A young Roosevelt elk is free roaming again after a female hiker tactfully disentangled an old parachute from around its neck and antlers.

The lucky bull Rosie elk was likely entwined in the strings and material from the parachute for a couple days, according to his rescuer who wishes to go unnamed.

“It’s about the animals and nature and human waste,” said the 39-year-old hiker.

“People should just pack their things out of nature. If it was a cutaway parachute, the person who cut their chute should have a GPS tracker and go retrieve it if it landed in nature because it causes stuff like this,” she continued.

Based out of Ucluelet, the hiker set out on Nov. 3 for a day in the Alberni Valley backcountry with her hound dog by her side. A trip plan was sent to a friend and she had her 10 hiking essentials on her back, including the GAIA GPS app for navigation as there is no cellphone reception in the area.

As someone who has hiked the southern half of the Appalachian Trail in the eastern U.S. and the entire Colorado Trail, plus 112 peaks on Vancouver Island, her 4.7-kilometre trek of choice was meant to be a relatively easy Sunday… until it wasn’t.

On the way up the mountain, she saw a group of trees violently shaking.

“I was very nervous. We tried to scoot far around whatever animal was there. We made some noise. We made sure whatever was there knew we were there and kept moving far around,” she said.

On the way back down about an hour later, she noticed the same group of trees still shaking.

“Normally animals don’t like to be around humans, and they will vacate when they hear a human in the area. They will never stick around, so I thought it was really odd that a large animal in the exact location was still making a ruckus.”

While still skirting around the shaking trees, she managed to get a glimpse of the animal and saw that it was an elk – not a bear.

“Thank God. But it’s a bull elk in rutting season, which is also incredibly dangerous. Coming from Alberta, that’s something that is drilled into your head as kid that elk are dangerous, stay away especially in the fall.”

With bear tracks circling the area, the hiker was curious to see why the elk was not able to move, so she latched her dog to a tree a safe distance away and crept in for a closer look.

“The cordage was wrapped around the antlers, around the neck, around the face and then around the trees. This elk had been jumping from side to side trying to shake lose, getting worse entangled. Underneath was a pure mud pit from it stomping and trying to move the whole time,” she said. “It was bad, my choices were walk away and leave the animal die, or attempt to free it…”

She took out her Leatherman multi-tool and started cutting wire cable that was on the trees far enough away from the elk and started talking to the elk saying, “Hey buddy, I’m just here to help you Mr. Elk.”

She put her hand out so the elk could smell her and made sure that the elk could see her.

“The elk actually kneeled down on all four, directly in front of me. At this point, I figured it was calm and allowing me to do this.”

It took her about 25 minutes to saw enough cord and material to set the elk free.

“At the end, I looked at the elk and said, ‘Pull.’ He just stood up and looked up at me for a second and then turned around and walked into the forest.”

She called her mom as soon as she got back into cell reception and reported the incident to B.C. Conservation and Search and Rescue the following day.

“I could have died. I know that. I knew it was dangerous. It let me help it. It must have been absolutely exhausted from struggling for days,” said the Ucluelet-based hiker while drinking a can of Lucky beer with a taco lunch at West Coast Shapes.

Named for Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th president of the United States (1901-1909), the Roosevelt elk, or ƛ̓uunim in Nuu-chah-nulth language, is Vancouver Island’s largest land animal, weighing over 1,000 pounds.

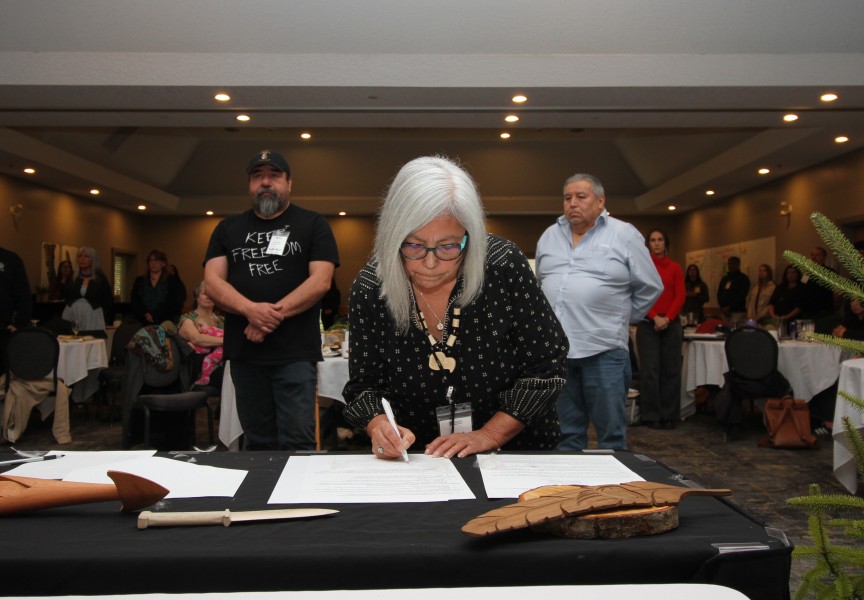

Roosevelt elk are a traditional food source for coastal First Nations. During pre-European contact, elk provided food, clothing as well as weapons and tools fashioned from elk antlers. Today, First Nations on Vancouver Island harvest elk on their traditional territories for meat and ceremonial purposes.

The Roosevelt elk is considered a species of special concern and remains on the Provincial Blue List after being on the brink of extinction due to over hunting and the expansion of human settlements during the gold rush of the mid-1800s.

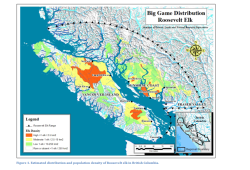

Nowadays, B.C. elk herds are experiencing an overall population increase in B.C., according to a 2015 B.C. government report, largely due to successful management practices that involved capturing elk and transporting them to priority sites.

In 1986, the estimated population of the Roosevelt elk in B.C. was 2,550. By 2014, the elk population in the province had increased to 6,900, according to the report.

“The increase is most evident in the South Coast Region where translocated populations are increasing rapidly,” states the elk management report.

Demand for hunting Roosevelt elk is high – about 15,000 B.C. hunters applied to hunt the majestic creature and about 300 Limited Entry Hunting permits were granted via the lottery system, notes the report.