Eight years into a public health emergency, fatal drug overdoses are declining, bringing encouraging news to the many people affected by British Columbia’s opioid crisis.

At the current rate of over six fatalities a day, poisoning from illicit drug use continues to be the leading cause of death for B.C. residents under 60, surpassing car crashes, homicide, suicide and natural disease combined. But recent data from the B.C. Coroners Service shows some decline to the crisis’ disturbing statistics. The Coroners Service reports that 192 people fell to illicit drugs in July - a 15 per cent decrease from the same month last year. The Coroner states that “expedited toxicological testing” detected fentanyl in almost nine out of 10 of these tragedies. Up until the end of July 1,365 people in B.C. have died by overdose, but each month of 2024 has shown a decrease from the same periods in 2023. Last year was the deadliest for B.C.’s opioid crisis with 2,572 fatalities.

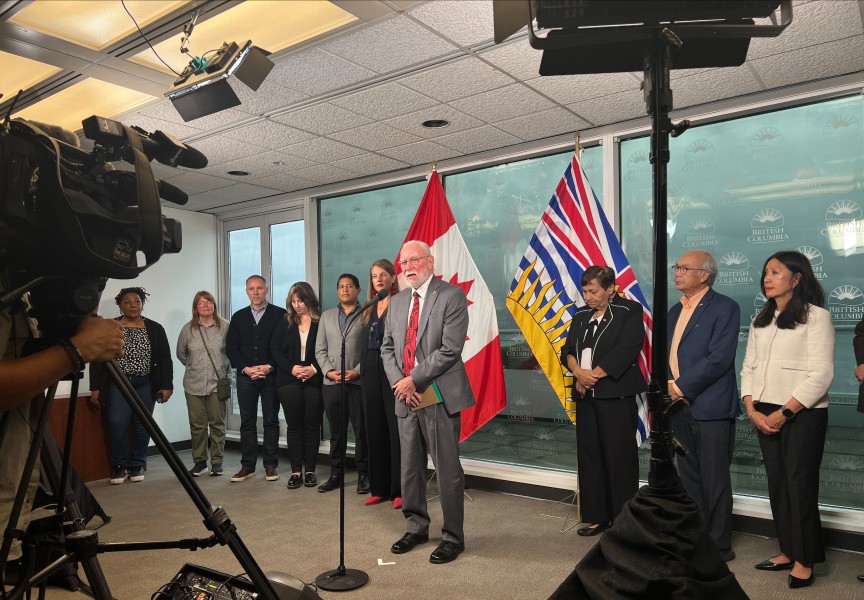

These most recent numbers came out Friday, Aug. 30, on the eve of International Overdose Awareness Day. An hour after the statistics were released that morning Brandy Lauder, chief councillor of the Hupacasath First Nation, addressed the crisis to an audience at the Best Western Barclay Hotel in Port Alberni.

“How we deal with it reflects on us as communities, as townships, countries, provinces. For the longest time, I think, Canada has been one of the failing ones,” she said. “They haven’t initialized the whole program, they only take what they think they can afford, and watch it fail.”

Indigenous people have been disproportionately affected by the crisis, with a fatality rate last year that was six times that the rest of B.C., reports the First Nations Health Authority.

In recent years substance use has become a foremost concern for Nuu-chah-nulth families as well.

“When your family member becomes addicted, you become the kind of person that has to save yourself, save the things you love, and what’s still remaining,” said Lauder, who stressed the importance of showing support to those in the grip of drug addiction - despite the difficulties of dealing with a loved one in such a situation. “We may have to back away a little bit to protect ourselves, but that does not mean we have to shut down and leave them out on the streets cold and addicted.”

‘I want to get sober’

Earlier in August the FNHA emphasized the toll the drug crisis has had on overall health outcomes for First Nations people in B.C. Dr. Nel Wieman, the FNHA’s chief medical officer, said that continuing fatalities in the drug crisis are a “major driver” in the decline of First Nations’ life expectancy, which fell from 73.3 years in 2017 to 67.2 in 2021, according to an interim report by the FNHA and the Office of the Provincial Health Officer.

“Because a big part of the life expectancy data is tied into deaths related to the unregulated extremely dangerous toxic drug supply in this province, we have to do something about that,” she said. “These are not throwaway people. This is not a segment of society that we shouldn’t care about or that we’re not even a part of or connected to.”

“Their whole brain becomes rewired to their next fix. They can go without food, they can go without shoes, they can go without a bed to sleep, because the only thing that’s programmed in their head is their next fix,” continued Lauder. “All they’re trying to do is survive and run away from the pain that they’re experiencing every moment of the day. They need the tools in order to figure out how to heal themselves, and the only tool they have is addiction.”

