With diabetes statistics being what they are for Aboriginal Canadians, it is no surprise that there are dozens of Nuu-chah-nulth people living with the chronic disease.

Diabetes Canada reports age-standardized rates for diabetes are 17.2 per cent among First Nations people living on reserve and 10.3 per cent for those living off reserve. The rate for all Canadians is 9.3 per cent, according to data from 2015.

Diabetes Canada states that the country’s Indigenous peoples are among the highest-risk populations for the disease and related complications. Even worse, Indigenous people are being diagnosed and an increasingly younger age; they have greater severity at diagnosis than other populations, develop higher rates of complications and experience poorer treatment outcomes.

Diabetes is a disease in which the body’s ability to produce or respond to the hormone insulin is impaired, resulting in abnormal metabolism of carbohydrates and elevated levels of glucose (sugar) in the blood and urine. Diabetes leads to high blood sugar levels, which can damage organs, blood vessels and nerves.

About 10 per cent of people with diabetes have Type 1, which generally shows up in childhood and requires insulin. The other 90 percent have Type 2 diabetes which can, depending on the severity, be managed through physical activity and meal planning, or may also require medications and/or insulin to control blood sugar more effectively.

Diabetes Canada recommends that screening for diabetes among Indigenous people be carried out earlier and at more frequent intervals.

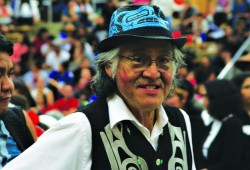

Ahousaht elder Wally Samuel, now in his 70s, was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes more than a decade ago. He has been prescribed Metformin to control his blood sugar and other medications to control side the side effects of diabetes. That includes medication to control his blood pressure and something to protect his stomach. His pharmacist meets with him regularly to go over his medications and to explain what they are for.

Samuel says he is on a daily medication regimen, taking some pills in the morning and again in the evening.

“It’s important to stick to your medication schedule,” said Samuel, adding that if he misses a dose he can feel his blood sugar levels rising or falling. “Low blood sugar isn’t good for you either.”

The toughest problem he faces is all the sugary treats served up at meetings and gatherings.

“There’s chumus all around,” he laughed.

Wally’s wife Donna helps him with his diet and reminds him to make more healthy food choices – take the fresh fruit, not the donut. “And I don’t pig out as much,” he laughed.

Samuel also stays active. “Just keep moving, you don’t have to be an athlete,” he advised.

He tests his blood sugar daily and listens to advice from the NTC nursing department, including Matilda Atleo, Community Health Promotion Worker.

“She has a display that shows all the sugar in pop; that is a real eye opener,” said Samuel, who quit drinking sugary drinks.

His word of advice is to remind caterers at events that there should be healthy snack options for diabetics.

Samuel said he used to be embarrassed that he had diabetes; that he felt too young to have it.

“But you can get it at any age,” he said, remembering a young father who carried insulin around for his child. For that reason, Samuel thinks it is important to start teaching young children about healthy eating.

A Nuu-chah-nulth woman in her 60s was also diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes about a decade ago. She spoke about her experience on the condition that her name is not revealed.

“I was at work one day when I felt a taste of sweetness that seemed to coat my mouth,” she told Ha-Shilth-Sa.

She has diabetes on both sides of her family so she wasn’t surprised when her family doctor tested her and diagnosed Type 2. She was immediately prescribed Metformin.

She advises people to take doctors’ warnings seriously, adding she never changed her eating habits because she feels fine. She doesn’t need to test her sugar levels at home and instead goes to the hospital for quarterly blood tests.

“One thing that bugs me is people assume you get diabetes from eating too much sugar or from obesity; it’s insulting,” she said.

She knows that Aboriginal people are among the highest risk population for developing diabetes.

“My doctor explained that diabetes happens when your pancreas can no longer process sugar properly,” she added.

She takes her prescribed medication twice daily and has had little trouble with blood sugar spikes, saying it has only happened to her a couple of times. She noticed after having a particular sugary drink she could feel the effects of her blood sugar rising.

“It’s what I would imagine it would feel like to be drugged,” she said.

She needs to eat every few hours to keep her blood sugar from dropping too low and she’s pleased that she lost 30 pounds recently.

She advises people to take advantage of free diabetes screening services, to talk to their doctors and to do their research.

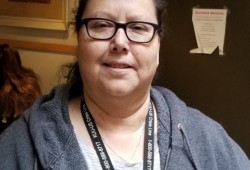

Gina Pearson, 56, said she was told by her doctor two years ago that she has prediabetes. She was advised to change her eating habits and get some exercise. But she didn’t take the advice seriously – why? Because she felt fine.

In the summer of 2018 she began feeling light-headed, fatigued, and dehydrated.

“I just wanted to sleep,” she said.

At first she thought she was suffering from depression and went to see her doctor. She was sent for blood and urine tests. She was also sent to a cardiologist for a pre-existing heart condition. After two minutes on a treadmill she was exhausted.

Her cardiologist advised her to start walking, to build up her fitness; and to watch her diet.

Shortly afterward she was called back to the doctor’s office about her test results. She heard the alarming news that her blood sugar was at 17.5. Normal blood sugar is in the four-to-eight range.

“I was 250 pounds at that time and I drank a lot of pop,” she said.

She was prescribed Metformin and given a home blood sugar monitor, which she was required to use daily.

“I was told to go back in a month; but when I did, my blood sugar hadn’t gone down,” she said.

Her dose of Metformin was doubled for the second month of treatment. When Pearson was tested again, her blood sugar level dropped to seven and she had lost 20 pounds.

“The doctor was glad that I had listened,” she said.

Pearson has given up sugary soda for the diet version, on the rare occasion she has pop. She drinks more water. She uses artificial sweetener for her coffee and honey for her tea. She has reduced the amount of potatoes and rice she normally ate and opts for vegetables.

Pearson admits that holidays are hard with all the food and treats around. She started a new hobby of making sugar-free snacks.

She goes for walks, takes part in fitness activities at the Port Alberni Friendship Centre and when she can’t get out, she dances at home with her granddaughter.

Her sacrifices are showing in her latest blood sugar reading of 4.6.

“The doctor told me that if my progress continues I will be taken off of the medication and will no longer be a diabetic,” she said with a bright smile.

She echoes the advice of others, that it is important to teach children about the importance of healthy food choices.