Warning: The following article contains subject matter related to child abuse and addiction, and may be triggering to some readers.

Attending residential school caused children to emotionally shut down inside, part of a survival tactic that resulted in years of silence about their experience at the assimilationist institutions.

This is what Jennifer Wood has experienced and observed, who is a unit lead for commemoration projects and community relations with the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. With some other staff from the NCTR, she ventured from Winnipeg to be part of Port Alberni’s event marking the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. On Sept. 30 hundreds walked through Port Alberni to a gathering hosted by Tseshaht on the former site of the Alberni Indian Residential School, which shut down in 1973 after operating in various forms on the Tseshaht reserve since 1893.

“I know about Port Alberni and I know it was one of the worst schools in Canada,” said Wood, who is Ojibway from Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation.

Like her five siblings, parents and grandparents, she went residential school, attending the Portage Indian Residence in Manitoba.

“A lot of survivors won’t talk about it because they weren’t asked what they thought about anything,” she said. “You’re conditioned not to talk, you’re conditioned not to give your opinion on anything.”

But the experiences one endures during childhood remain, albeit hidden within the passing years. Stories end up re-emerging, something Wood’s sister Vivian experienced as an adult while undergoing a medical procedure that revealed a mark on her head. Her memory returned to when she was six.

“She peed the bed, and the nun made her strip the sheets,” said Wood. “She said, ‘You stand there until I come back.’ Well, the nun didn’t come back.”

Standing in the dark, Vivian fell down, fracturing her head on the bed. Without getting any medical attention, she healed, but the mark remained.

“It wasn’t until 40 years later, she had to get a CAT scan or something on her head, and the doctor asked her, ‘What happened to your head?’,” continued Wood. “Instantly she remembered.”

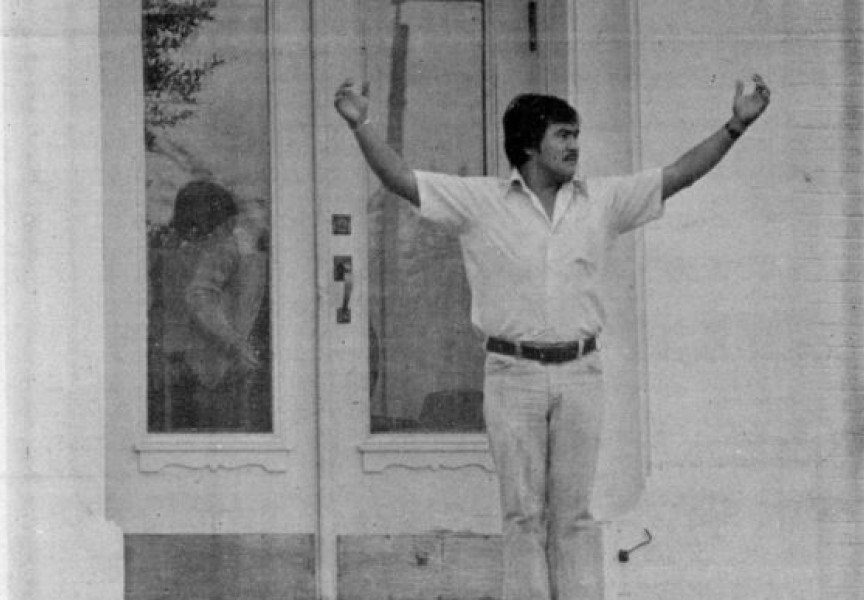

During the Tseshaht gathering Dolly McRae, a Gitxsan member who attended AIRS, asked residential school survivors to join her before the crowd, sharing their childhood stories of when they were away from family for so many years.

Tom Watts attended AIRS for four years.

“I learned a lot of things: I learned how to lie, how to steal, how to be hungry. They taught me how to hate my parents,” recounted the Tseshaht elder. “I used to walk up the hill there picking fern roots to eat, looking in the garbage cans for food.”

Watts saw children trying to hang themselves in the “miserable place”, although there was one positive element to the experience.

“All we did all day was play sports, sports, sports. So everybody who came out of this residential school were good athletes,” said Watts, who played on the senior A Alberni Athletics basketball team, winning a national championship in 1965.

Nora Martin of Tla-o-qui-aht also went to AIRS with her brothers and sisters, although she never got to see them while at the institution.

“When we were here there was a little boy, I never knew what his name was. He hung himself in that building over there,” she said, pointing at once was Caldwell Hall, a former student residence and one of the two structures from the residential school that still stands. “There was a lot of abuse at this school, there was a lot of neglect.”

Martin said her brother found the boy hanging. He became an alcoholic and refused to live with anyone, said Martin of her brother.

Many former residential school students have struggled with addiction, which becomes an emotional refuge amid the trauma, explained Wood.

“That’s the only thing that made them feel warm and comfortable,” she said. “When you’re shut down emotionally, you’re not growing, your brain isn’t growing. That’s why you face all these challenges when you go out of school.”

Huu-ay-aht member Ben Clappis attended AIRS from 1963-71. He knows about the boy found hanging in Caldwell Hall.

“That was my wife’s youngest brother, Mitchell,” he said.

After years of silence, Clappis found himself finally opening up about his childhood experiences at the institution as he was part of a court case that delved into child abuse at AIRS.

“I got brave enough to speak after all those years I was silent,” said Clappis, who now helps others in their healing with his role at the Kackaamin Family Development Centre. “I was abused in this school. I was sexually abused.”

Grace Frank attended AIRS and Christie residential school. She stepped inside the old Caldwell Hall building a few weeks ago to climb the stairs, but had to turn around and leave, as memories returned.

“I’ve had people tell me to get over it and let it go. How do you let it go when you’ve been traumatized for your whole life?” she asked, addressing he crowd. “For all the years that I tried to commit suicide, I’m so glad that I’m here today. I have five kids that I love very much.”

Frank is grateful that Tseshaht plans to demolish the old Caldwell Hall building, and is inviting AIRS survivors to participate in the tearing down process. Tseshaht Chief Councillor Ken Watts says the federal government has committed to fund this demolition, and that the First Nation plans to replace Maht Mahs gym, the other remaining AIRS building, with another facility.

“Our communities are struggling right now,” said Watts. “The best way for us to heal as a people is to do exactly what we’re doing today.”

“We need teachers to support us and make us feel good,” said residential school survivor Clara Clappis, who is 66. “My voice was taken away, and I’m just finding my voice now.”