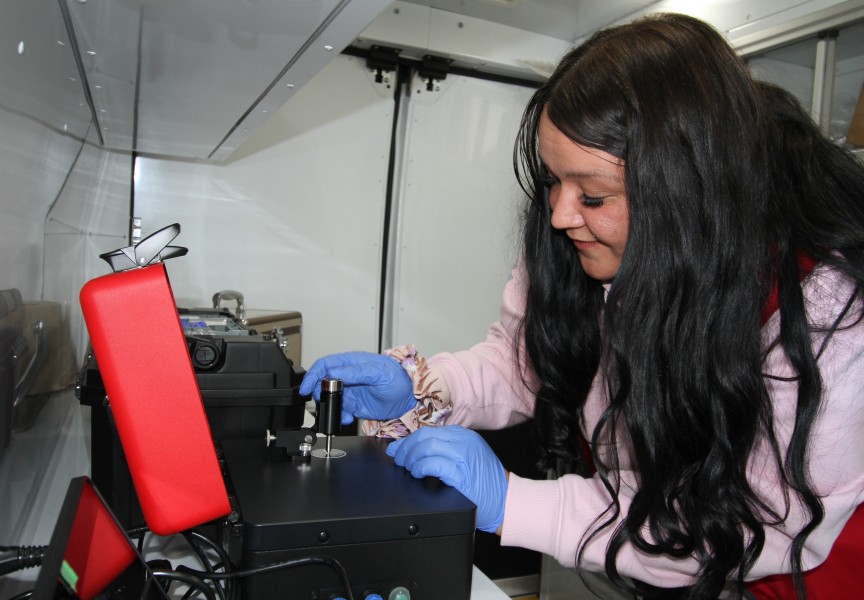

While Lauder and other elected representatives addressed an audience at the Barclay Hotel, further south in Port Alberni an event was held for people at the Overdose Prevention Site, a facility run by the Port Alberni Shelter Society on Third Avenue. It’s a busy place where Daniel Holland comes for support, as he awaits his chance to enter a recovery facility in two weeks. Holland has used crack for the past eight years, and the 51-year-old admits to first trying alcohol at the age of 8.

“My mom and dad used to always go to Hell’s Angels parties, they gave my first beer, my first cigarette, my first line of coke,” said Holland, who grew up in Richmond and is from the We Wai Kum First Nation. “You’re always chasing the dragon.”

Although he admits it’s hard being around illicit drug use at the Overdose Prevention Site, the support from staff there “levels out” his aggression. He had spent the preceding night in jail before coming to the OPS for lunch.

“I’ve got six kids and four grandkids. I try to be the best person that I can for them, but it takes over,” said Holland of his addiction. “I want to get sober.”

Mounting political scrutiny

Over the course of the public health emergency overdose prevention sites have been established across B.C. to mitigate the worst harms of the drug crisis. Do date, just one death has been reported at a supervised site in B.C., as these facilities serve as a fundamental example of the harm reduction approach to substance use. Harm reduction focuses on reducing the harms of addiction without requiring abstinence. It enables those who use to choose how they will manage their habits and health.

But this year this approach to managing substance use has faced political scrutiny. In August the Province of Ontario announced the closure of 10 supervised drug sites, due to new rules that prohibit them from operating within 200 metres of a school or daycare.

"Continuing to enable people to use drugs is not a pathway to treatment," said Ontario Health Minister Sylvia Jones.

This means Ontario will be closing almost half of its supervised substance-use sites – with no funding for additional locations to replace them. Instead, the central province has committed $378 million towards 19 new Homeless and Addiction Recovery Treatment Hubs.

It could be argued that British Columbia has led the way in harm reduction measures, as it became the country’s first province to decriminalize illicit drug use with a Health Canada exemption under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. In January 2023 this was announced as a measure to reduce the social stigma that substance users face – causing social scorn that discourages people from seeking help. But B.C. scaled back this approach in May by again prohibiting illicit drug use in public spaces and hospitals.

With an election approaching in October, criticism of the province’s decriminalization policy was mounting amid a leaked memo from a Northern Health supervisor, instructing staff to permit the open use and exchange of illicit drugs in hospitals – with the exception of smoking.

“While we are caring and compassionate for those struggling with addiction, we do not accept street disorder that makes communities feel unsafe,” stated Premier David Eby in a press release from May.

An infancy of treatment models

Harm reduction was never meant to be the solution to the toxic crisis – cautions Ron Merk, co-chair of the Port Alberni Community Action Team – only a means to keep people safe until individuals can find permanent solutions.

“The root causes are the issue. Harm reduction is a strategy that just helps us until we fix the root causes,” said Merk. “Until we figure out the solutions to those, and we have enough of them so that we can get 80 to 90 per cent of the people covered in them, we are faced with having these locations in our communities that are focused only on harm reduction.”

In many respects, the solutions being explored by health authorities are still in their early stages, an infancy of new treatment models that will undoubtedly require provincial policy reconsiderations in the future. In July Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry released a report recommending that the government more freely offer medical alternatives to illicit drugs at “compassion club”-like locations that don’t require a prescription. Her office noted that safer prescribed alternatives like Hydromorphone are only reaching a small fraction of the 165,000-225,000 people who use illicit drugs, as just an average of 4,777 prescriptions for medical alternatives were given for each month last year.

The province rejected this report.

“Addiction is a health issue and people struggling with addiction need access to the full continuum of services provided by our health-care system,” responded Jennifer Whiteside, minister of Mental Health and Addictions.

Meanwhile, Port Alberni has seen 150 fatalities since 2016, and with 38 deaths last year, the region was behind only Hope and Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside in its rate of lethal overdose.

The good news is this summer Island Health issued a request for proposals to bring a six-to-eight-bed “stabilization and supportive recovery” facility to the community. But far more is needed, stressed Mark.

“We’re not resourcing the recovery process so that the demand matches the resource,” he said. “As long as we have that disconnect, the only tool that we have left in the bag is harm reduction, keeping people alive until we actually figure that other portion out.”