The 100-year-long fight to bring home the sacred Yuquot Whaler's Shrine from a New York museum is several steps closer, the director of the Land of Maquinna Cultural Society has said.

This year marks a century since the American Museum of Natural History purchased the ancient collection of ceremonial carvings and human skulls from two individuals for $500 in 1913, and removed it surreptitiously while their Nuu-chah-nulth village was away for whaling season the next year.

But despite the museum's continuing refusal to repatriate the ancient artifacts–apparently awaiting proper storage requirements in the community–Margaretta James told Ha-Shilth-Sa that Mowachaht/Muchalaht Nation has completed a “conceptual plan” for a future interpretive centre to house the shrine in Friendly Cove (Yuquot), and has even put young band members through education to manage, curate and preserve the collection upon its return, through a training program at North Island College.

James hopes to take several of the students to see the artifacts in New York in the coming months, the first time community members will have visited it since the 1990s, when James and several leaders visited its basement home.

But with $20 million still needed to build the centre, and federal talks ongoing, James is calling on the government to “step up to the plate” and fund the project so the shrine can be repatriated.

“Building an interpretive centre has always been one of our goals,” James said. “We have a conceptual plan of what this building will look like.

“Our elders said we need to acknowledge the traditional values of our people; we need the building to have these things intertwined. The Yuquot Whalers' Shrine is one important aspect of the spirituality of our nation... It is going to come back, and it is going to come back to Yuqout.”

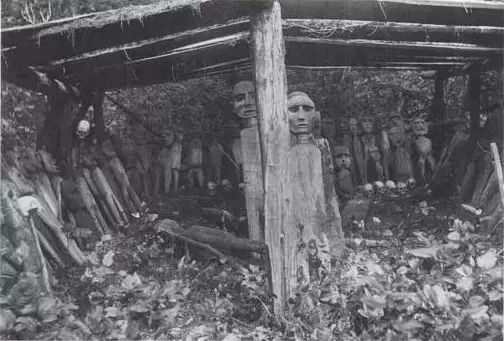

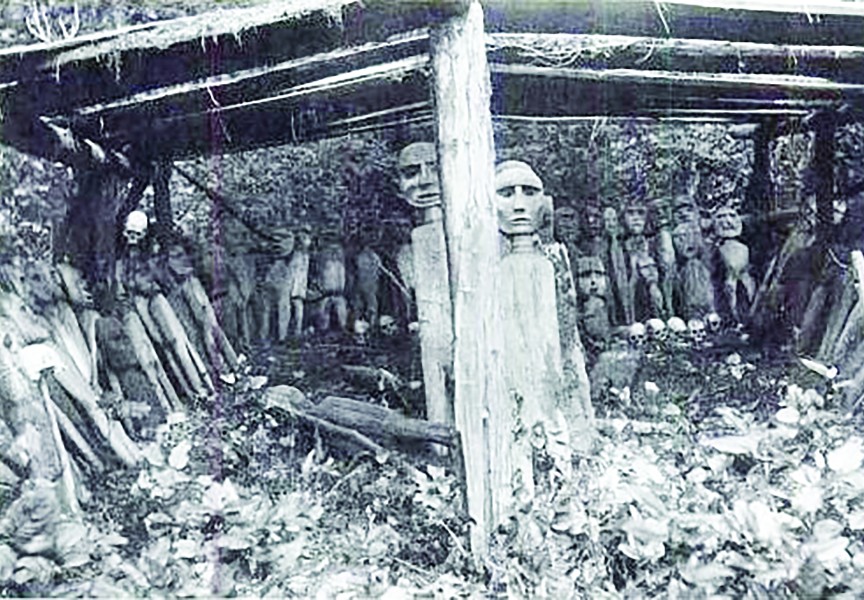

Also known as the Whaler's Washing House, the shrine's 88-large wooden human figures, 16 skulls and four whale carvings was originally housed in a five- by six-metre building at Yuquot, but was only accessible to the chief whaler in the community for spiritual purification before a hunt.

Despite the demise of traditional whaling, the community believes the shrine maintains its spiritual powers. Those powers, said a curator at the University of British Columbia's Museum of Anthropology, remain of vital importance in Nuu-chah-nulth culture.

“They're powerful works,” said Bill McLennan, a curator at the University of British Columbia's Museum of Anthropology. “They were in the past, but they still maintain that power. It's ethereal; they have an amazing presence.”

Twenty years ago, McLennan was tasked with photographing the sizeable collection in New York City, to gauge how much original paint remained on the carvings. But seeing the artifacts in museum storage, he recalled, did not do justice to the whole shrine – at least compared to early photographs of the original collection in Yuquot.

“The photograph in its whole assemblage is way more powerful than it sitting on racks and shelves,” he said, adding that it is up to the Mowachaht/Muchalaht community to decide whether a visitors’ centre or in its original outdoor location is the best way to display it if it ever returns.

“That discussion has been there for a very long time about repatriating it,” he added. “And if it does come back, where does it come back to? ... The community may want it as resource, but it won't be exactly the same thing it was before – but a record of their history on their own territory.”

James described her earlier visit to the undisplayed artifacts in the American Museum of Natural History as “one of those hair-raising back-of-your-neck experiences.”

“You could just feel the power of it,” she recalled. “Several of our chiefs were also taken to the museum in New York to see the shrine; it was even more powerful for them, because they know what the shrine was used for, and how important it was to the community and the families. The power of the shrine – you experience one of those moments you can barely describe.”

This year is not only the 100-year anniversary of the shrine's controversial sale. This November will also mark exactly 30 years since the federal government declared the now heavily forested original location of the Yuquot shrine–on the south end of an island within Jewitt Lake–to be a National Historic Site.

According to oral tradition, for thousands of years shrines like this one were maintained in secret locations by whaling families in Yuquot, who used them for cleansing rituals involving carved figures of spirits and animals, and sometimes human skeletons and remains. The shrine currently housed in New York belonged to the village chief, who was the only person allowed to approach or enter.