.”

But now this belief is being confirmed, starting with the discovery in late May of the remains of 215 children at the former site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School. Through ground penetrating radar, similar discoveries followed. In June the Cowessess First Nation in southern Saskatchewan uncovered 751 unmarked graves at a residential school on their land, then a week later the Lower Kootenay Indian Band announced the remains of 182 were found at the St. Eugene’s Mission School site. Most recently in mid July the Penelakut Tribe publicized the uncovering of 160 unmarked graves at the Kuper Island Residential School site east of Vancouver Island.

Work is underway in Nuu-chah-nulth territory, with the Tseshaht investigating the grounds of the Alberni Indian Residential School, while the Ahousaht First Nation is looking into former sites on Flores Island and where the Christie school once stood, calling on the provincial and federal governments for assistance – with hope that the remains of some of the lost children might one day be returned home.

“Stories are shared of children who died while at these schools and parents were not told the reasoning for the death,” stated the Ahousaht First Nation in press release. “Other stories share that babies were born to children at the school and the babies were not seen after birth.”

Richard Watts, a resolution health support worker with Teechuktl Mental Health who assists former residential school and day school students, has heard of at least two children who were buried in the 1930s under the McCoy Lake bridge, near where the Alberni school operated for almost a century.

“The people that buried them are gone now,” said Watts. “They were kids that were forced to do it.”

For years Watts has heard stories of burial sites around the Alberni school, citing a 1996 study from the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council that calls for investigations into the circumstances of the deaths at AIRS and other residential schools.

The last few months have been hard for residential school survivors once news broke of the unmarked graves.

“It’s like they peeled back the scab,” observed Watts. “People were trying to heal, moving on with their lives. All of a sudden it got torn back again.”

Many outside of First Nations communities have been left to wonder how such a widespread injustice could happen in Canada. Besides committing $27 million in federal and $12 million in provincial funding to help with the investigations, Sept. 30 has been made a national holiday. Orange Shirt Day is now officially Truth and Reconciliation Day in commemoration of former residential school students.

“We have advised provincial public-sector employers to honour this day and in recognition of the obligations in the vast majority of collective agreements,” reads a joint statement from B.C.’s Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation Murray Rankin and Selina Robinson, minister of Finance. “Many public services will remain open but may be operating at reduced levels. However, most schools, post-secondary institutions, some health sector workplaces, and Crown corporations will be closed.”

Amid this government recognition of what former students have known for their whole lives, Watts cautions that healing will take a very long time.

“It’s not a one-time cash deal that’s going to solve everything,” he said. “It’s an ongoing thing that’s going to last several generations down the road.”

Meanwhile the discoveries of burials at former residential school sites continue to trigger those who spent their childhood at the institutions, causing them to re-experience things they were too young to comprehend. The real challenge continues to be how to leave such experiences in the past.

“We can hold on to stuff and let it eat us up, or we can realise what it is, let it go and move on,” explained Watts.

While contemplating this struggle the Tseshaht member recounts a story that comes to mind.

“There’s two wolves in your stomach. They’re always fighting. One represents love, happiness and all those things that are good. The other guy: hate, animosity, anger,” Watts recalled. “Which one is winning? The one you feed the most.”

After his adult battles with heavy drinking and drug abuse, Bernard Jack is working on his own healing, currently living in a treatment facility in Calgary.

“I’ve learned to pray in my own way, not kneel down and call, ‘Our father who art in heaven’,” he said, thinking of those who have shown him compassion as he works on his health. “It doesn’t always have to be your uncle, auntie, cousin or niece. It can be outside, you don’t have to push all of that public away.”

“’There are people here that care and love you, Bernie,’ I started to think,” continued Jack. “I just have to learn how to accept it. I’ve built up so many shells, armour around myself that it’s hard to get out now.”