Deferrals continue to promise temporary protection of old growth in the Fairy Creek watershed, but aggressive opposition remains to the prospect of any future logging in the area with a recent report of tree spiking.

On Jan. 29 B.C.’s Ministry of Forests announced another extension to defer logging around Fairy Creek, a highly contested valley of old growth north of Port Renfrew. Considered to be one of Vancouver Island’s few remaining watersheds untouched by industrial logging, this latest measure will protect almost 1,200 hectares of forest until Sept. 30, 2026.

The Fairy Creek watershed is Crown land that falls under provincial forestry regulations, but is also entirely located within the territory of the Pacheedaht First Nation.

“These temporary protections will allow discussions on the long-term management of the Fairy Creek watershed to continue in partnership with Pacheedaht First Nation,” stated the Ministry of Forests in a press release. “This action is consistent with government's commitments to reconciliation and to protecting British Columbia's oldest and rarest forest ecosystems.”

On the same day that the deferral was announced, another message came from the Ministry of Forests reporting a historical practice that many consider a form of eco-terrorism.

"Last week, I was notified that there are reports of tree spiking in the Fairy Creek area of southern Vancouver Island,” said Minister of Forests Ravi Parmer in a statement.

Tree spiking is the practice of driving a metal rod or nail into a tree with the intention damaging a chainsaw when the stand is logged, or wrecking a machine when the timber is processed in a sawmill. Tree spiking first became widely known in the 1980s to disrupt logging operations, but many environmental groups have since condemned the practice due to its danger to forestry workers.

"Spiking a tree, or even attempting to, is a dangerous criminal activity that puts the health and safety of B.C.'s forestry workers at risk,” said Parmar. “These reports are incredibly alarming and I condemn this criminal behaviour.”

The matter has been reported to the Nanaimo RCMP for investigation. A recent Times Colonist article reported that the ministry was mailed a package with photos of spiked trees in January. The photos are undated with no indication of their location, but a note with the package stated they are from “friends of Fairy Creek”, according to the article.

In recent years Fairy Creek has attracted one of the largest movements of civil disobedience in Canadian history, a growing protest against old growth logging that brought nearly 1,200 arrests. In the summer of 2020 blockades were being erected to halt the construction of logging roads into the valley, where some ancient yellow and red cedar trees are believed to be over 1,000 years old. Coordinated by the Rainforest Flying Squad, a steady flow of food, provisions and volunteers supplied the blockades.

At stake was an estimated $20 million worth of timber, according to the Teal Jones Group, which holds forestry tenure over Fairy Creek and the surrounding area that comprises Tree Farm Licence 46. At the time, the TFL 46 management plan called to maintain an annual harvest of 367,363 cubic metres, over half of which was old growth. The management plan stated that this harvest level would be sustainable for 50 years.

But opposition to any logging in the Fairy Creek watershed grew, and by early 2021 a court injunction had been imposed against any interference to forestry in the area. By May the RCMP moved in, and a wave of arrests started, reaching 1,000 by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, First Nations in the region were watching yet another case of outsiders coming into their territory to determine what was to be done with the forest. As an assertion of jurisdictional authority over their Ḥahahuułi, in June 2021 the Pacheedaht, Ditidaht and Huu-ay-aht released the Hišuk ma c̕awak Declaration. This called for the immediate halting of old growth logging into the Fairy Creek watershed until the First Nations assembled their own forest stewardship plans. The valley has remained protected ever since.

“While this essential work is being carried out, we expect everyone to allow forestry operations approved by our nations and the government of British Columbia in other parts of our territories to continue without interruption,” the nations said in a statement. “Please respect that our citizens have a constitutionally protected right to benefit economically from our lands, waters, and resources.”

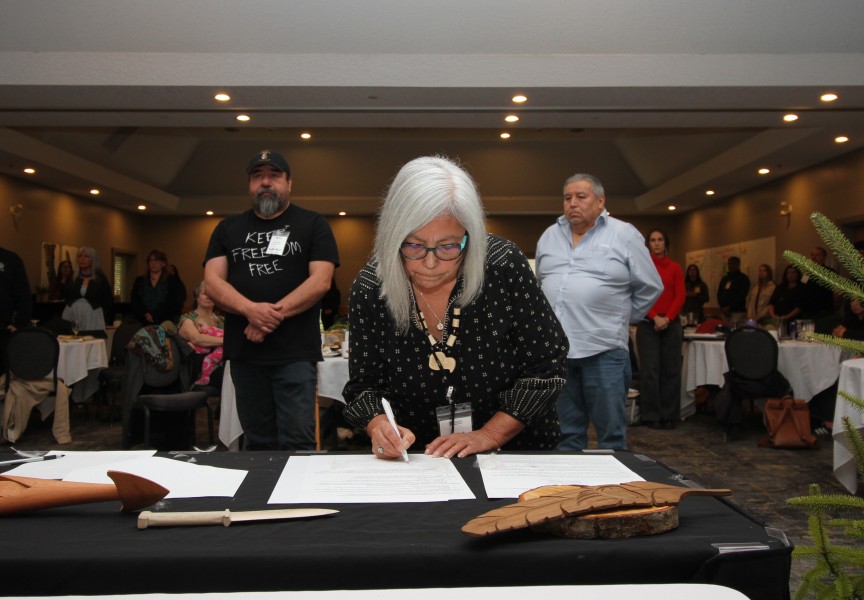

Pacheedaht’s Integrated Forestry Management Plan protects approximately 80 per cent of the Fairy Creek watershed, according to Chief Councillor Jeff Jones in an interview with Ha-Shilth-Sa in 2022. Like the Huu-ay-aht and Ditidaht, the Pacheedaht have explored a larger role in the forestry industry to generate economic activity for its community. The First Nation jointly owns Pacheedaht Anderson Timber Holdings, which has forestry licences in TFL 61 and operates a sawmill in Port Renfrew. In the past Pacheedaht has purchased timber from Teal Jones’ operations in the First Nation’s territory, and in October 2022 a memorandum of understanding was signed with the company. This agreement speaks of protections for old growth while finding economic opportunities for the company and the First Nation.

The province’s approach to forestry appears to be in a period of transition. While announcing the Fairy Creek deferrals on Jan. 29 the ministry referenced how it continues to be guided by an old growth strategic review first commissioned by the province in 2020. A follow up report released in May 2024 pledges to “fundamentally change the way that we view and manage our land and resources”.

“The voice of our forests is growing louder and more urgent, calling out past practices in managing the land and issuing warnings about the impacts of the climate crisis,” stated the From Review to Action report. “There are stark signals, like catastrophic wildfire, and more subtle ones, like the decline of western red cedar across coastal B.C.”